Pure and whole, tough and tender. Home. Alive.

An essay and conversation between Gretchen Frances Bennett and Laura Sullivan Cassidy

I first met Laura Sullivan Cassidy on a rainy night, sheltering in the doorway of the El Capitan building, home to the Seattle art venue, Vignettes. Our conversation, I believe, started with the weather. We were there to see Mel Carter’s “When the Caustic Cools,” projected on a building across the street, and we talked about the rain letting up.

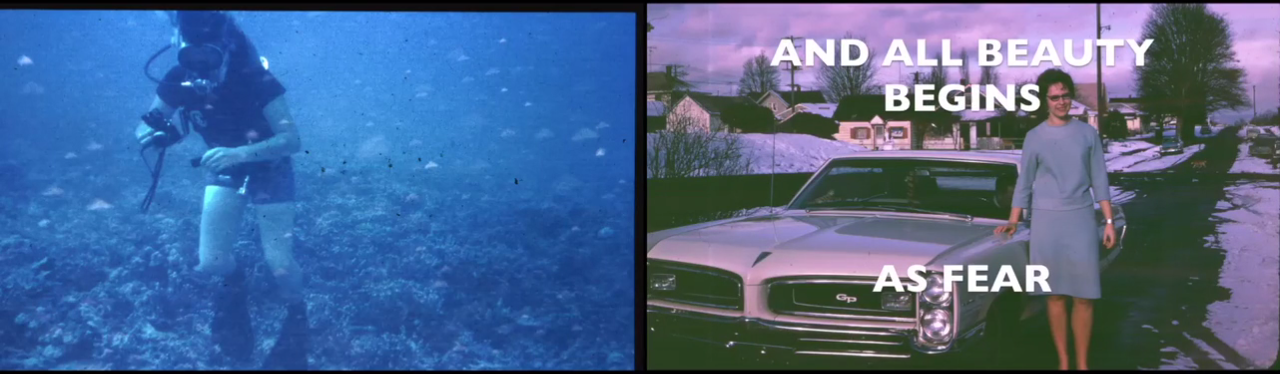

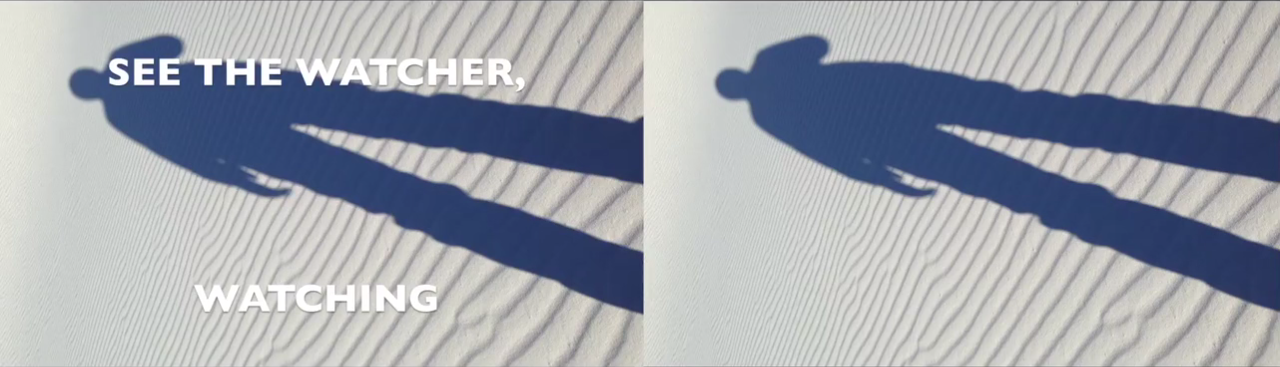

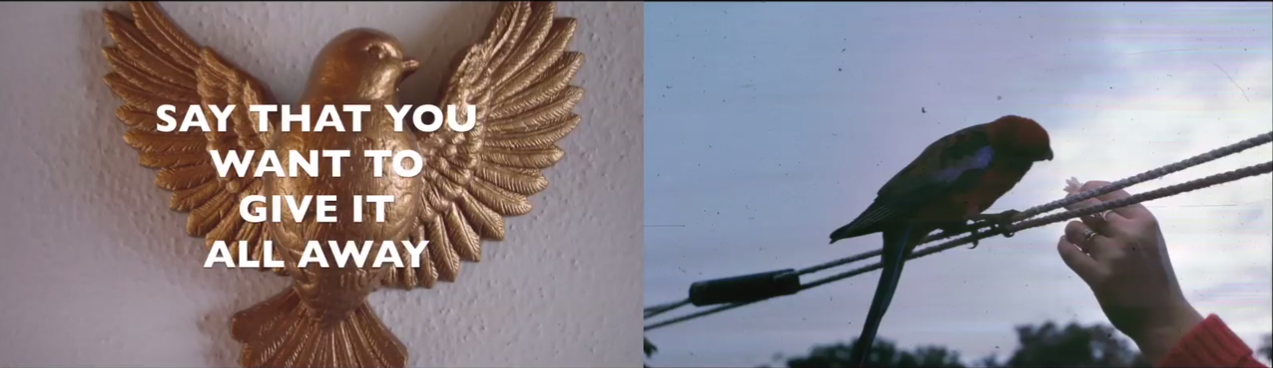

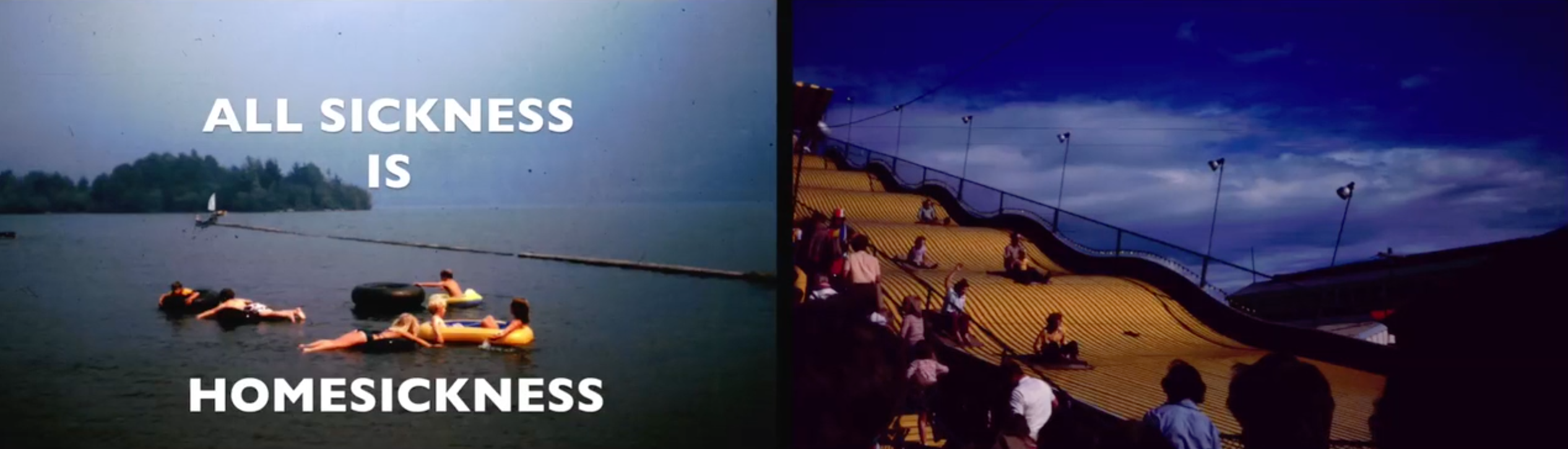

We met next on another wet night, when Vignettes Marquee presented Laura’s work, “What Feels Most True: A Dream Hypnosis for Radical Awakeness,” a two-channel projection of “found and collected family slides and digital images,” accompanied by a dreamy abstract audio track by Laura’s husband, Erin Sullivan. For this one–night–only presentation in a storefront in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, images cycled in slide show cadence, sometimes superimposed with san-serif text: “Three / Two / One / Before you can begin you must open your eyes / See the tattooed tear drops / See the watcher watching / See the knower not knowing a thing / Now, with your left hand, smooth the wrinkle that will not iron out / And with your right hand: feel / Can you feel warmth in what you’ve forgotten? / Can you feel pretty when you fall? / Then, say that we will find a way to reach each other / Say that you did not dream of airplanes falling from the sky last night / Say that you have not been having that dream for as long as you can remember / Say that you know nothing / Say that you have nothing / Say that you want to give it all away / Because what could feel more real? / What could be more true? / All sickness is homesickness / All hypnosis is self-hypnosis.”

Laura describes this work as being “somewhere between performance and persuasion… images like strobe lights and words like wands are meant to rearrange natives, immigrants, and passersby alike. The quasi-narrative, two-channel, glass-enclosed slideshow will reimagine the villagers; remember them, forget them, and return them…back to where they were when they started so long ago: Pure and whole, tough and tender. Home. Alive.” A promotional image for “What Feels Most True” is titled simply “Found Family Image, Kodachrome Slide.” This image, depicting kids floating on deep blue water under a slightly less deep blue sky, is both strange and known, like most photographs in this work. We see weedy gravel in front of white industrial garage doors, a hand feeding a bird, sea life, twin moveable jet bridges leading to no airplanes, side by side statues with caution tape necklaces, all brined souvenirs of absent animals, plants, dirt, watery nights, and stars.

We met next at her house, and talked about being ourselves, being tied to the weather, how we weren’t sleeping, and about our fathers, both scientists who passed away and left us image collections. We ate kale and listened to Henry Flint’s Raga Electric on vinyl. Later, Laura sent phone photos of her father, Paul M. Cassidy’s dive journals, pulling out phrases, like “Nothing really unusual,” and “Much too turbid.” “There were specific crabs my dad was studying in the Philippines. He told me he found a species no one knew about, he tacked the name ‘Paul’son’ there on the end, you can see it on the cover (of a dive journal)”. “I’ve understood much more about my need to notate and document, since going through his things. What a diarist!”

As I get to know her, I take any occasion to talk with Laura Sullivan Cassidy: in person, in weather, by text, or, in this case, by email.

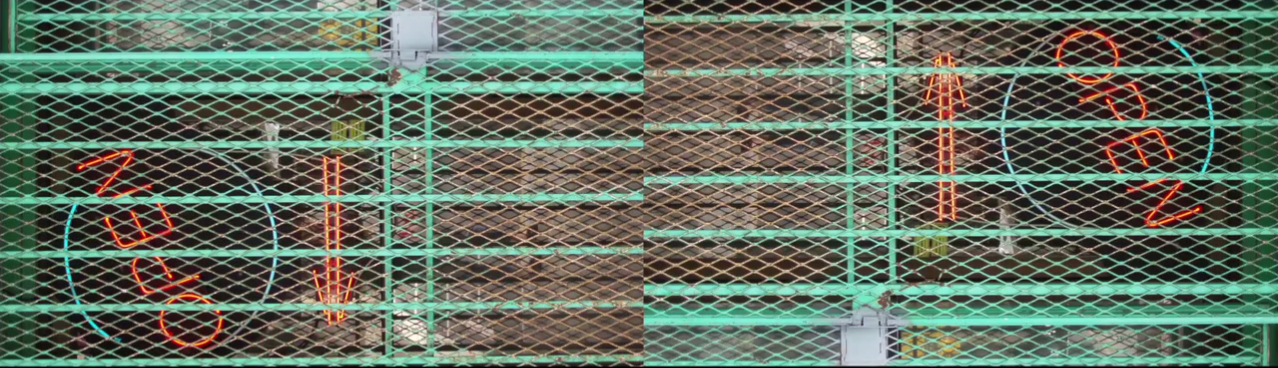

Gretchen Bennett: I saw an electric window sign in the International District, signaling both open and closed, when unlit. I thought of it, with your work. Do you look at the family slides as both open and closed spaces, and do they provide clues to your past and to your father; and, something that stops and can’t fully show itself?

Laura Sullivan Cassidy: Absolutely. I probably wouldn’t have used those words—open and closed—but they’re perfect.

After my dad retired he took ownership of all the family photos and slides, and scanned them in. He gave us all copies, and I’ve always loved family photos so I’ve always had them at the ready and I’ve periodically gone down rabbit holes with them, but I really and truly binged on them after he passed away. When I go into the folders now (he separated them via era: ’60s, ’80s, etc.), it’s as if the lights are on and the door is open but no one’s home. I can get in and look around, but there’s really no one who can answer my questions or show me around.

So yes, open and closed.

GB: I have a collection of Kodachrome slides from my father. When I rediscovered them, I had less a memory of the imagery, and more a memory of him taking them. Are images from our lives something we want, but we may need to forget about for a while?

LSC: That feels right. I somehow want it to be more right with the old Kodachrome stuff, but it may be most true with our iPhones. Most of us do this capture, capture, capture thing, and I suspect we really don’t even know why we’re documenting the sunset shadows or the dinner party or the art show or the cat sleeping. It’s reflexive at this point, but it can prove useful, too. How often do we say, “Oh I forgot all about this picture!” when scrolling through our handheld archives? My mind tends to be really busy all the time and I’m always mentally juggling, so I am forever finding things I have forgotten about. Images, notebook pages, groceries even!

Maybe we don’t need a cure from/for them, but gaps, keeping us separate from them, are good? So, when we realize (again?) that they are, it’s like more life?

I feel myself trying to name what that pay-off is. Are they more like life, is that what the reward is? I think for me, because my memory is sort of foggy and spotty, the reward is the opportunity to piece it all back together. The opportunity to tell or retell a story.

Some images provoke a visceral response and you’re back in that moment instantly, but some are more slippery than that, and that’s okay with me. I kind of like not knowing. I kind of like the soft, vague tether—and I’m really grateful for that. My memory has been weird ever since this medical event I went through a few years ago, and I wouldn’t have predicted that I’d be okay with the fog, but I really am. Images do sometimes clear things up, but for every image that offers clarity, there’s another that is impossible to place, name, tag, number, or hold on to.

GB: “The quasi-narrative, two-channel, glass-enclosed slideshow will reimagine the villagers; remember them, forget them, and return them…back to where they were when they started so long ago.” It seems that they are returned to a new home each time, given the looping course of the images, I find that exciting. “And I’ll be there with them—making those return/transformations, too.”

Isn’t this a way of moving forward, saying both hello and good-bye, letting go pieces at a time, as if through “strobe lights?” Not to forget, exactly, but to remember, like talking and listening at the same time, so that every moment is a living moment, and this living is not separate from the imagery, but on it, like dust and fingerprints.

LSC: Absolutely, the goal really was to create a bit of a mind-scramble. I truly meant it as a hypnosis or a meditation; a way to wipe the screen and get rid of some negativity and replace it with some wonderment and remembrances and curiosity.

GB: Are these found photographs also remembering and forgetting in front of us?

LSC: I seem to want to hang on to them as not quite fiction and not quite non-fiction, so I suppose they are remembering and misremembering.

It’s like how we all have different memories of any one event, right? Especially because film (as opposed to digital) forces and allows us to capture and retain a lot of imperfect, in-between moments, I feel like what the old pictures do is lob little moments at us and those moments aren’t true or untrue. They aren’t giving us back that day in 1979 and they aren’t taking it away. Like an argument in the matriarch’s living room about which uncle owned the white Pontiac station wagon, they are saying, “Hey look, the past isn’t something you can hold on to.”

And I guess I want that to also be a reminder that you can’t hold on to the present or the future either. None of this is completely knowable. Not all of this is nameable. Ten people in any given room, on any given street corner, see ten different things. Is it weird that I find that comforting?

GB: Not weird, at all. I see your work as elemental — the everyday we all know. But I also think the work is biased towards your particular sensibilities. Not only with “What Feels Most True,” but I’m thinking now of a line from Mountain Lakes, from your recent book Backyard Birds Barking at Planes: “Never has our greed been so pure and so right. Never has it been so difficult to leave a place, never has it felt this cruel.” When I read this, I can see the lake the whole time. Everyone can easily reference their own version of a lake, and its transformative qualities.

From The Phone Call, also from Backyard Birds, is the limpid sentence, “Before all of this and any of you.” Here, I see a part of a life lived, a pause, and more life will be lived, in some sequence, like a slideshow.

LSC: I love that my stories can feel like a slideshow, and yes, what moves me the most are the incidental days when being human is kind of frozen in ice for minutes at a time, and then—poof—it thaws again.

I think where I have found my own place in writing, both fiction writing and in journalism, is in those particulars. I do take in a great deal. Retaining it? Depends whether I write it down or not. But I take in a great deal. I see a lot of what’s happening in shadowy corners and I hear things in pauses and stops and starts. I am not saying that those things are absolute truths, but what I pick up often really resonates. I have experience and confidence enough to admit that. I notice things, and I’m proud of that. And grateful for it.

GB: “What Feels Most True” seems to be as engaged with literature and performance, as it is with art. Do you relate to your work as a visual artist, more, or as a writer, and does this matter, for the work?

LSC: I have always identified very, very strongly and clearly as a writer but for the past ten years or so I’ve been very driven to do anything other than hand you a page of words and ask you to read it. While I’m certainly very interested in publishing, I’m equally interested in finding new and different ways to tell you a story.

In many ways, my roots are in music, so I have this weird and persistent metaphor about putting out a record or setting up a show at a club. I want to be able to do the equivalent of that within the literary realm. I think once I came to really good terms with the fact that my short stories are indeed really quite short, and that my fiction is more kinda-true than not-true, I felt even more motivated to do, well, to do weird stuff with my work. To do ‘other’ stuff with it.

I do a lot of visual stuff too, though. It’s true. I also really like collaborating with visual artists. I like illustrating my stories and I’m not sure I’ve ever put any of them out in the world without some kind of visual accompaniment.

GB: For me, “What Feels Most True” relates to Jonas Mekas’ documentary film As I was Moving Ahead, Occasionally I saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty, and how he compiled his home movies into a film, in the order the rolls came off the shelf, saying, “I have never been able, really, to figure out where my life begins, and where it ends.” Is this how you work?

LSC: Actually, I think I’m a writer because I’m trying to understand life. I don’t think it’s definitively possible, but I want to try. I want to put some of it down in a certain way that feels true enough. Like, I can accept this rendering of what happened, or what could have happened. Or what happened through this one particular lens. I am highly, highly motivated to understand things, but in a perhaps confusing way, I don’t have a death-grip on that understanding. It just feels good for a little while to feel like I have some resonating ideas about why and how.

But like all art and literature, once I pass the thing to you, you get to decide how you understand it. It’s a cool contrast with my life as a journalist. In that role, I want you to know for sure what I’m trying to tell you. But when I’m writing freely from the world around me, separate from work, I want to just decode this little thing I saw or felt or heard or did, and then I want you to hold on to it for a little while and decode it too. It’s a telephone game.

GB: Because you are not always the person who took the photographs, is meaning up for grabs; do you become free to assign meaning, based on what you know of the photographer, who is, in many cases, your father?

LSC: As far as I know, my dad took all the vintage images. There were some current/contemporary digital images in there as well, and those came what was dumped into laptop folders from a couple of digital cameras that Erin and I have shared over the years.

But in terms of the old images, the meaning is so up for grabs. Again, it’s a telephone game. That image of people riding flour sacks down the wavy yellow slide, god, I really have no idea. I think it’s out by the ocean somewhere. Like, we probably rode go carts immediately before or after.

What did my dad think he was remembering with that shutter button? I have no idea. Maybe he took the picture out of obligation or as a distraction; maybe he was thinking about work or his sore back or what he didn’t get to do as a poor Irish catholic kid in Tacoma.

But when I take that photo and layer some ideas on it, and give it to you, that one moment in my dad’s life is alive again. Ideally at least, it’s reactivated and it can do new and different things with whatever you layer onto it.

I wanted to take some of those old moments, and some less old moments, and put them back into the world—together with the reminder that we can trust ourselves and we can love ourselves and we can be ourselves. We HAVE to trust and love and be ourselves—mostly because if we don’t, it’s impossible to trust and love and be with others. It’s like that thing in planes: put your own oxygen mask on first, then help those around you.

I need to get my oxygen mask on right now, and my way of getting that flow going again is to remember who I am and what I am came here to do.

Laura screened Agnes Varda’s documentary film, “The Gleaners and I” in in her home, as a good-bye event for Vignettes founder, Sierra Stinson, moving to New York. In a “much too turbid” state of sleeplessness, I couldn’t attend, but I’ve seen this film multiple times. It follows gleaners, as they forage for food, and it points to itself, a film of images gathered and compiled by a woman, like “What Feels Most True.” An online essay on “Gleaners” by Homay King states that digital media disembodies and frees the referent from its frame, while “Gleaners” rematerializes the digital, by hooking it back into time and passing seasons. “Now, with your left hand, smooth the wrinkle that will not iron out / And with your right hand: feel.” Varda pauses to film one aging hand with the other.

Lifeforms of “What Feels Most True” are freed from their frames, and it is these depicted forms—a crab pincher, a woman—not their square matrices, that route themselves through our consciousness. At the end of “Gleaners,” Varda visits The Museum of Villefranche, and the painting that may have inspired her film. Edmond Hédouin’s “Gleaners Fleeing the Storm” is brought outside into bad weather. “To see them in broad daylight with stormy gusts lashing the canvas was true delight.” Her focus isn’t on the painting itself, but on the women running home with their wheat. And the wind kicks up.

Back to Articles