Dead People Never Stop Talking

Q&A with Michelle Peñaloza and Eric John Olson

Images by Eric John Olson unless otherwise noted

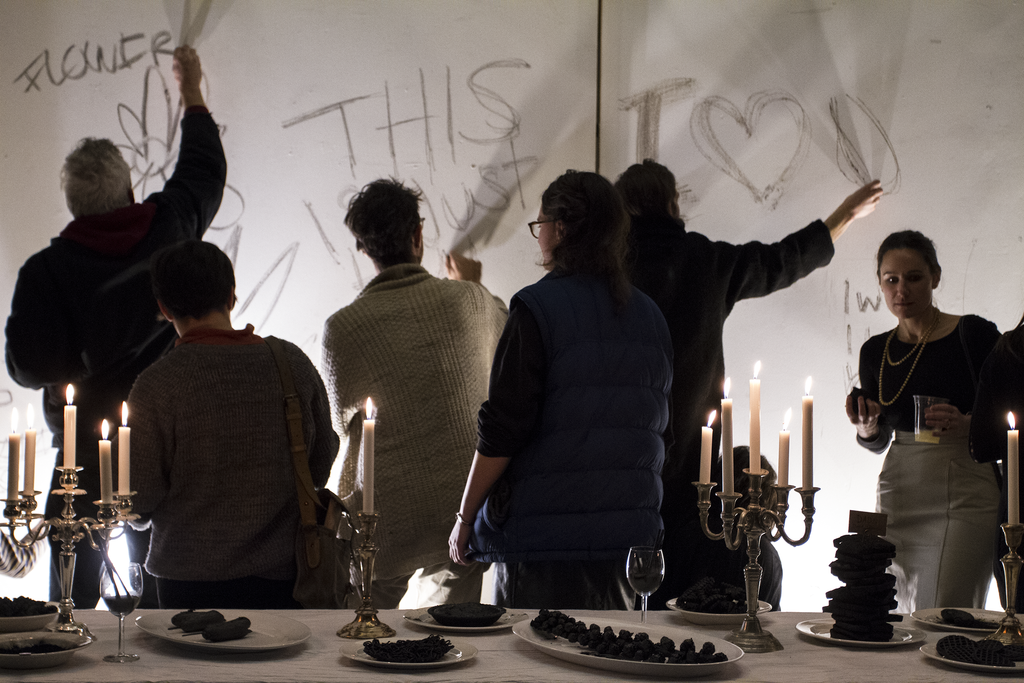

Image: James Harnois. We Are a Crowd of Others, exhibition by Gail Grinnell, Sam Wildman, and Eric John Olson

From September to December 2016, artists Gail Grinnell, Samuel Wildman, and Eric John Olson used their residency at MadArt Studio to weave together an expansive site-specific installation with a series of public programs that investigated the language and resonance of ordinary acts.

As beautifully written in her essay, “Author Redux: Neither Dead Nor Discourse”, Abigail Susik describes the site-specific installation:

“Artist Gail Grinnell constructs a massive site specific installation out of yards and yards of dyed spun polyester, the kind used for clothing patterns, in mimicry of the actions and movements embedded in her own mother’s sewing practice. After crafting achingly intricate cuttings in muted shades from the spun polyester, in meandering shapes that wander from swirls to skeletal patterns and back, Grinnell drapes the melancholy, lace-like lengths from hooks placed high on the industrial walls of MadArt. Grinnell’s son, the Portland-based artist Samuel Wildman, then gathers these fragile strips and incorporates them, on a continuing basis throughout the duration of the project and sometimes with his mother’s help, into a monumental funnel-shaped structure, reminiscent of a wasp nest, which swallows most of the gallery space. Next to this astounding entity, Wildman’s own sculptural assemblage, more intimately-scaled and made out of salvaged wood, liquid nails, and mason jars filled with concrete, ponderously accretes over time. Where Grinnell’s form emphasizes the forward-driving pulse of artistic production, the urge to expand, Wildman’s pinpoints on the other hand the halting precariousness of construction, the shyness of craft.”

Image: James Harnois, Installation by Gail Grinnell and Sam Wildman

The open forum of public programs gave the public, participants, conversants, poets, performers, and artists a space to interact and delve deeper into questions about how the past and future can haunt the present, making its way into our daily rituals. Projects included workshops for catastrophe preppers, public re-enactments of meals reminding people of their dead or dead-beat dads, screenings accompanied with science lectures, open rehearsals of a new dance by Tia Kramer and Tamin Totzke, and an exhibition of oral and visual histories of Seattle’s DIY music scene.

The following is a Q&A by poet Michelle Peñaloza with one of the artists, Eric John Olson, discussing the public dinner series.

Michelle Peñaloza : Where did the idea for the DEAD DAD DINING CLUB begin?

Eric John Olson : I wanted to create a way for people to talk about what absence means and how they hold it in their day-to-day lives. I was thinking about the ways in which we reenact people or do these small things that remind of us someone. They hold a memory of the loss and kind of act as a substitute for it. And then meals just seemed to fit in well. I was just thinking about recording people eating their dad’s favorite meal and talking to them about what it reminded them of, to have people all around a shared table and rendering that as a video installation.

When I was invited to contribute to the MadArt [“MA”] project, I talked to Sam and Gail about what I was already working on with this project and since there was a kitchen at MA, Sam was like, “You should host live meals!” I had hosted a potluck version at SOIL, but these felt a lot more meaningful for everyone involved, creating a re-enactment of each meal.

MP : What are some of the things that people have done for the different dead dad dinners? Have they been very different?

EJO : To start off the series, I did one myself because I felt that it was only fair.

For it I made a table that was tilted, one that went back and forth for each person sitting at it. You had to balance the plate on the table while you were eating. I wanted to try to represent the balancing act of talking about loss and grief; I didn’t want to make it easy for people to eat.

Then at one end of the table was a TV playing my dad’s favorite TV shows because he really liked to watch TV while he ate.

Abyssinia, Dad, Eric John Olson,

MP : What were some of your dad’s favorite TV shows?

EJO : … Star Trek and M*A*S*H. So, at my dinner, I played a M*A*S*H episode, a really sad one, where one of the doctors finally gets to leave the war but his helicopter gets shot down on his way home… and on the other end of the table, I placed my grandfather’s rocking chair, which my dad inherited and then I inherited. For [my dad’s] birthday, we would always make a big dinner and he’d always want Yorkshire Pudding and say “I don’t want to eat at the dinner table because it’s my birthday, since it’s my birthday I want to eat it while relaxing in my rocking chair and watching T.V.” So I wanted to recreate that.

MP : In terms of other people who have participated, can you talk about the process from you asking them to participate, to the development of their ideas, and then their execution of the dinner?

EJO : With each person it was quite different. I usually asked them if there was anything they’d like to reenact, how they would want to cook the meal, how did they want to set up the space for people to eat, and what kind of conversations we would want to lead during the dinner.

People did a massive variety of things—Norah’s was a BBQ; we barbecued in the back of MA. She really wanted people to talk about their favorite things about dads and about their dads because she felt that ever since she lost her dad, whenever people asked about him and she said that he was dead, that the conversation would just immediately cut short, instead of—

MP : Instead of her learning about people’s dads—

EJO : Exactly. So there was a whole discussion about that.

For Anne’s meal, everyone went around the table and toasted someone they lost; it was set up like a more formal, candlelit dinner. The recipe was based off of the last meal that she made for her dad when he was dying; she had heard that the “last thing to go” was the sense of smell and so she made this Pasta Provençal with lots of rosemary and garlic. She shared a whole story about that memory on the back of the menus, and that was a tearjerker. People were crying and sharing. It was a really beautiful night.

MP : Timothy’s was really interesting. I thought that was really cool; it was a different way to think about a meal.

EJO : Yeah, and… then, for Timothy, what reminds him of his dad is burnt toast. And that’s because, as he talked about it during the [event], his memories of his dad are really memories that his mom would tell him about his dad and burnt toast represented the chaos in his family, of growing up without a dad, because he lost his dad so young, and kind of the instability that that created in his family. Whenever she would burn toast or some dish his mom would say “but, your dad loved burnt toast,” and he recollected the fact that she always tried to talk him into being like his dad… and so for him, it’s almost more about the stories that we hold and what they tell about the absence.

So he decided to take an entire meal and burnt it to a crisp—all of these different weird frozen foods that he would eat when he was a kid and that his dad would have loved: crinkle-cut fries, pot pies, corn dogs, hamburgers—then he asked people to use those things to write on a wall—what loss they are holding in their bodies.

Ashes to Ashes, Timothy Firth, 2016. Timothy burnt all the foods that reminded him of his dad.

Participants at Timothy’s meal were invited to write was loss they were holding on to a wall with the burnt food.

MP : Yeah, I loved the way [Timothy’s] went; I found it very meaningful.

EJO : I think your meal was actually one of my favorite meals and I think that you had the benefit of being the last person to do it. Also, you and I have collaborated before, so I feel like you were ready to be like, “Ok, let’s do a reenactment and let’s make this really meaningful”. It felt more like performance art than a straightforward dinner.

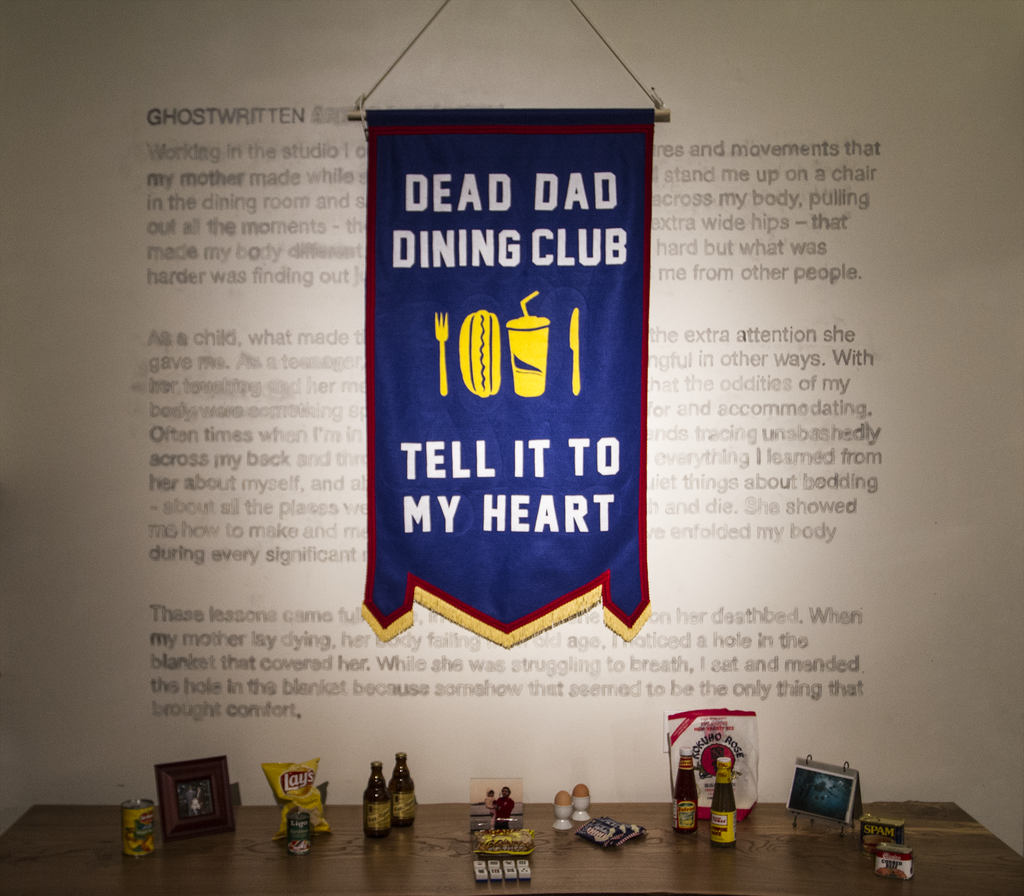

What I thought was really special about yours was the simple details of creating the space: putting tape on the ground to make parking spaces for people to sit side by side and reenact the idea of going to a drive-in and getting – y’know – chilli cheese dogs at Sonic like you did with your dad and drinking cherry limeades. The act of opening the bag and people unwrapping the fast food. Also, how you put stories of your dad in the bags so that people could go around and read aloud memories of your dad. Hearing those memories shared around the room really created a picture of who your dad was. And, then, how it ended, where everyone got up and danced to the Taylor Dayne song, “Tell It To My Heart”. The same song that was in the video we’d been playing all evening of you dancing with your dad as a child. That was really, really magical.

MP : Yeah, that was really awesome. I was really glad to have done it.

MP : So, why a dining club?

EJO : I’m really interested in encouraging conversations about difficult things, things that we don’t normally want to talk about or even acknowledge. I feel like art gives you a couple of tools to help address things like that. Beauty, humor, narrative are great anchors to bring people in and get them to open up. And so, for the DDDC I was thinking of it as a club because it is an actual unofficial club that none of us want to members of, but are members of. I wanted to highlight that everyone is bonded together over this kind of special handshake, silent wink of knowing what it’s like to have a deadbeat or dead dad. And understand what that loss is, and how we hold it in our lives. Then the other thing I was really interested in was trying to aestheticize it, without diminishing it? How to make it feel safe for people to come in and participate? I liked this idea of a club, and I was like, it would be fun if it was a stodgy, old stinky man’s club.

MP : We should have hats, like Shriners!

EJO : Yeah! I was going to make little pins, like letterman’s pins and I still might, but I was just thinking about those Elks club banners and those old Rotary Club banners and how there could be a Hall to commemorate the dead patriarchy or something. And so I was interested in playing off of that, and the old Norwegian church potlucks I went to as a child. I made one banner for the original potluck and people said they really loved it and so then I had this idea to make a banner for every meal… and Gail Grinnell was like, “you have to do it,”

Dead Dad Dining Club, felt banner, Eric John Olson, 2016. Memorial table set for Eric’s dinner.

MP : So, there is a Dead Dad Dinner Club banner for every meal?

EJO : Yeah, they’re all up at MadArt Studio right now. There’s one for every meal except one where the host didn’t want a banner made; I think it was too sad for her.

I really liked the idea of making an object that allowed people to imagine what the meal could have been like to go along with the story…

Image: James Harnois, Banners left to right for: Anne Blackburn, Michelle Peñaloza, Timothy Firth, Norah Kates, and Sara Lee Coleman with Rachel Ravitch.

MP : I think the banners really do that, I think especially Timothy’s and mine. I feel like my banner captures what my dinner was like.

EJO : I’m really interested in this idea, well, I guess it is part of being interested in social practice, right? What makes this series of meals different than any series of dinners? What makes this project different than just “I have a project that’s mine…”, whose sole authorship lies with the originating artist.

I think in doing things that are socially engaged, what makes them most meaningful is figuring out how to give agency to the people that you ask to participate; how you collaborate with them and make it feel really meaningful to all of the people involved. There’s a slippery slope in working with people and “using” people to make your artwork; it can be completely unethical or slide easily into something really uninteresting to me.. But, I’m really inspired by this balance of a cooperative practice and its potential for all participants. At the same time I don’t think good ethics alone makes a good artwork… and also there can be problems if you say everyone has the agency to do anything. You can get something that is very weird, sloppy and kindergarten-like…y’know?

MP : Yeah, there has to be a hand in curation—

EJO : Yeah, you start with this lens, this idea that you ask people to contribute to, but then each piece, they’ve authored. I’m there trying to help push them to think about it inside of a gallery space, to think about it in the context of a conversation… but, overall, I just tried to do everything I could to support those ideas, in hopes that the people who hosted the meals would be really invested in and feel agency and ownership in it. That to me is what makes the best project. It makes the best thing because we have created a space and a clear lens to examine these things that we are all holding on to and together we can shine a light on them and say they are important and that we should create more space for this type of work, this kind of therapy, you know, so… [mumbly] maybe I’m rambling, too much artspeak…

MP : Naw, you’re fine. This project is probably one of my favorite things that you’ve done. I think it’s an amazing project. How do you feel about it? Does it feel like that to you?

EJO : It feels good. I mean, I’m proud of it.

MP : You should be! I think it’s a really, really beautiful project. As a participant hosting one of the meals, one of the things I thought was an interesting experience for me was the meals being open to the public. Y’know, my father’s death, the loss of him, is such a hugely personal thing that. It ended up being amazing, but at first, I was just planning the meal and I didn’t really think about how there might be strangers there… And then they were there and I felt weird at first, but it was totally fine. And that, that’s very interesting to me too, because I had several people that I didn’t know at all come up to me after and say “Thank you so much for sharing your dad.” I feel like it was new and interesting and odd and good to introduce my dead father to strangers and really beautiful, too. I don’t know if it is like this for you, too, but I find one of the ways this loss hurts for me as I get older is the fact that people I love will never get to know my dad, you know? Like, my partner will never, can never know him.

EJO : Yeah but hold him with you, you keep him alive everyday. How do we share that without saying, “Oh, look at my photobook” and “Hold my grief and loss with me.”

MP : Yes. How do we make it about our dead—remembering and celebrating them—

and not about the pain we carrying in losing them.

Sonic Chili Cheese Dogs & Cherry Limeades, dinner by Michelle Peñaloza, 2016. Banner and memorial table for Michelle’s dad.

Chili cheese dog being eaten by participant at Michelle’s dinner.

Participants sit side by side in yellow tape designated parking spaces to reenact a Sonic Drive- In experience at Michelle’s dinner.

Back to Articles