An essay and conversation between Gretchen Frances Bennett and Laura Sullivan Cassidy

Pure and whole, tough and tender. Home. Alive.

I first met Laura Sullivan Cassidy on a rainy night, sheltering in the doorway of the El Capitan building, home to the Seattle art venue, Vignettes. Our conversation, I believe, started with the weather. We were there to see Mel Carter’s “When the Caustic Cools,” projected on a building across the street, and we talked about the rain letting up.

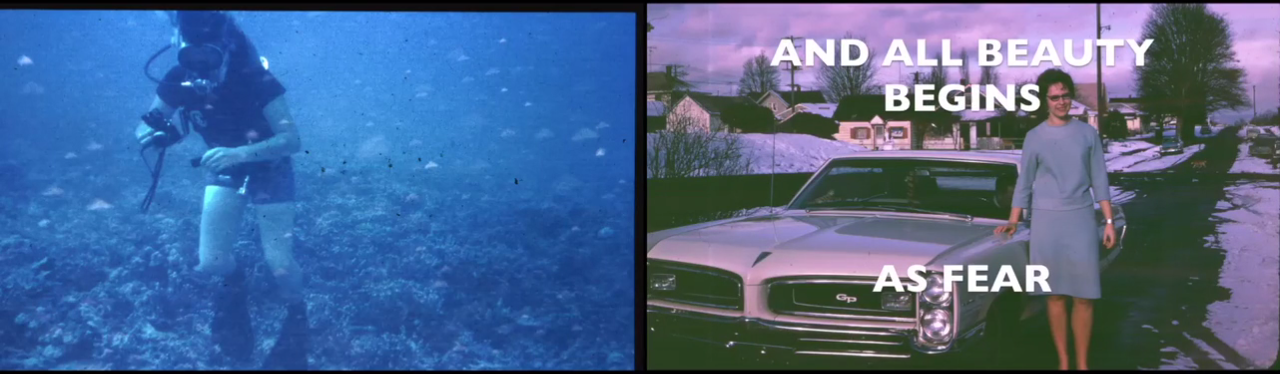

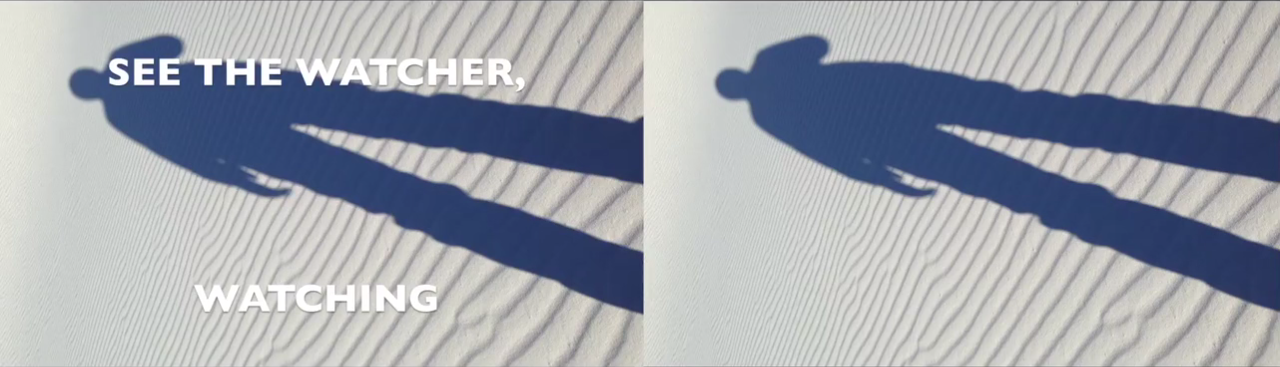

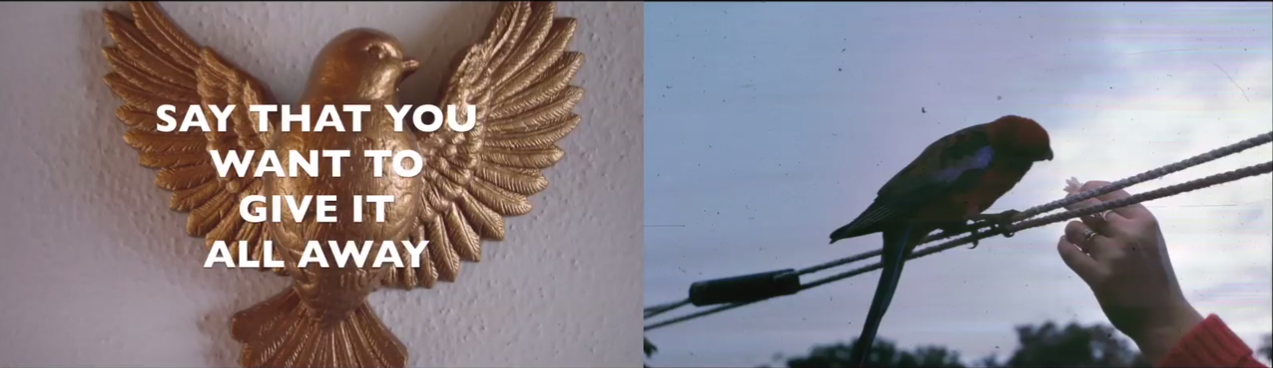

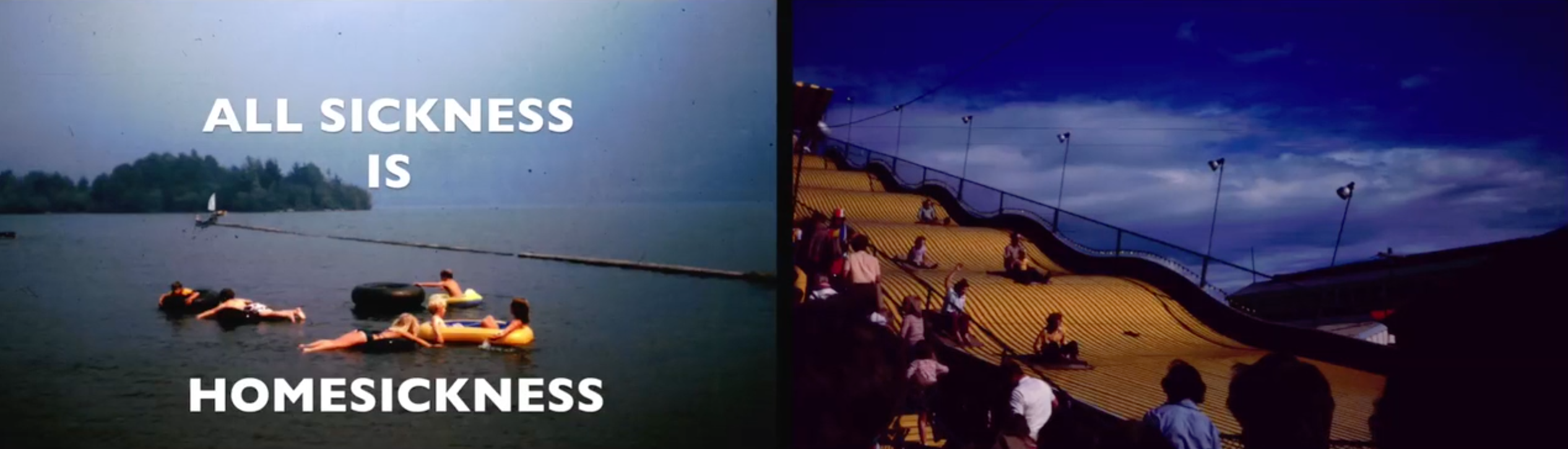

We met next on another wet night, when Vignettes Marquee presented Laura’s work, “What Feels Most True: A Dream Hypnosis for Radical Awakeness,” a two-channel projection of “found and collected family slides and digital images,” accompanied by a dreamy abstract audio track by Laura’s husband, Erin Sullivan. For this one–night–only presentation in a storefront in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, images cycled in slide show cadence, sometimes superimposed with san-serif text: “Three / Two / One / Before you can begin you must open your eyes / See the tattooed tear drops / See the watcher watching / See the knower not knowing a thing / Now, with your left hand, smooth the wrinkle that will not iron out / And with your right hand: feel / Can you feel warmth in what you’ve forgotten? / Can you feel pretty when you fall? / Then, say that we will find a way to reach each other / Say that you did not dream of airplanes falling from the sky last night / Say that you have not been having that dream for as long as you can remember / Say that you know nothing / Say that you have nothing / Say that you want to give it all away / Because what could feel more real? / What could be more true? / All sickness is homesickness / All hypnosis is self-hypnosis.”

Laura describes this work as being “somewhere between performance and persuasion… images like strobe lights and words like wands are meant to rearrange natives, immigrants, and passersby alike. The quasi-narrative, two-channel, glass-enclosed slideshow will reimagine the villagers; remember them, forget them, and return them…back to where they were when they started so long ago: Pure and whole, tough and tender. Home. Alive.” A promotional image for “What Feels Most True” is titled simply “Found Family Image, Kodachrome Slide.” This image, depicting kids floating on deep blue water under a slightly less deep blue sky, is both strange and known, like most photographs in this work. We see weedy gravel in front of white industrial garage doors, a hand feeding a bird, sea life, twin moveable jet bridges leading to no airplanes, side by side statues with caution tape necklaces, all brined souvenirs of absent animals, plants, dirt, watery nights, and stars.

We met next at her house, and talked about being ourselves, being tied to the weather, how we weren’t sleeping, and about our fathers, both scientists who passed away and left us image collections. We ate kale and listened to Henry Flint’s Raga Electric on vinyl. Later, Laura sent phone photos of her father, Paul M. Cassidy’s dive journals, pulling out phrases, like “Nothing really unusual,” and “Much too turbid.” “There were specific crabs my dad was studying in the Philippines. He told me he found a species no one knew about, he tacked the name ‘Paul’son’ there on the end, you can see it on the cover (of a dive journal)”. “I’ve understood much more about my need to notate and document, since going through his things. What a diarist!”

As I get to know her, I take any occasion to talk with Laura Sullivan Cassidy: in person, in weather, by text, or, in this case, by email.

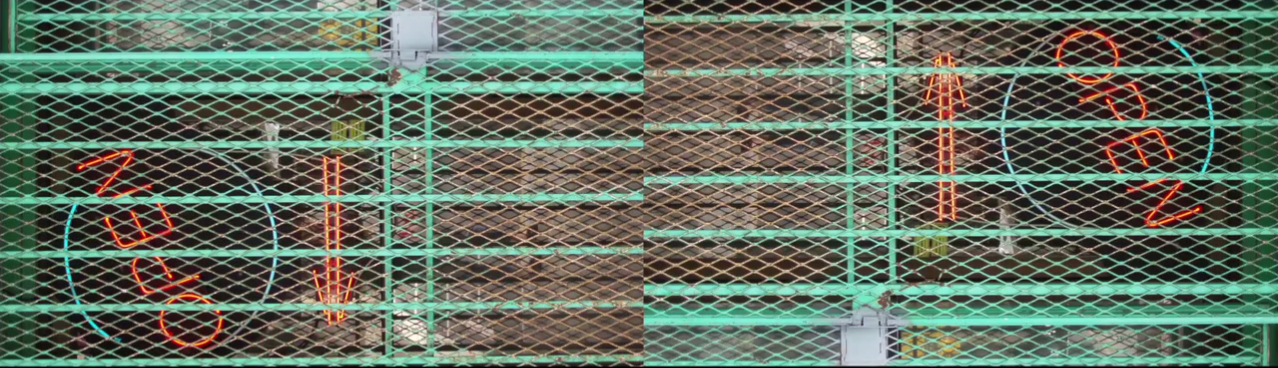

Gretchen Bennett: I saw an electric window sign in the International District, signaling both open and closed, when unlit. I thought of it, with your work. Do you look at the family slides as both open and closed spaces, and do they provide clues to your past and to your father; and, something that stops and can’t fully show itself?

Laura Sullivan Cassidy: Absolutely. I probably wouldn’t have used those words—open and closed—but they’re perfect.

After my dad retired he took ownership of all the family photos and slides, and scanned them in. He gave us all copies, and I’ve always loved family photos so I’ve always had them at the ready and I’ve periodically gone down rabbit holes with them, but I really and truly binged on them after he passed away. When I go into the folders now (he separated them via era: ’60s, ’80s, etc.), it’s as if the lights are on and the door is open but no one’s home. I can get in and look around, but there’s really no one who can answer my questions or show me around.

So yes, open and closed.

GB: I have a collection of Kodachrome slides from my father. When I rediscovered them, I had less a memory of the imagery, and more a memory of him taking them. Are images from our lives something we want, but we may need to forget about for a while?

LSC: That feels right. I somehow want it to be more right with the old Kodachrome stuff, but it may be most true with our iPhones. Most of us do this capture, capture, capture thing, and I suspect we really don’t even know why we’re documenting the sunset shadows or the dinner party or the art show or the cat sleeping. It’s reflexive at this point, but it can prove useful, too. How often do we say, “Oh I forgot all about this picture!” when scrolling through our handheld archives? My mind tends to be really busy all the time and I’m always mentally juggling, so I am forever finding things I have forgotten about. Images, notebook pages, groceries even!

Maybe we don’t need a cure from/for them, but gaps, keeping us separate from them, are good? So, when we realize (again?) that they are, it’s like more life?

I feel myself trying to name what that pay-off is. Are they more like life, is that what the reward is? I think for me, because my memory is sort of foggy and spotty, the reward is the opportunity to piece it all back together. The opportunity to tell or retell a story.

Some images provoke a visceral response and you’re back in that moment instantly, but some are more slippery than that, and that’s okay with me. I kind of like not knowing. I kind of like the soft, vague tether—and I’m really grateful for that. My memory has been weird ever since this medical event I went through a few years ago, and I wouldn’t have predicted that I’d be okay with the fog, but I really am. Images do sometimes clear things up, but for every image that offers clarity, there’s another that is impossible to place, name, tag, number, or hold on to.

GB: “The quasi-narrative, two-channel, glass-enclosed slideshow will reimagine the villagers; remember them, forget them, and return them…back to where they were when they started so long ago.” It seems that they are returned to a new home each time, given the looping course of the images, I find that exciting. “And I’ll be there with them—making those return/transformations, too.”

Isn’t this a way of moving forward, saying both hello and good-bye, letting go pieces at a time, as if through “strobe lights?” Not to forget, exactly, but to remember, like talking and listening at the same time, so that every moment is a living moment, and this living is not separate from the imagery, but on it, like dust and fingerprints.

LSC: Absolutely, the goal really was to create a bit of a mind-scramble. I truly meant it as a hypnosis or a meditation; a way to wipe the screen and get rid of some negativity and replace it with some wonderment and remembrances and curiosity.

GB: Are these found photographs also remembering and forgetting in front of us?

LSC: I seem to want to hang on to them as not quite fiction and not quite non-fiction, so I suppose they are remembering and misremembering.

It’s like how we all have different memories of any one event, right? Especially because film (as opposed to digital) forces and allows us to capture and retain a lot of imperfect, in-between moments, I feel like what the old pictures do is lob little moments at us and those moments aren’t true or untrue. They aren’t giving us back that day in 1979 and they aren’t taking it away. Like an argument in the matriarch’s living room about which uncle owned the white Pontiac station wagon, they are saying, “Hey look, the past isn’t something you can hold on to.”

And I guess I want that to also be a reminder that you can’t hold on to the present or the future either. None of this is completely knowable. Not all of this is nameable. Ten people in any given room, on any given street corner, see ten different things. Is it weird that I find that comforting?

GB: Not weird, at all. I see your work as elemental — the everyday we all know. But I also think the work is biased towards your particular sensibilities. Not only with “What Feels Most True,” but I’m thinking now of a line from Mountain Lakes, from your recent book Backyard Birds Barking at Planes: “Never has our greed been so pure and so right. Never has it been so difficult to leave a place, never has it felt this cruel.” When I read this, I can see the lake the whole time. Everyone can easily reference their own version of a lake, and its transformative qualities.

From The Phone Call, also from Backyard Birds, is the limpid sentence, “Before all of this and any of you.” Here, I see a part of a life lived, a pause, and more life will be lived, in some sequence, like a slideshow.

LSC: I love that my stories can feel like a slideshow, and yes, what moves me the most are the incidental days when being human is kind of frozen in ice for minutes at a time, and then—poof—it thaws again.

I think where I have found my own place in writing, both fiction writing and in journalism, is in those particulars. I do take in a great deal. Retaining it? Depends whether I write it down or not. But I take in a great deal. I see a lot of what’s happening in shadowy corners and I hear things in pauses and stops and starts. I am not saying that those things are absolute truths, but what I pick up often really resonates. I have experience and confidence enough to admit that. I notice things, and I’m proud of that. And grateful for it.

GB: “What Feels Most True” seems to be as engaged with literature and performance, as it is with art. Do you relate to your work as a visual artist, more, or as a writer, and does this matter, for the work?

LSC: I have always identified very, very strongly and clearly as a writer but for the past ten years or so I’ve been very driven to do anything other than hand you a page of words and ask you to read it. While I’m certainly very interested in publishing, I’m equally interested in finding new and different ways to tell you a story.

In many ways, my roots are in music, so I have this weird and persistent metaphor about putting out a record or setting up a show at a club. I want to be able to do the equivalent of that within the literary realm. I think once I came to really good terms with the fact that my short stories are indeed really quite short, and that my fiction is more kinda-true than not-true, I felt even more motivated to do, well, to do weird stuff with my work. To do ‘other’ stuff with it.

I do a lot of visual stuff too, though. It’s true. I also really like collaborating with visual artists. I like illustrating my stories and I’m not sure I’ve ever put any of them out in the world without some kind of visual accompaniment.

GB: For me, “What Feels Most True” relates to Jonas Mekas’ documentary film As I was Moving Ahead, Occasionally I saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty, and how he compiled his home movies into a film, in the order the rolls came off the shelf, saying, “I have never been able, really, to figure out where my life begins, and where it ends.” Is this how you work?

LSC: Actually, I think I’m a writer because I’m trying to understand life. I don’t think it’s definitively possible, but I want to try. I want to put some of it down in a certain way that feels true enough. Like, I can accept this rendering of what happened, or what could have happened. Or what happened through this one particular lens. I am highly, highly motivated to understand things, but in a perhaps confusing way, I don’t have a death-grip on that understanding. It just feels good for a little while to feel like I have some resonating ideas about why and how.

But like all art and literature, once I pass the thing to you, you get to decide how you understand it. It’s a cool contrast with my life as a journalist. In that role, I want you to know for sure what I’m trying to tell you. But when I’m writing freely from the world around me, separate from work, I want to just decode this little thing I saw or felt or heard or did, and then I want you to hold on to it for a little while and decode it too. It’s a telephone game.

GB: Because you are not always the person who took the photographs, is meaning up for grabs; do you become free to assign meaning, based on what you know of the photographer, who is, in many cases, your father?

LSC: As far as I know, my dad took all the vintage images. There were some current/contemporary digital images in there as well, and those came what was dumped into laptop folders from a couple of digital cameras that Erin and I have shared over the years.

But in terms of the old images, the meaning is so up for grabs. Again, it’s a telephone game. That image of people riding flour sacks down the wavy yellow slide, god, I really have no idea. I think it’s out by the ocean somewhere. Like, we probably rode go carts immediately before or after.

What did my dad think he was remembering with that shutter button? I have no idea. Maybe he took the picture out of obligation or as a distraction; maybe he was thinking about work or his sore back or what he didn’t get to do as a poor Irish catholic kid in Tacoma.

But when I take that photo and layer some ideas on it, and give it to you, that one moment in my dad’s life is alive again. Ideally at least, it’s reactivated and it can do new and different things with whatever you layer onto it.

I wanted to take some of those old moments, and some less old moments, and put them back into the world—together with the reminder that we can trust ourselves and we can love ourselves and we can be ourselves. We HAVE to trust and love and be ourselves—mostly because if we don’t, it’s impossible to trust and love and be with others. It’s like that thing in planes: put your own oxygen mask on first, then help those around you.

I need to get my oxygen mask on right now, and my way of getting that flow going again is to remember who I am and what I am came here to do.

Laura screened Agnes Varda’s documentary film, “The Gleaners and I” in in her home, as a good-bye event for Vignettes founder, Sierra Stinson, moving to New York. In a “much too turbid” state of sleeplessness, I couldn’t attend, but I’ve seen this film multiple times. It follows gleaners, as they forage for food, and it points to itself, a film of images gathered and compiled by a woman, like “What Feels Most True.” An online essay on “Gleaners” by Homay King states that digital media disembodies and frees the referent from its frame, while “Gleaners” rematerializes the digital, by hooking it back into time and passing seasons. “Now, with your left hand, smooth the wrinkle that will not iron out / And with your right hand: feel.” Varda pauses to film one aging hand with the other.

Lifeforms of “What Feels Most True” are freed from their frames, and it is these depicted forms—a crab pincher, a woman—not their square matrices, that route themselves through our consciousness. At the end of “Gleaners,” Varda visits The Museum of Villefranche, and the painting that may have inspired her film. Edmond Hédouin’s “Gleaners Fleeing the Storm” is brought outside into bad weather. “To see them in broad daylight with stormy gusts lashing the canvas was true delight.” Her focus isn’t on the painting itself, but on the women running home with their wheat. And the wind kicks up.

Coincidence of Molecules

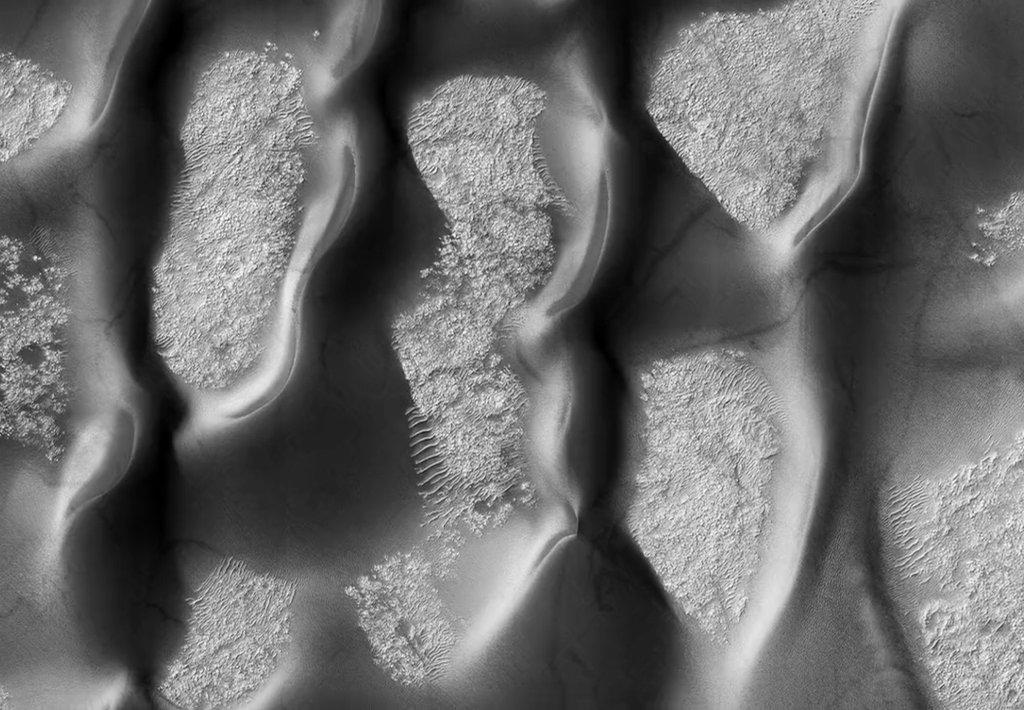

A conversation between Tessa Bolsover and Erin Elyse Burns

It’s a brisk winter evening – startlingly cold for Seattle. On a sidewalk in Capitol Hill, a group of people is huddled in front of an apartment building. There’s a quiet shuffle punctuating the crowd’s tempo – bodies shifting weight from one foot to the next, gently trying to ward off the chill. Just overhead are two windows filled with a video diptych that has a pace not unlike our own. Continuously moving over time, changing from image to image, and punctuated with evocative, fragmentary poetry. Tessa Bolsover’s Soon our bodies will be other buildings, on display at Vignettes’ Marquee exhibition series, calls upon environmental, molecular processes that evolve subtly. I have just returned to the Northwest after an intense stint in Nevada, saying goodbye to my mother, and feeling fairly certain I will not see her again. Grief is heavy on my mind. In Tessa’s project statement, she writes “In times of grief I turn to the idea of the body as a collection of materials. Our bodies exist for only a brief moment: a coincidence of molecules, soon to disseminate into countless other forms.” As I watch the video cycle through its patterned phases, I am struck by its lack of emotivity. A stick dragged across the snow. Deep sea divers swimming gracefully. Abstract macro imagery that looks like ice and snow through a microscope, yet I can’t help but see a pattern of human ears. Cells filmed through a microscope. A shadow falls upon a tree in birch forest. The camera enjoys the act of looking — the imagery inhabits real time. Through the lens of a biological perspective, I view beautiful imagery with a cool, scientific tone. I leave the night wondering if this is particular to me, or if Tessa has chosen an objective position as a strategy for the content of the work.

Erin Elyse Burns: The languorous imagery in Soon our bodies will be other buildings creates a certain calm that strikes me as reserved, almost without attachment. Will you speak to the emotional tone of your piece? Am I off in reading it as perhaps implementing the objectivity of a scientist?

Tessa Bolsover: I find a deep calm in the acknowledgement of the body as an entity within a large network. For me, observing becomes a kind of ritual to reintegrate with the strange and beautiful system of molecules of which my body is a part. I don’t see it as detachment as much as an attempt to empathize with the objectivity of the world beyond my ego.

Recently I’ve been reading a lot about the idea of Decreation (as re-defined in Anne Carson’s book of the same title), which basically means stripping away the self in order to get closer to the unknown (i.e. god). Observing the transience of materials is a way of stepping away from my mind and into my body, so to speak.

EEB: What lead you to utilize a looping imagery structure similar to the technique of phasing, as established by minimalist composers like Terry Riley and Steve Reich? Do you have a musical background?

TB: While working on this project I found the video editing process similar to the process of composing music. The concept of phasing had been floating around in my head for weeks, so utilizing an interpretation of the technique in my video looping process seemed like a natural fit. One of the main themes I was working with is the idea that molecules are constantly re-forming in various combinations, meaning that on a large scale, each object or entity can be reduced to a fleeting encounter between molecules, each following its own trajectory. Traditionally in phase music, two musicians simultaneously perform the same score at slightly different tempos, so that over time the relationship between the two players is realigned repeatedly, swaying between unison, echoing, and doubling. I wanted to extend this metaphor into my work by looping the two videos side by side at slightly different tempos so that the relationship between the two screens would change with each loop. Images and text fall in and out of unison periodically, putting the same emphasis on both order and disorder.

EEB: You work primarily in still photography – what has exploring the medium of video been like for you?

TB: I’m pretty new to making videos — it definitely had its share of challenges and opened up new ways of experimenting within time-based parameters, something I don’t usually get to do directly through my still photography.

EEB: You use both found footage and imagery you’ve captured – how do you approach this collage-like structure?

TB: Collage definitely feels like the right word for it. The footage I captured was a collection of gestures exploring the temporary physicality of my body within various landscapes. The rest of the imagery I collected through public domain archives online. Most of the videos I pulled from included little or no information on what the images were and why they were made — I found the combination of these sourceless videos and my own recordings an interesting juxtaposition and a way to contextualize the issue of interiority vs. exteriority.

EEB: Will you speak to the poetry you’ve written for this work?

TB: Writing is a huge part of my practice, although it rarely makes its way into my visual work. I wanted the text to feel like a collection of fragments, similar to the video segments. I was also thinking a lot about the way meaning is created through juxtaposition, and calling into question the extent to which we can read images like text and text like images.

soon our bodies will be other buildings excerpt, two channel video, 2017

Vignettes ‘Marquee’ installation excerpt / Seattle, Washington, February 2017

Three Freedoms

Josh Poehlein

March 17, 2017

Common AREA Maintenance

2125 2nd Ave

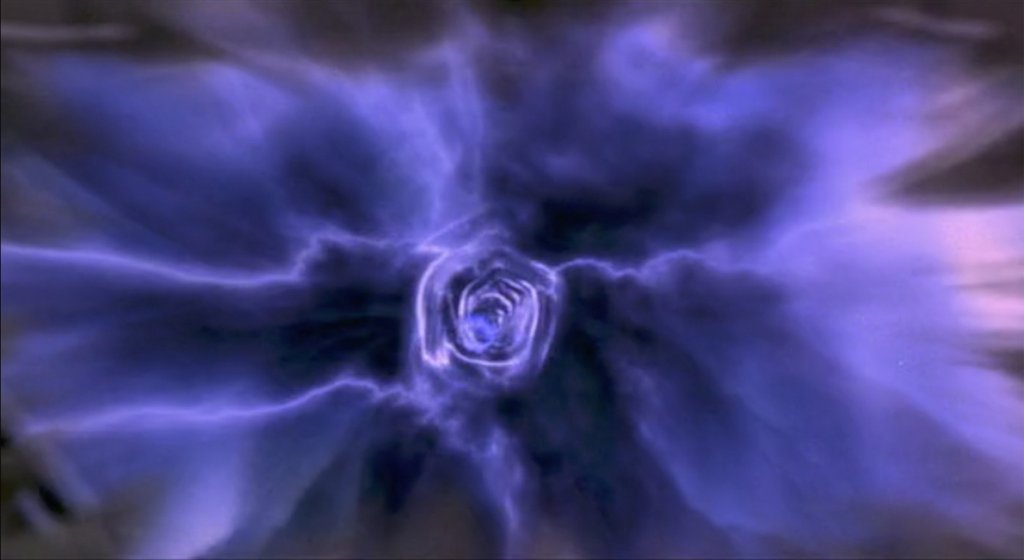

“Using appropriated footage from popular film and television, The Three Freedoms constructs a film of constant movement. Graphic and abstract depictions of faster than light travel, time travel, and interdimensional travel flow endlessly into one another. This winding, spinning journey inward echoes the “Phantom Rides” of early film history while imagining an improbable future.”

soon our bodies will be buildings

Tessa Bolsover

February 25, 2017

Viewable from outside 1605 E. Madison Street

Look South

In times of grief I turn to the idea of the body as a collection of materials. Our bodies exist for only a brief moment: a coincidence of molecules, soon to disseminate into countless other forms.

(I dropped a stone into a lake and for a moment, where the two surfaces met, a sound existed—)

Composed of found footage, text, and personal videos, soon our bodies will be other buildings is a meditation on the transient nature of matter and the constant cycles of molecular and contextual re-formation.

Drawing from the musical technique of phasing — similar to choral rounds — two video sequences loop at different tempos, so that the relationship between frames are realigned with each repetition. Over time, the piece is split open and reconfigured so that we can see it in its various possible forms.

Image Info: soon our bodies will be other buildings (found footage still), video, 2017

www.tessabolsover.com

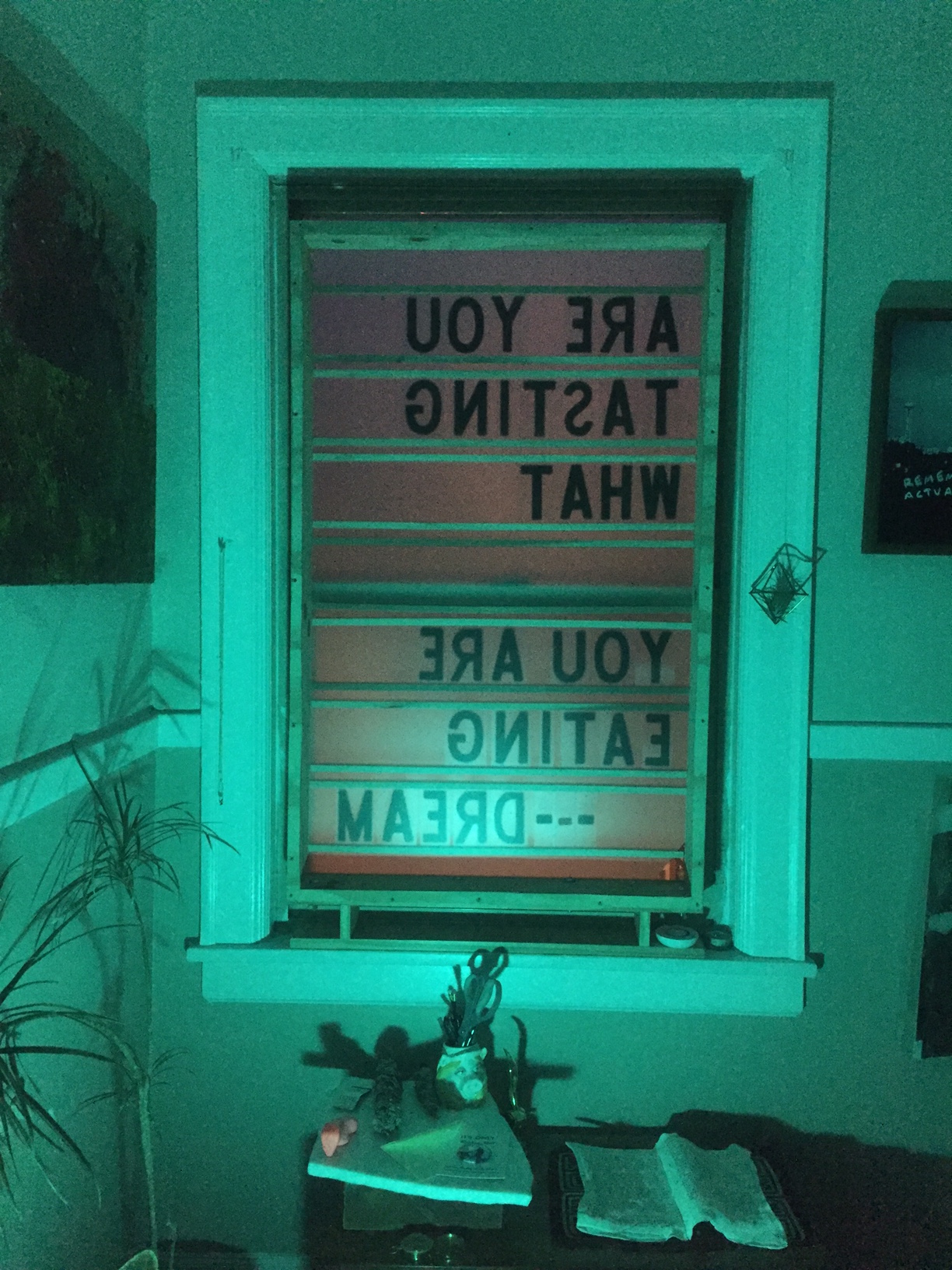

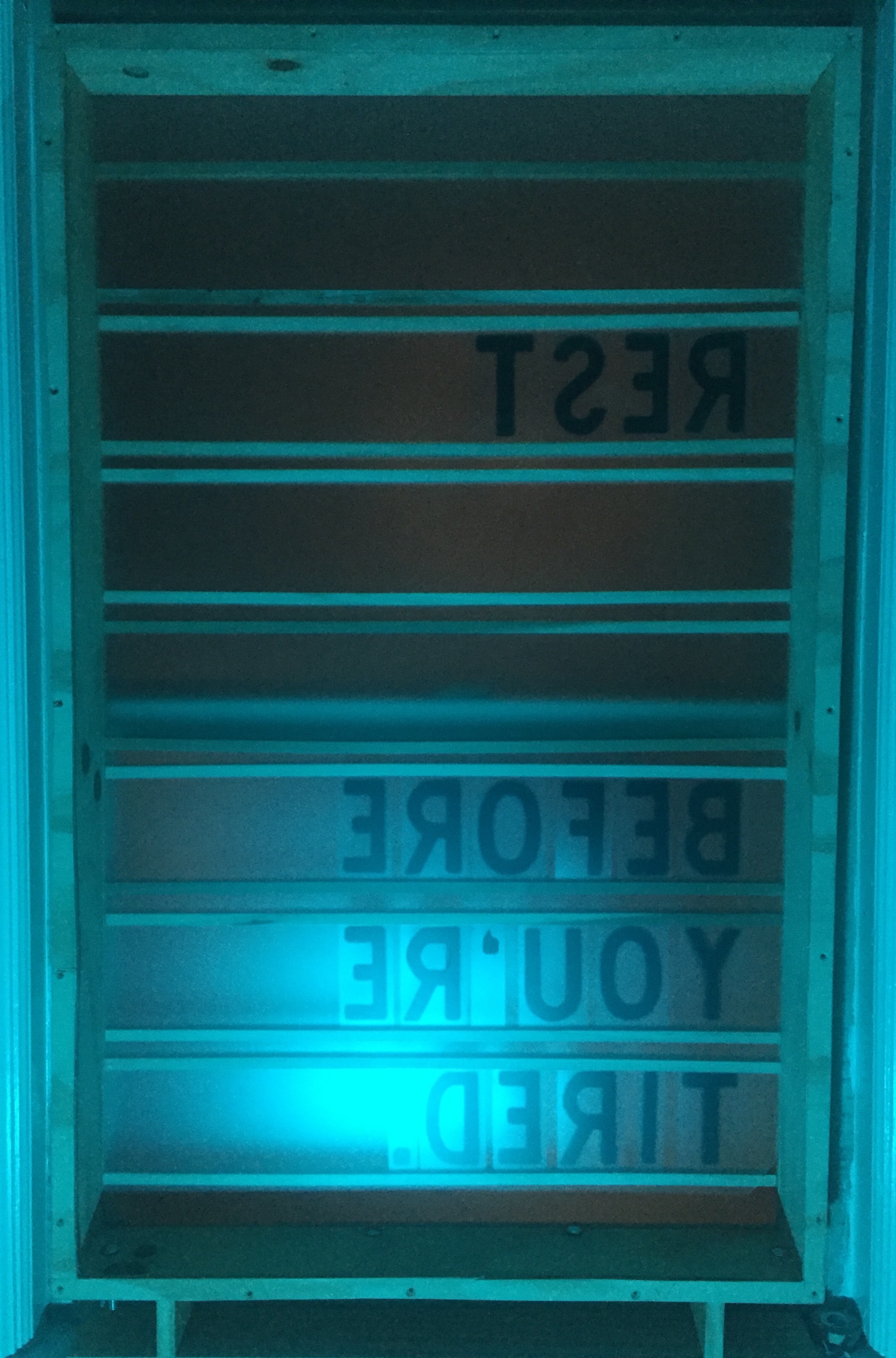

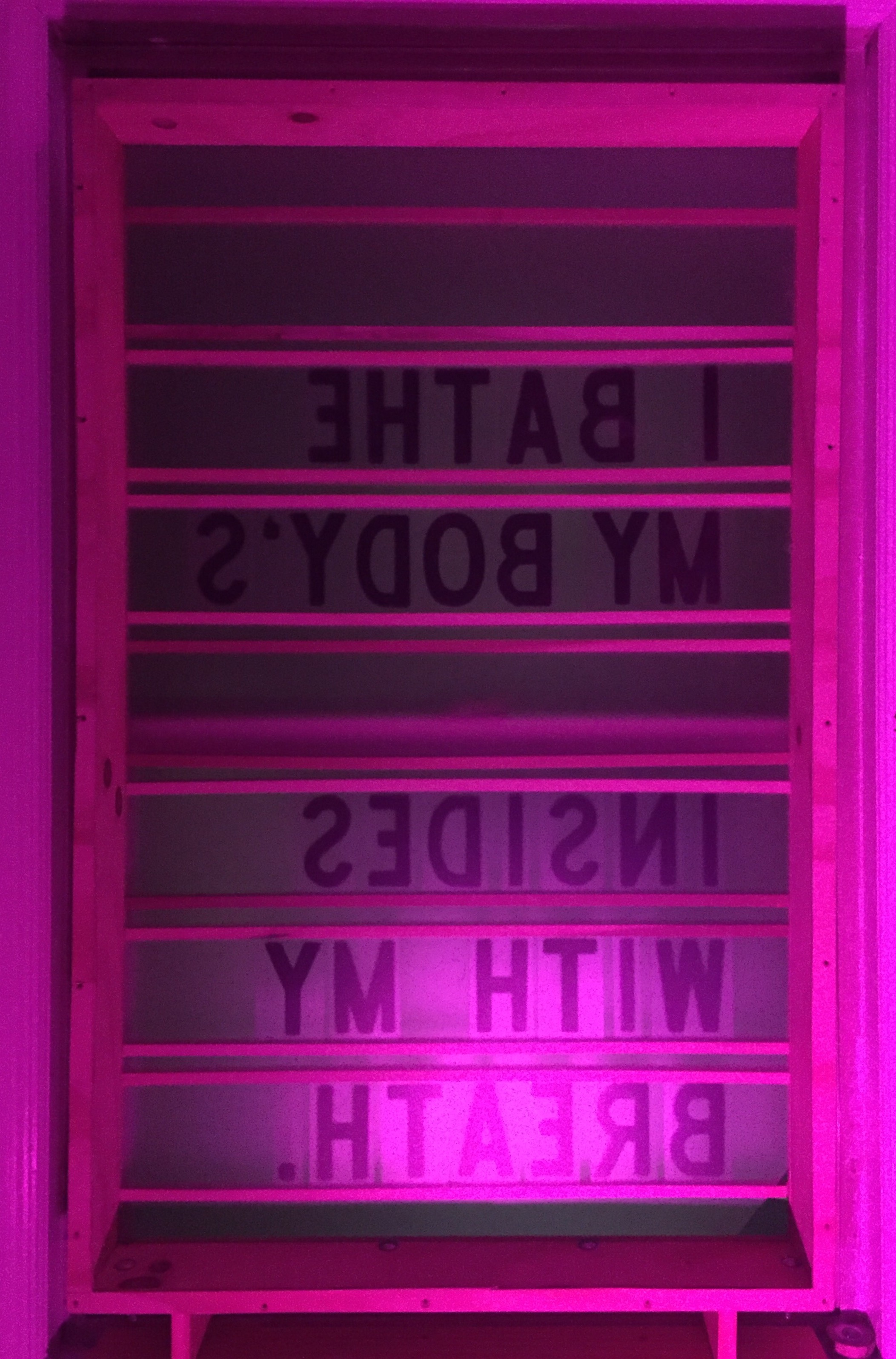

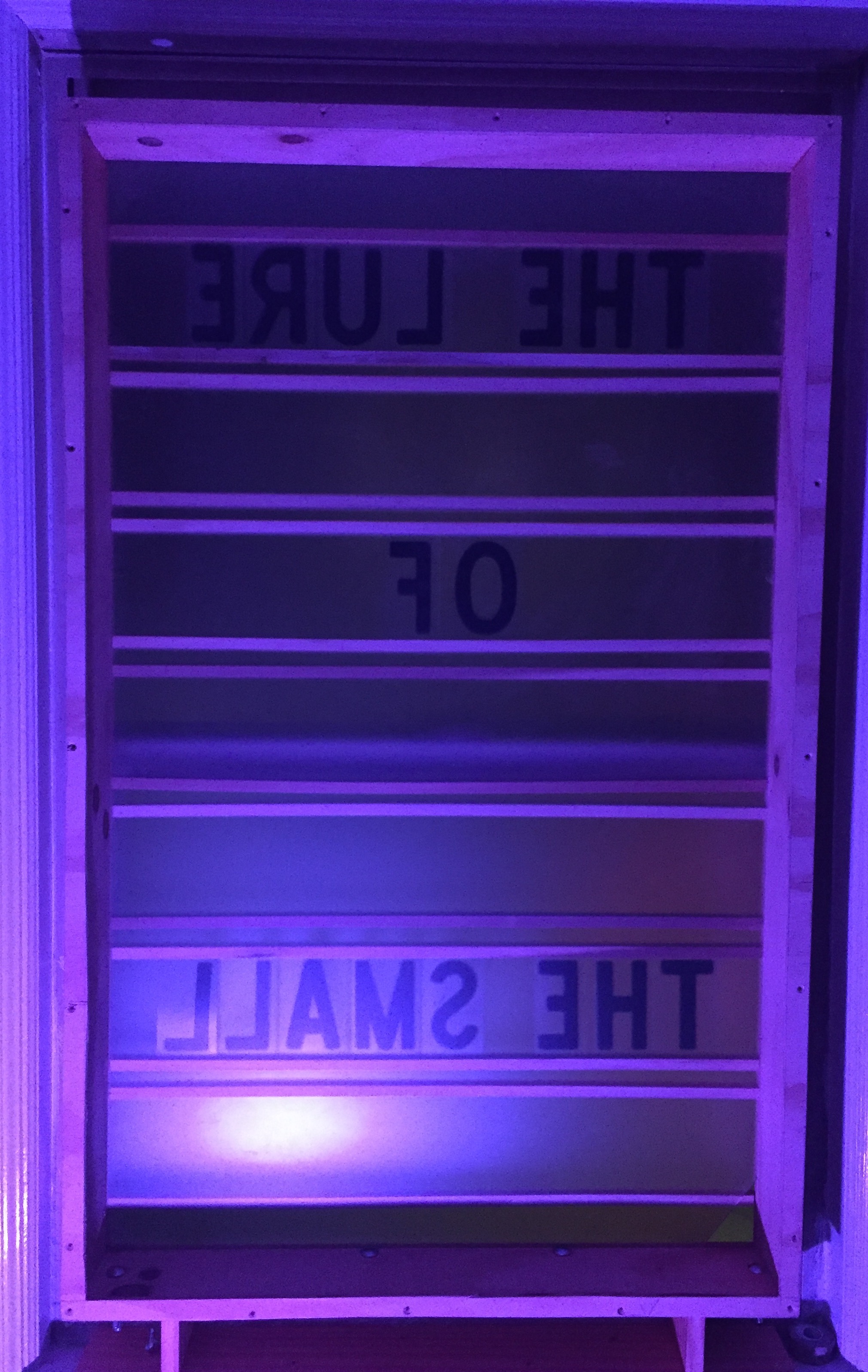

Illuminated Manuscripts

Kat Humphrey

Sunday–Thursday

February 19–23, 2017

sunset–sunrise

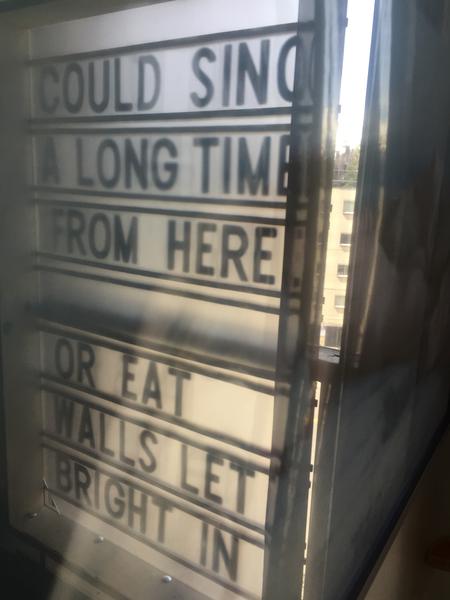

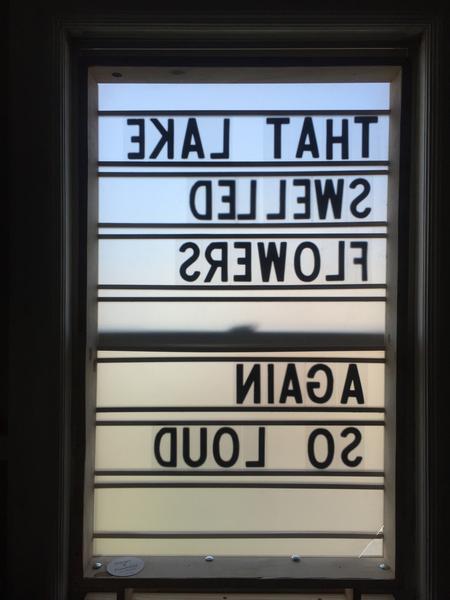

Each night for five nights, new text viewable in a window

“It’s common advice for writers to write what they want to read. These texts are offerings of words from dream, thought, and conversation that I enjoy revisiting, and would appreciate coming upon illuminated in a night window.”—KH

Kat Humphrey has a history with signs, and with visual art and text. She studied American Sign Language for many years and worked as an art therapist at the New Mexico School for the Deaf Preschool. She participated as a writer in a collaborative show of women writers and visual artists—Voices and Visions—in two galleries in Santa Fe and Las Cruces, New Mexico. She had a four-month solo show of photographs of fading signs on brick buildings at the former American Advertising Museum in Portland, Oregon. She earned a Master of Art Education / Art Therapy degree from the University of New Mexico. She has exhibited text-based and non-text-based art, and her writing has appeared in publications including the Seattle Gay News, the Raven Chronicles, and the forthcoming anthology Poets Against Hate. She has taught creative writing (poetry and prose poetry) in Seattle through Writers in the Schools and the former program Powerful Writers, and as an intern in New Mexico at ArtStreet, a program of Albuquerque Health Care for the Homeless. She has curated art shows and a related short lecture series. Over the past year and a half, she has been performing personal stories through the monthly storytelling series Fresh Ground Stories.

More about traditional illuminated manuscripts here.

Sunday dusk–Monday dawn:

Monday dusk–Tuesday dawn:

Above text used with permission of a friend and her quoted father.

Tuesday dusk–Wednesday dawn:

Wednesday dusk–Thursday dawn:

Photographs above by Sierra Stinson

Thursday dusk–Friday dawn:

Photographs above by Robert Wade

The Usual Window

The Usual Window

7 Poems for 7 Days

January 1st – 7, 2017

Sunset to Sunrise

viewable from outside El Capitan Apartments

Positioned where Melrose and Yale avenue meet

look up and out east

The Usual Window not only refers to the return of Vignettes Marquee to its original location, but also a childhood bedroom window, where the voyeur next door was often to be found, peering.

Valuing privacy over being seen, I cultivated techniques to disappear my body and exist only in words.

Text is my avatar.

I place my alphabet self back in the window for the first 7 days of January, each day new text in the marquee and an edition of 10 letterpress printed poems of that day, which I will give away on my usual routes through the streets.

See you there.

Bonus Track ‘ DEFLOWER THE PATRIARCHY’

www.bremelopress.com

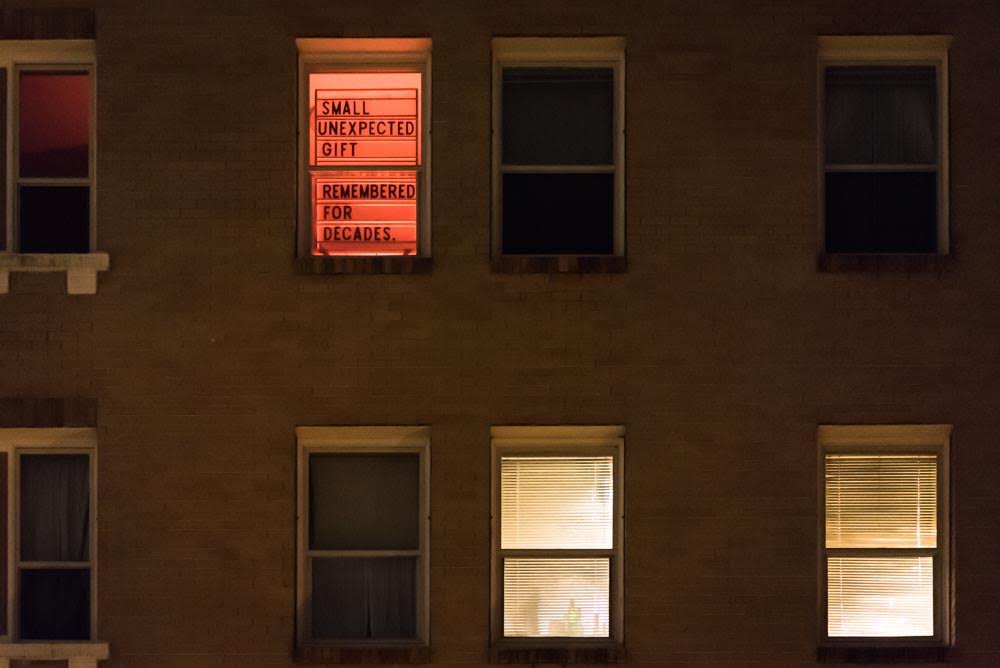

What Feels Most True: A Dream Hypnosis for Radical Awakeness

Laura Sullivan Cassidy

with found + collected family slides and digital images + audio

by Erin Sullivan

December 29, 2016

This exhibit is located outside on the corner of Bellevue and Pine Street on Capitol Hill. We will stand gazing into the windows of what once was the beautiful furniture store known as Area 51.

“When I was 10 a man calling himself a magician showed up in my hometown and took to the stage, pulling rabbits out of hats and “hypnotizing” citizens who then quacked like ducks and tasted vinegar when they were given plain water. Upon the backwards count of three, they remembered exactly none of it in accordance with his bellowed instructions.

From the 1800s to the ’80s, performative hypnosis was a mostly harmless hustle; in this current reality it’s a sort of assisted self-help. Just dial up a sleep induction on YouTube or download a podcast to stop smoking. Or drinking. Or eating. Or needing.

What Feels Most True is somewhere between performance and persuasion. Under a black no-moon sky, outside an urban ghost town at the dead-end of the year, images like strobe lights and words like wands are meant to rearrange natives, immigrants, and passersby alike. The quasi-narrative, two-channel, glass-enclosed slideshow will reimagine the villagers; remember them, forget them, and return them … back to where they were when they started so long ago: Pure and whole, tough and tender. Home. Alive.

And I’ll be there with them—making those return/transformations, too. Because I need to shift out of this bad dream just as we all do, and because like the magician and the hustler, there’s something I have to prove, not only to an audience but to myself.

All sickness is homesickness.

All hypnosis is self-hypnosis.”

—Laura Cassidy

Unfolding

Erin Elyse Burns

November 10, 2016

located outside on the north end of 1617 Yale Avenue

see you on the street

Rituals are sophisticated ancient intelligence about the body. Kneeling, folding hands in prayer, and breaking bread; liturgies of grieving, gathering, and celebration — such actions create visceral containers of time and posture. They are like physical corollaries to poetry — condensed, economical gestures that carry inordinate meaning and import. Rituals tether emotion in flesh and blood and bone and help release it. They embody memory in communal time. – Krista Tippett

when the caustic cools

Vignettes Marquee is pleased to present the solo work of Mel Carter

October 27, 2016

outside of 1617 Yale Avenue

see you on the street

what do you do in a place where everything rejects your touch?

let your guard down, go quiet / silence, don’t draw attention, try to listen anyway

she stands her ground, her quiet blooms saying “i need a little privacy”, and her defenders react the way they should when another unexpectedly breaches her privacy. you yelp and pull yourself away quickly, examining only your own injuries while simultaneously sucking your thumb (lmao a.k.a. lamenting my anguish online) and exclaiming “FUCK FUCK”. a brash kick directed at her trunk, you shuffle away uncaring and pissed with a “why do these things always happen to me/woe is me/this place is stupid” mentality.

No one will miss you here.

She blatantly warned you, how could you not see i do not know —

she exists solely for herself and tries to hold enough water to continue as always, with a little extra for friends/passersby (what’s the difference when you’re both going through the same thing). she provides for others, a selfless act in a place where she is her only defense.

Why was your immediate response anger to another who overtly advised caution? when she has been conditioned for these harsh environments why would it be her fault to exist just as she was created, because another was being thoughtless? Tell me how it’s different from your broken skin. why solidify that anger by adding insult to injury, memories swelling like skin around your actions; her only defense as she grows towards the sun is further preparations for future hurt. it’s these small things that seem to affect me more and more these days; if you’re doing this to something you seemingly don’t care about, what will you do when something really angers you? similarly to you (maybe, but your lack of sensitivity makes me doubt this) and your injuries, why would i not prepare myself for your own negative potential?

how can we care for, how can we caress and support these solitary beings, unused to touch or affection. how can we be tender — there are many things words cannot do. the language of careful touch, our first introduction and most primal language, feels so natural to me. it’s not just about lovers or specific partnerships, more of a how to provide genuine affection and non-verbal support in everyday context, so it doesn’t feel so foreign when it’s given sincerely. pulling away, is it me or is it the standardized lack of nurture here? leaving the sun and returning to cold, how do you find that tenderness and care you require? maybe others don’t crave that which you do, but wouldn’t it be nice to try a little tenderness?

IMAGE: when the caustic cools, (Still) Single Channel Video, 2016

www.cartermel.com

Tragedy Fragments

By CL Young

Wednesday April 13 – Sunday April 17

Sunset (7:54PM) To Sunrise (6:25AM)

This Wednesday through Sunday a new poem written by CL Young will be viewable every evening when standing on Melrose Avenue across from 1617 Yale Avenue

Look up west.

“THIS SERIES OF POEMS IS LOOSELY TIED TO A LARGER PROJECT THAT INVOLVES BEING HALF-ASLEEP.” – CL YOUNG

CL YOUNG WAS BORN AND LIVES CURRENTLY IN COLORADO. HER POEMS CAN BE FOUND IN GLITTERMOB, PEN POETRY SERIES, POOR CLAUDIA, POWDER KEG MAGAZINE, AND ELSEWHERE. SHE IS FROM BOISE, IDAHO.

#MARQUEESEA

Special thanks to Estee Clifford for constructing the Marquee

Image: Photograph by Sierra Stinson of reflection from Photograph by Doug Newman