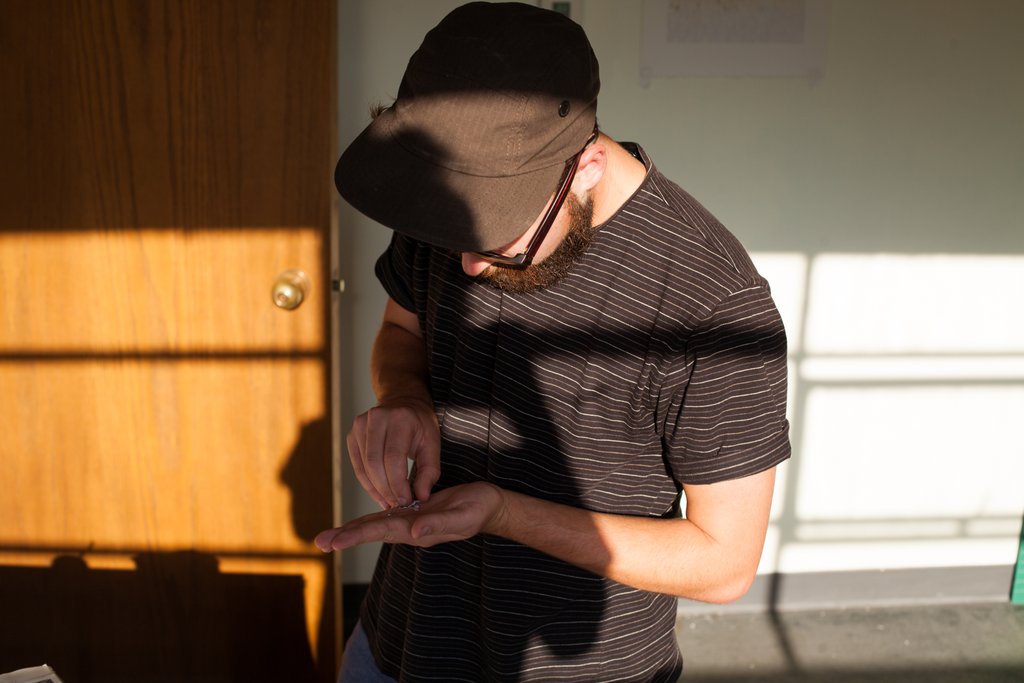

Interview by Adam Boehmer | Photographs by Andrew Waits

We are unsure why the sun is out in late Seattle winter, pouring through Rafael’s kitchen window and onto the photo strips hanging on his refrigerator. Small moments, sequential, black and white; time spent in Capitol Hill bars with friends and lovers. The panes of his vintage windows frame everything in the room similarly in the bright light of late afternoon.

I first met the Seattle-based photographer and artist Rafael Soldi 4 years ago, soon after his rather tumultuous move from New York City. His lover had literally disappeared, walked-out on the relationship, lighting a match and watching everything burn.

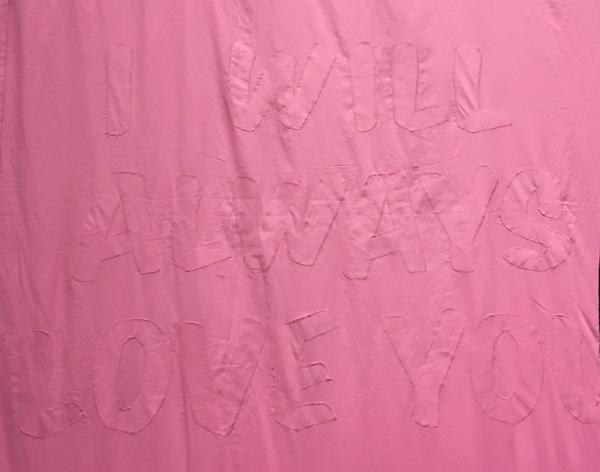

The full emotional upheaval of this has been encapsulated in his celebrated series “Sentiment”, which showed in its entirety for the first time in Seattle at Greg Kucera gallery as part of the exhibit “In the absence of,” following a solo exhibition at the Griffin Museum of Photography in Boston. In the series, moments out of sequence: Rafael and his lover posing in shadow and light, yellow flowers shrouded in heavy lace curtains, the bravery of a self portrait in this emotional aftermath, a mass of black balloons left as a gift in a sterile apartment hallway. All of it exists as a chosen documentation of intense loss and release.

BOEHMER: How does it feel to finally have Sentiment exhibited fully?

SOLDI: This work was made a long time ago and though I’ve shown parts of it numerous times over the last five years, seeing it all together on the wall for the first time is really exciting and cathartic. It’s been such a long time since the actual events that prompted this work that I have so much perspective and I experience these images on a very different dimension than before. The installation at Greg Kucera Gallery was very satisfying because the size of the room really allowed viewers to step back and see the whole thing, and the work by fellow artists curated around it also informed the piece nicely.

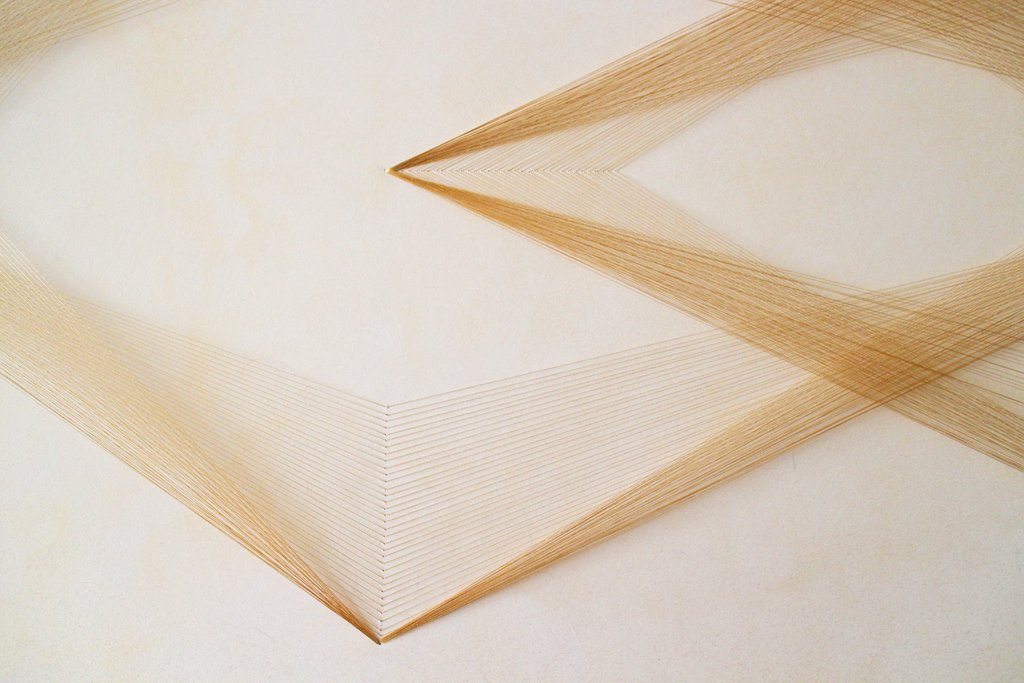

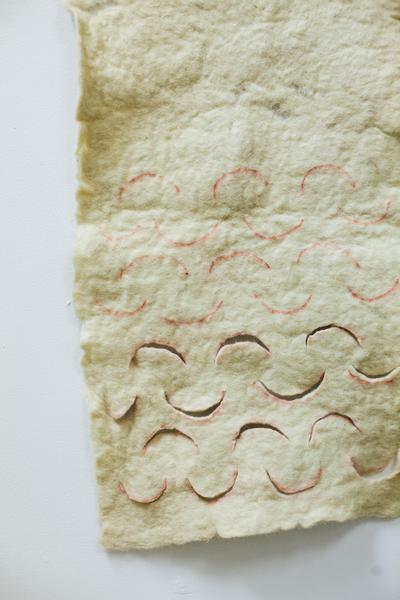

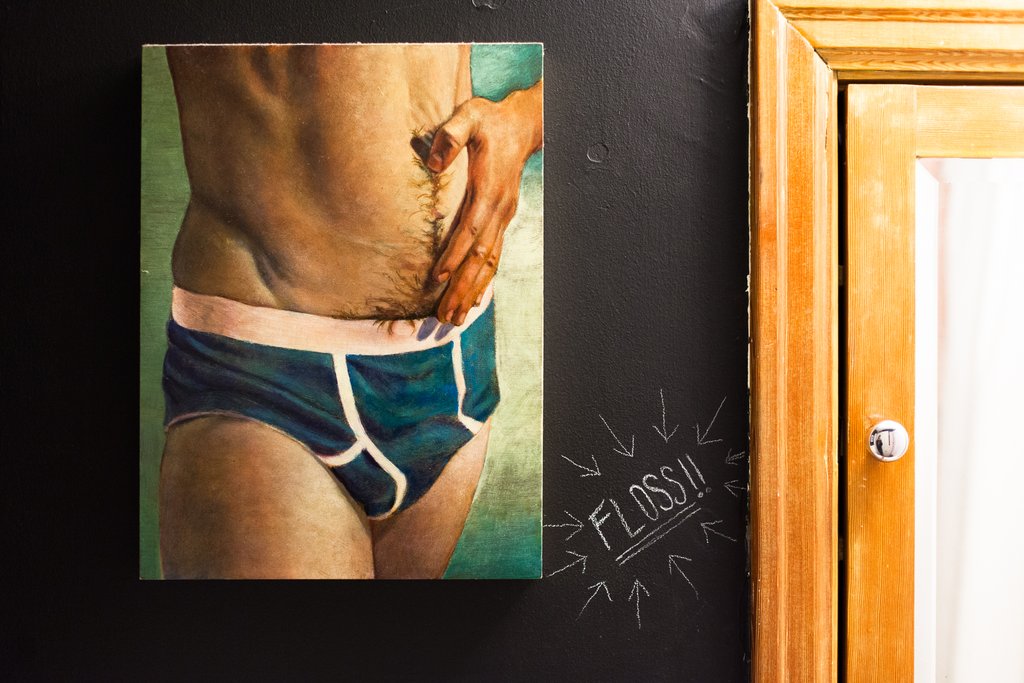

We drink tea and move around his home, which currently doubles as his studio. I watch Rafael shift from gracious host to careful vessel of thought each time I inquire about his process or new work. “For the first time, I couldn’t make pictures of the things I was trying to say,” Rafael tells me, as he explains his interest in removing himself from the narrative and diving into his subconscious for symbolic clues of what to create. The diptych “All Day I Hear The Noise Of Waters” is devoid of any of the color or light or narrative of “Sentiment”. It is a pair of dark and closely-cropped photographs of water that look as though they could have been chiseled out of onyx. The sculptural ripples carry a new energy toward some unseen shore.

BOEHMER: This work stems from the events that spurred the creation of “Sentiment”, yet the finished work is entirely different. Talk with me about your conceptual shift.

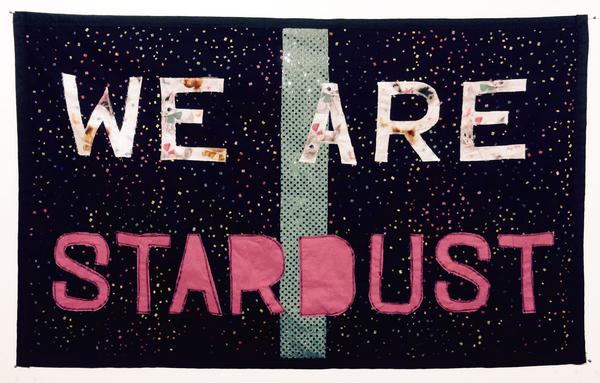

SOLDI: That breakup was a life-changing moment for me, beyond heartbreak. It introduced me to adult human emotions like fear, anguish, guilt, panic, and regret. In the years that followed I began to notice an inner selfhood that I couldn’t define. Each of us has a certain resolute innerness, an abstract self that we don’t share with others because we cannot even define it. So while my earlier work was a direct narrative representation of what I was feeling right there and then, this new work is an abstract reflection on the consequences of those events. It investigates the private spaces within me that I shield not from others’ eyes, but from my own. These new works explore my growing awareness of my spiritual subconscious and my fears. For the first time I am taking a conceptual approach, rather than a narrative or representational one.

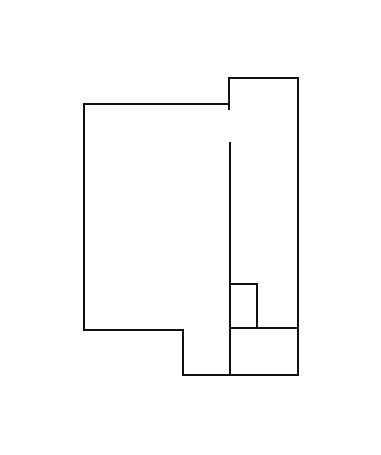

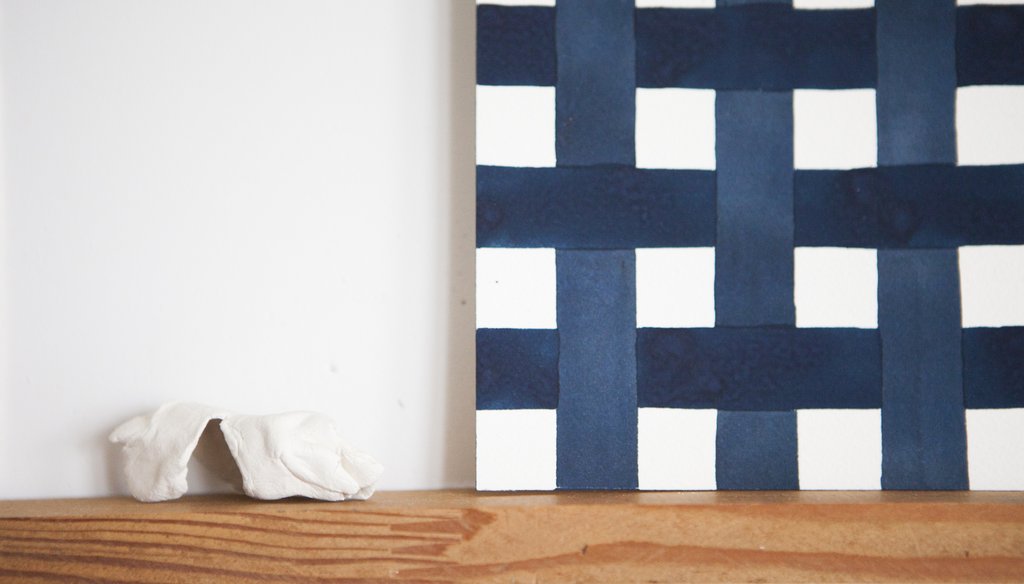

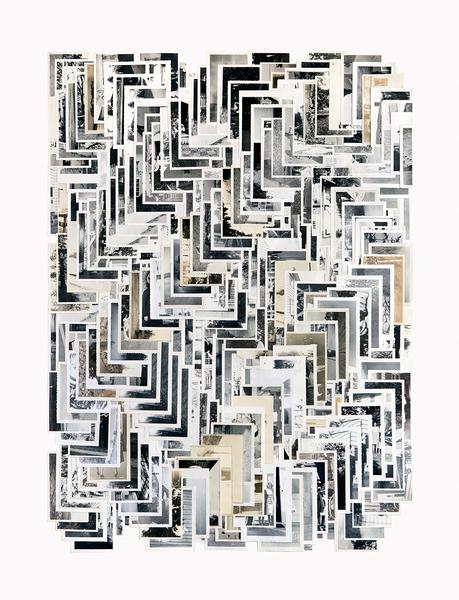

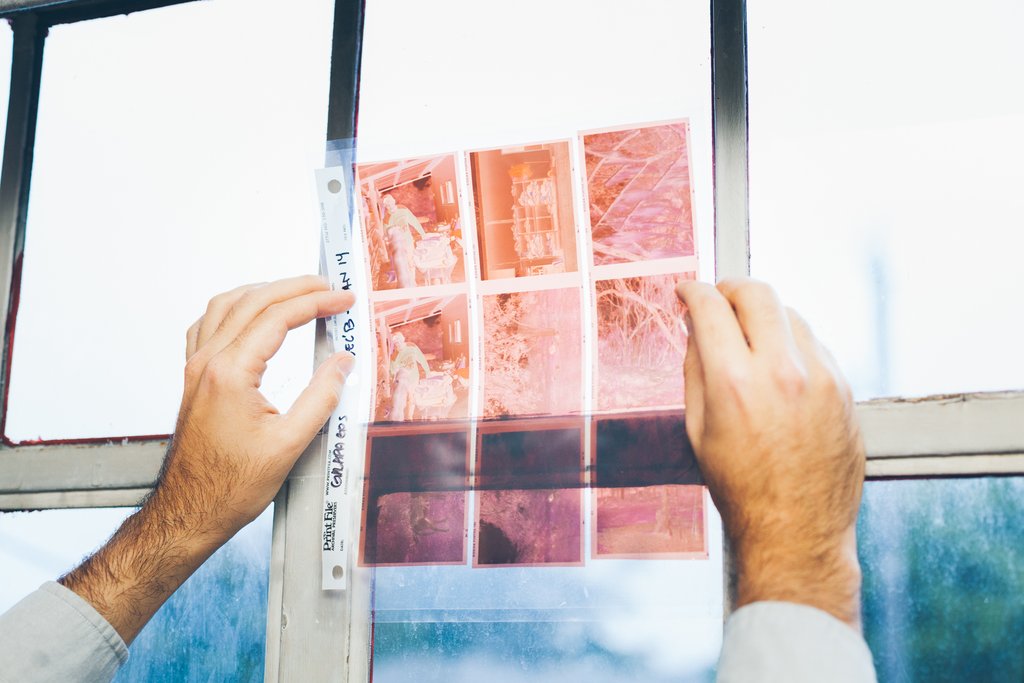

Rafael spreads some newer work out in his studio for us to peruse, specifically a series called “I Choose to Remember/Forget”. What appears to be a grid of white rectangles lifted just slightly from their backing turns out to be photographs of him and a past lover mounted backwards. They were sent to him in a box from his family, who had been holding onto some of his personal effects while he moved to Seattle. A box of memories he didn’t want to keep, but couldn’t get rid of.

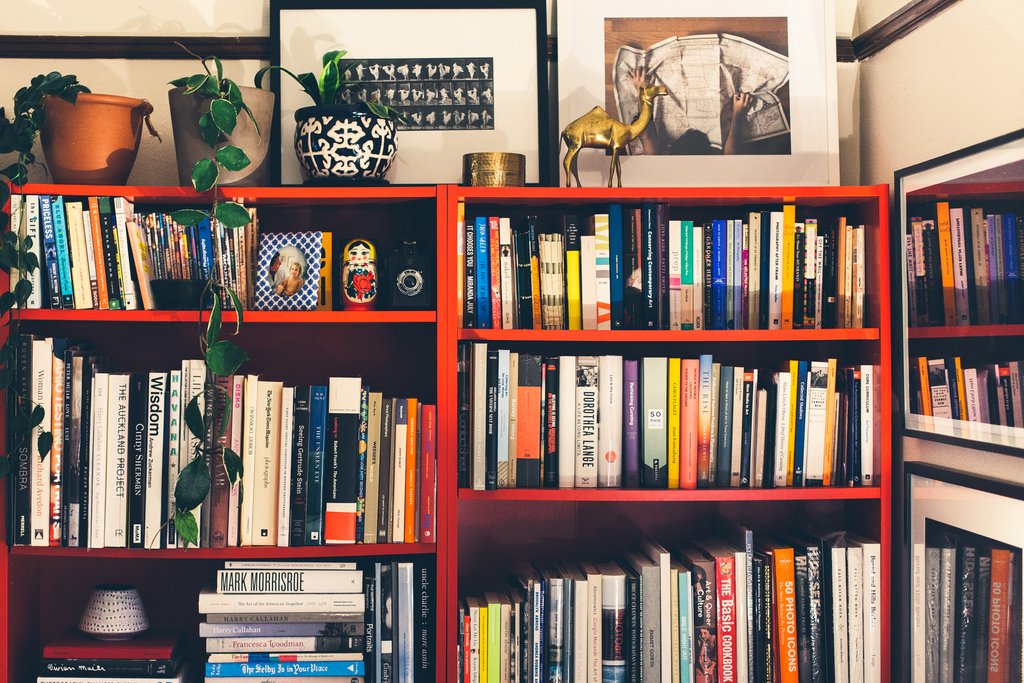

“I like these because they’re orderly, beautiful, sensible…” he says. His apartment reflects this: every object, book and piece of furniture meticulously placed and ordered. The photos indeed look intentional, but also quiet. Their immediate language is limited to the slight shifts in light, texture, and color. Knowing that on the other side of each object is an image, a memory that might not ever be seen again is jarring. “Do you remember which photograph is which?” I ask. “No,” he says. “Not anymore.”

BOEHMER: Memory is such a huge part of your past work, and now you’ve added this new futurity into the mix. How do you feel time is represented in your current work?

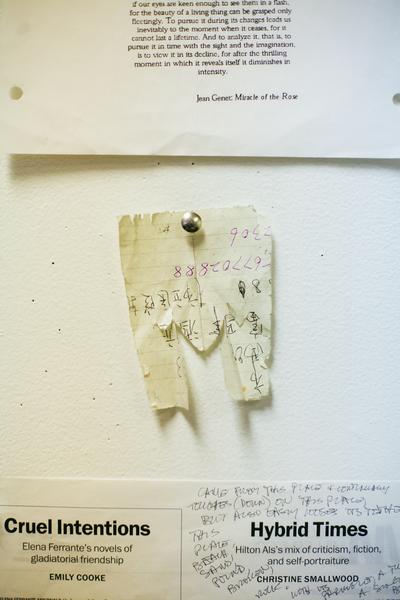

SOLDI: I’ve spent a great deal of time thinking about memory and the way we process our past, and how we deal with it on a daily basis. Concepts of time, in a variety of ways, show up quite a bit in my new work but usually in a somewhat abstracted way. The new works are meant to be read in more than one way, they are based on my own experiences but they are not explicit, I want viewers to get a sense or a feeling of what they are looking at but fill in the blanks with their own experiences—they are essentially screens. “I Choose To Remember/Forget” definitely deals with memory which is inherently linked to time. Another piece titled “And All of a Sudden You Were Gone” is a grid of photographs that loosely resembles the physical depiction of a timeline. Untitled (XIV) depicts the back of a man’s head looking into a black expanse, which I interpret as looking into the past.

We end our studio visit with a viewing of a concept for a new piece that is a complete departure from photography: a pair of full-scale black facsimiles of Michelangelo’s “David”. They appear to stare into each other’s eyes. Their presence is intense, and I imagine these two dark lovers or twins or brothers caught observing each other’s frozen beauty for eternity. Or maybe their gazes just miss, their only view of each other off-center, forever stuck in each other’s dark periphery.

“I see my work as this long thread that is catching all these experiences”, Rafael tells me. “There’s a soul, a privacy, and an innerness.”

It has grown darker in the apartment and we both take notice. I gather my things and we exchange farewells and part ways. Walking into the early evening, I catch the dark windows of different apartments and houses brighten with lamplight. We are all getting ready for the night.