An essay and conversation between Gretchen Frances Bennett and Laura Sullivan Cassidy

Pure and whole, tough and tender. Home. Alive.

I first met Laura Sullivan Cassidy on a rainy night, sheltering in the doorway of the El Capitan building, home to the Seattle art venue, Vignettes. Our conversation, I believe, started with the weather. We were there to see Mel Carter’s “When the Caustic Cools,” projected on a building across the street, and we talked about the rain letting up.

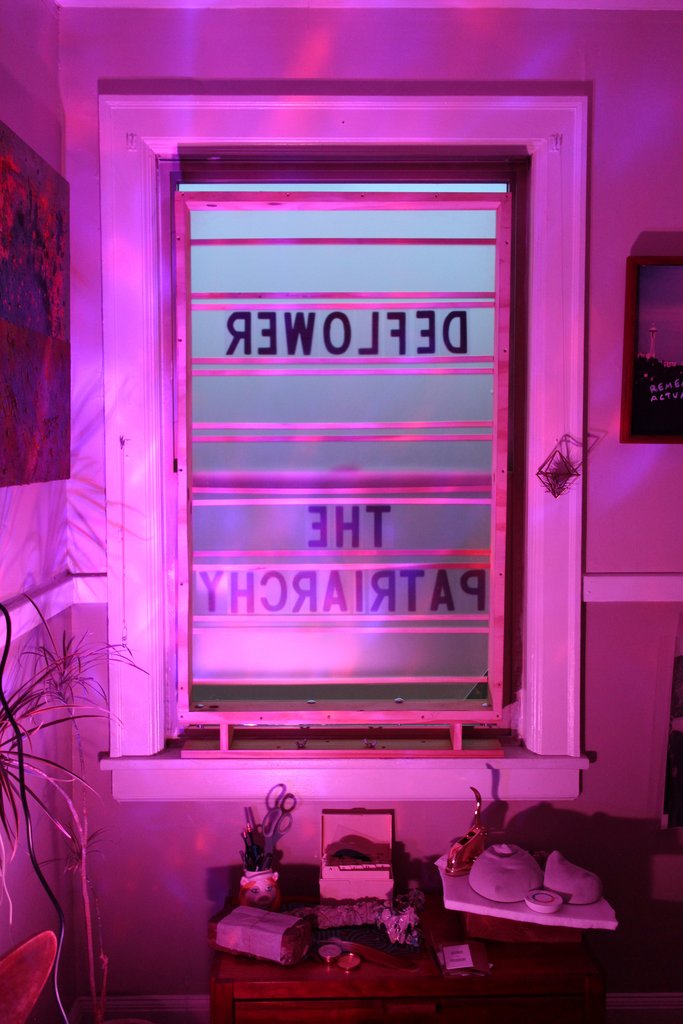

We met next on another wet night, when Vignettes Marquee presented Laura’s work, “What Feels Most True: A Dream Hypnosis for Radical Awakeness,” a two-channel projection of “found and collected family slides and digital images,” accompanied by a dreamy abstract audio track by Laura’s husband, Erin Sullivan. For this one–night–only presentation in a storefront in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood, images cycled in slide show cadence, sometimes superimposed with san-serif text: “Three / Two / One / Before you can begin you must open your eyes / See the tattooed tear drops / See the watcher watching / See the knower not knowing a thing / Now, with your left hand, smooth the wrinkle that will not iron out / And with your right hand: feel / Can you feel warmth in what you’ve forgotten? / Can you feel pretty when you fall? / Then, say that we will find a way to reach each other / Say that you did not dream of airplanes falling from the sky last night / Say that you have not been having that dream for as long as you can remember / Say that you know nothing / Say that you have nothing / Say that you want to give it all away / Because what could feel more real? / What could be more true? / All sickness is homesickness / All hypnosis is self-hypnosis.”

Laura describes this work as being “somewhere between performance and persuasion… images like strobe lights and words like wands are meant to rearrange natives, immigrants, and passersby alike. The quasi-narrative, two-channel, glass-enclosed slideshow will reimagine the villagers; remember them, forget them, and return them…back to where they were when they started so long ago: Pure and whole, tough and tender. Home. Alive.” A promotional image for “What Feels Most True” is titled simply “Found Family Image, Kodachrome Slide.” This image, depicting kids floating on deep blue water under a slightly less deep blue sky, is both strange and known, like most photographs in this work. We see weedy gravel in front of white industrial garage doors, a hand feeding a bird, sea life, twin moveable jet bridges leading to no airplanes, side by side statues with caution tape necklaces, all brined souvenirs of absent animals, plants, dirt, watery nights, and stars.

We met next at her house, and talked about being ourselves, being tied to the weather, how we weren’t sleeping, and about our fathers, both scientists who passed away and left us image collections. We ate kale and listened to Henry Flint’s Raga Electric on vinyl. Later, Laura sent phone photos of her father, Paul M. Cassidy’s dive journals, pulling out phrases, like “Nothing really unusual,” and “Much too turbid.” “There were specific crabs my dad was studying in the Philippines. He told me he found a species no one knew about, he tacked the name ‘Paul’son’ there on the end, you can see it on the cover (of a dive journal)”. “I’ve understood much more about my need to notate and document, since going through his things. What a diarist!”

As I get to know her, I take any occasion to talk with Laura Sullivan Cassidy: in person, in weather, by text, or, in this case, by email.

Gretchen Bennett: I saw an electric window sign in the International District, signaling both open and closed, when unlit. I thought of it, with your work. Do you look at the family slides as both open and closed spaces, and do they provide clues to your past and to your father; and, something that stops and can’t fully show itself?

Laura Sullivan Cassidy: Absolutely. I probably wouldn’t have used those words—open and closed—but they’re perfect.

After my dad retired he took ownership of all the family photos and slides, and scanned them in. He gave us all copies, and I’ve always loved family photos so I’ve always had them at the ready and I’ve periodically gone down rabbit holes with them, but I really and truly binged on them after he passed away. When I go into the folders now (he separated them via era: ’60s, ’80s, etc.), it’s as if the lights are on and the door is open but no one’s home. I can get in and look around, but there’s really no one who can answer my questions or show me around.

So yes, open and closed.

GB: I have a collection of Kodachrome slides from my father. When I rediscovered them, I had less a memory of the imagery, and more a memory of him taking them. Are images from our lives something we want, but we may need to forget about for a while?

LSC: That feels right. I somehow want it to be more right with the old Kodachrome stuff, but it may be most true with our iPhones. Most of us do this capture, capture, capture thing, and I suspect we really don’t even know why we’re documenting the sunset shadows or the dinner party or the art show or the cat sleeping. It’s reflexive at this point, but it can prove useful, too. How often do we say, “Oh I forgot all about this picture!” when scrolling through our handheld archives? My mind tends to be really busy all the time and I’m always mentally juggling, so I am forever finding things I have forgotten about. Images, notebook pages, groceries even!

Maybe we don’t need a cure from/for them, but gaps, keeping us separate from them, are good? So, when we realize (again?) that they are, it’s like more life?

I feel myself trying to name what that pay-off is. Are they more like life, is that what the reward is? I think for me, because my memory is sort of foggy and spotty, the reward is the opportunity to piece it all back together. The opportunity to tell or retell a story.

Some images provoke a visceral response and you’re back in that moment instantly, but some are more slippery than that, and that’s okay with me. I kind of like not knowing. I kind of like the soft, vague tether—and I’m really grateful for that. My memory has been weird ever since this medical event I went through a few years ago, and I wouldn’t have predicted that I’d be okay with the fog, but I really am. Images do sometimes clear things up, but for every image that offers clarity, there’s another that is impossible to place, name, tag, number, or hold on to.

GB: “The quasi-narrative, two-channel, glass-enclosed slideshow will reimagine the villagers; remember them, forget them, and return them…back to where they were when they started so long ago.” It seems that they are returned to a new home each time, given the looping course of the images, I find that exciting. “And I’ll be there with them—making those return/transformations, too.”

Isn’t this a way of moving forward, saying both hello and good-bye, letting go pieces at a time, as if through “strobe lights?” Not to forget, exactly, but to remember, like talking and listening at the same time, so that every moment is a living moment, and this living is not separate from the imagery, but on it, like dust and fingerprints.

LSC: Absolutely, the goal really was to create a bit of a mind-scramble. I truly meant it as a hypnosis or a meditation; a way to wipe the screen and get rid of some negativity and replace it with some wonderment and remembrances and curiosity.

GB: Are these found photographs also remembering and forgetting in front of us?

LSC: I seem to want to hang on to them as not quite fiction and not quite non-fiction, so I suppose they are remembering and misremembering.

It’s like how we all have different memories of any one event, right? Especially because film (as opposed to digital) forces and allows us to capture and retain a lot of imperfect, in-between moments, I feel like what the old pictures do is lob little moments at us and those moments aren’t true or untrue. They aren’t giving us back that day in 1979 and they aren’t taking it away. Like an argument in the matriarch’s living room about which uncle owned the white Pontiac station wagon, they are saying, “Hey look, the past isn’t something you can hold on to.”

And I guess I want that to also be a reminder that you can’t hold on to the present or the future either. None of this is completely knowable. Not all of this is nameable. Ten people in any given room, on any given street corner, see ten different things. Is it weird that I find that comforting?

GB: Not weird, at all. I see your work as elemental — the everyday we all know. But I also think the work is biased towards your particular sensibilities. Not only with “What Feels Most True,” but I’m thinking now of a line from Mountain Lakes, from your recent book Backyard Birds Barking at Planes: “Never has our greed been so pure and so right. Never has it been so difficult to leave a place, never has it felt this cruel.” When I read this, I can see the lake the whole time. Everyone can easily reference their own version of a lake, and its transformative qualities.

From The Phone Call, also from Backyard Birds, is the limpid sentence, “Before all of this and any of you.” Here, I see a part of a life lived, a pause, and more life will be lived, in some sequence, like a slideshow.

LSC: I love that my stories can feel like a slideshow, and yes, what moves me the most are the incidental days when being human is kind of frozen in ice for minutes at a time, and then—poof—it thaws again.

I think where I have found my own place in writing, both fiction writing and in journalism, is in those particulars. I do take in a great deal. Retaining it? Depends whether I write it down or not. But I take in a great deal. I see a lot of what’s happening in shadowy corners and I hear things in pauses and stops and starts. I am not saying that those things are absolute truths, but what I pick up often really resonates. I have experience and confidence enough to admit that. I notice things, and I’m proud of that. And grateful for it.

GB: “What Feels Most True” seems to be as engaged with literature and performance, as it is with art. Do you relate to your work as a visual artist, more, or as a writer, and does this matter, for the work?

LSC: I have always identified very, very strongly and clearly as a writer but for the past ten years or so I’ve been very driven to do anything other than hand you a page of words and ask you to read it. While I’m certainly very interested in publishing, I’m equally interested in finding new and different ways to tell you a story.

In many ways, my roots are in music, so I have this weird and persistent metaphor about putting out a record or setting up a show at a club. I want to be able to do the equivalent of that within the literary realm. I think once I came to really good terms with the fact that my short stories are indeed really quite short, and that my fiction is more kinda-true than not-true, I felt even more motivated to do, well, to do weird stuff with my work. To do ‘other’ stuff with it.

I do a lot of visual stuff too, though. It’s true. I also really like collaborating with visual artists. I like illustrating my stories and I’m not sure I’ve ever put any of them out in the world without some kind of visual accompaniment.

GB: For me, “What Feels Most True” relates to Jonas Mekas’ documentary film As I was Moving Ahead, Occasionally I saw Brief Glimpses of Beauty, and how he compiled his home movies into a film, in the order the rolls came off the shelf, saying, “I have never been able, really, to figure out where my life begins, and where it ends.” Is this how you work?

LSC: Actually, I think I’m a writer because I’m trying to understand life. I don’t think it’s definitively possible, but I want to try. I want to put some of it down in a certain way that feels true enough. Like, I can accept this rendering of what happened, or what could have happened. Or what happened through this one particular lens. I am highly, highly motivated to understand things, but in a perhaps confusing way, I don’t have a death-grip on that understanding. It just feels good for a little while to feel like I have some resonating ideas about why and how.

But like all art and literature, once I pass the thing to you, you get to decide how you understand it. It’s a cool contrast with my life as a journalist. In that role, I want you to know for sure what I’m trying to tell you. But when I’m writing freely from the world around me, separate from work, I want to just decode this little thing I saw or felt or heard or did, and then I want you to hold on to it for a little while and decode it too. It’s a telephone game.

GB: Because you are not always the person who took the photographs, is meaning up for grabs; do you become free to assign meaning, based on what you know of the photographer, who is, in many cases, your father?

LSC: As far as I know, my dad took all the vintage images. There were some current/contemporary digital images in there as well, and those came what was dumped into laptop folders from a couple of digital cameras that Erin and I have shared over the years.

But in terms of the old images, the meaning is so up for grabs. Again, it’s a telephone game. That image of people riding flour sacks down the wavy yellow slide, god, I really have no idea. I think it’s out by the ocean somewhere. Like, we probably rode go carts immediately before or after.

What did my dad think he was remembering with that shutter button? I have no idea. Maybe he took the picture out of obligation or as a distraction; maybe he was thinking about work or his sore back or what he didn’t get to do as a poor Irish catholic kid in Tacoma.

But when I take that photo and layer some ideas on it, and give it to you, that one moment in my dad’s life is alive again. Ideally at least, it’s reactivated and it can do new and different things with whatever you layer onto it.

I wanted to take some of those old moments, and some less old moments, and put them back into the world—together with the reminder that we can trust ourselves and we can love ourselves and we can be ourselves. We HAVE to trust and love and be ourselves—mostly because if we don’t, it’s impossible to trust and love and be with others. It’s like that thing in planes: put your own oxygen mask on first, then help those around you.

I need to get my oxygen mask on right now, and my way of getting that flow going again is to remember who I am and what I am came here to do.

Laura screened Agnes Varda’s documentary film, “The Gleaners and I” in in her home, as a good-bye event for Vignettes founder, Sierra Stinson, moving to New York. In a “much too turbid” state of sleeplessness, I couldn’t attend, but I’ve seen this film multiple times. It follows gleaners, as they forage for food, and it points to itself, a film of images gathered and compiled by a woman, like “What Feels Most True.” An online essay on “Gleaners” by Homay King states that digital media disembodies and frees the referent from its frame, while “Gleaners” rematerializes the digital, by hooking it back into time and passing seasons. “Now, with your left hand, smooth the wrinkle that will not iron out / And with your right hand: feel.” Varda pauses to film one aging hand with the other.

Lifeforms of “What Feels Most True” are freed from their frames, and it is these depicted forms—a crab pincher, a woman—not their square matrices, that route themselves through our consciousness. At the end of “Gleaners,” Varda visits The Museum of Villefranche, and the painting that may have inspired her film. Edmond Hédouin’s “Gleaners Fleeing the Storm” is brought outside into bad weather. “To see them in broad daylight with stormy gusts lashing the canvas was true delight.” Her focus isn’t on the painting itself, but on the women running home with their wheat. And the wind kicks up.

Coincidence of Molecules

A conversation between Tessa Bolsover and Erin Elyse Burns

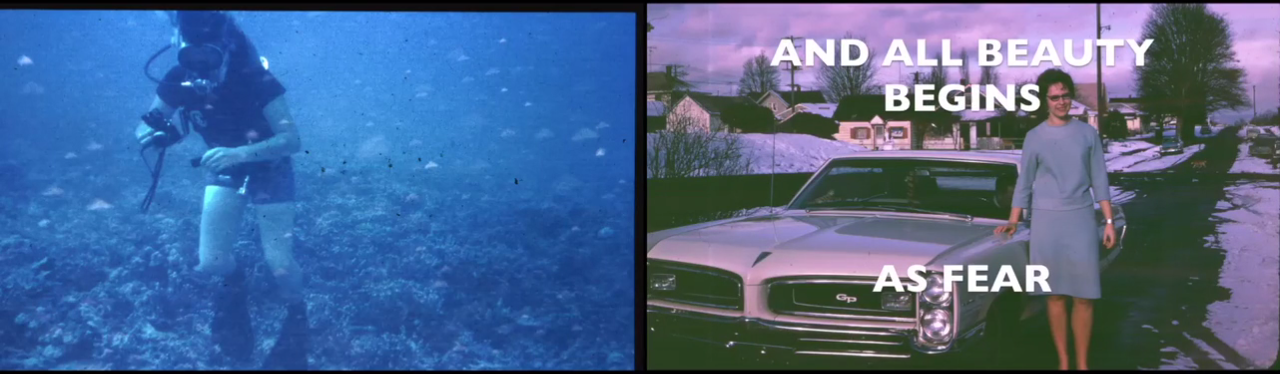

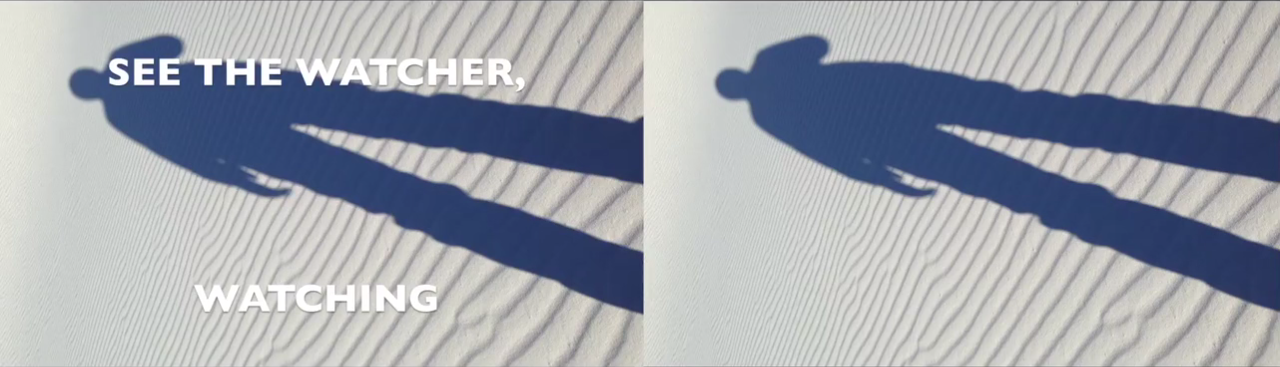

It’s a brisk winter evening – startlingly cold for Seattle. On a sidewalk in Capitol Hill, a group of people is huddled in front of an apartment building. There’s a quiet shuffle punctuating the crowd’s tempo – bodies shifting weight from one foot to the next, gently trying to ward off the chill. Just overhead are two windows filled with a video diptych that has a pace not unlike our own. Continuously moving over time, changing from image to image, and punctuated with evocative, fragmentary poetry. Tessa Bolsover’s Soon our bodies will be other buildings, on display at Vignettes’ Marquee exhibition series, calls upon environmental, molecular processes that evolve subtly. I have just returned to the Northwest after an intense stint in Nevada, saying goodbye to my mother, and feeling fairly certain I will not see her again. Grief is heavy on my mind. In Tessa’s project statement, she writes “In times of grief I turn to the idea of the body as a collection of materials. Our bodies exist for only a brief moment: a coincidence of molecules, soon to disseminate into countless other forms.” As I watch the video cycle through its patterned phases, I am struck by its lack of emotivity. A stick dragged across the snow. Deep sea divers swimming gracefully. Abstract macro imagery that looks like ice and snow through a microscope, yet I can’t help but see a pattern of human ears. Cells filmed through a microscope. A shadow falls upon a tree in birch forest. The camera enjoys the act of looking — the imagery inhabits real time. Through the lens of a biological perspective, I view beautiful imagery with a cool, scientific tone. I leave the night wondering if this is particular to me, or if Tessa has chosen an objective position as a strategy for the content of the work.

Erin Elyse Burns: The languorous imagery in Soon our bodies will be other buildings creates a certain calm that strikes me as reserved, almost without attachment. Will you speak to the emotional tone of your piece? Am I off in reading it as perhaps implementing the objectivity of a scientist?

Tessa Bolsover: I find a deep calm in the acknowledgement of the body as an entity within a large network. For me, observing becomes a kind of ritual to reintegrate with the strange and beautiful system of molecules of which my body is a part. I don’t see it as detachment as much as an attempt to empathize with the objectivity of the world beyond my ego.

Recently I’ve been reading a lot about the idea of Decreation (as re-defined in Anne Carson’s book of the same title), which basically means stripping away the self in order to get closer to the unknown (i.e. god). Observing the transience of materials is a way of stepping away from my mind and into my body, so to speak.

EEB: What lead you to utilize a looping imagery structure similar to the technique of phasing, as established by minimalist composers like Terry Riley and Steve Reich? Do you have a musical background?

TB: While working on this project I found the video editing process similar to the process of composing music. The concept of phasing had been floating around in my head for weeks, so utilizing an interpretation of the technique in my video looping process seemed like a natural fit. One of the main themes I was working with is the idea that molecules are constantly re-forming in various combinations, meaning that on a large scale, each object or entity can be reduced to a fleeting encounter between molecules, each following its own trajectory. Traditionally in phase music, two musicians simultaneously perform the same score at slightly different tempos, so that over time the relationship between the two players is realigned repeatedly, swaying between unison, echoing, and doubling. I wanted to extend this metaphor into my work by looping the two videos side by side at slightly different tempos so that the relationship between the two screens would change with each loop. Images and text fall in and out of unison periodically, putting the same emphasis on both order and disorder.

EEB: You work primarily in still photography – what has exploring the medium of video been like for you?

TB: I’m pretty new to making videos — it definitely had its share of challenges and opened up new ways of experimenting within time-based parameters, something I don’t usually get to do directly through my still photography.

EEB: You use both found footage and imagery you’ve captured – how do you approach this collage-like structure?

TB: Collage definitely feels like the right word for it. The footage I captured was a collection of gestures exploring the temporary physicality of my body within various landscapes. The rest of the imagery I collected through public domain archives online. Most of the videos I pulled from included little or no information on what the images were and why they were made — I found the combination of these sourceless videos and my own recordings an interesting juxtaposition and a way to contextualize the issue of interiority vs. exteriority.

EEB: Will you speak to the poetry you’ve written for this work?

TB: Writing is a huge part of my practice, although it rarely makes its way into my visual work. I wanted the text to feel like a collection of fragments, similar to the video segments. I was also thinking a lot about the way meaning is created through juxtaposition, and calling into question the extent to which we can read images like text and text like images.

soon our bodies will be other buildings excerpt, two channel video, 2017

Vignettes ‘Marquee’ installation excerpt / Seattle, Washington, February 2017

When Something Passes

A conversation between Gretchen Frances Bennett & MKNZ

Derelict, you’re not coming back, I mean that in the nicest way, rest almost sounds like a bittersweet parting note to Vignettes as we know it. And we know it most intimately in Sierra Stinson’s one bedroom apartment on the 4th floor of El Capitan. The series of one-night shows in this space came to an end on the night of Gretchen Bennett’s opening.

We pack ourselves in the unit one last time, surrounded by the chirping of Bennett’s quiet drawings, xerox copies, and sentimental ephemera; all tacked sweetly to the walls, high and low, like little clues to a lush and secretive life. In the mix, there are faint portraits, including a large, faded xerox drawing of Angela Davis, with starburst creases, like something found and kept in the box of all your priceless notes from the past. In fact, the whole show feels that way; little treasures more important for them to be touched, moved around, repinned, carried in a pocket, to feel the full life of their influence. This feeling reverberates off the wall, when Gretchen reads aloud a poem that accompanies the show, breathing clues of their significance into the room.

In this moment, I am taken back to fall of 2004, to when Sierra and I (18 and 17 years old, respectively) were meeting for the first time in Gretchen’s Foundations class at Cornish College of the Arts. It was her first time teaching at the college, and it was our very first class. She would read passages from other artists, critics, scholars, and poets, to us in the mornings. With my head usually buzzing from the anxiety of living in a new city, I remember feeling soothed then, as I do now, 13 years later. I never would have thought that I would be interviewing her today about a show curated by Sierra. But Gretchen always held us as peers, rather than students, so perhaps this is her prophecy fulfilled; or perhaps we all stayed here, in part, to hold one another up; either way I’m grateful.

MKNZ: I love a good title and this show has a great title. Can you elaborate a little on the origin of this text?

Gretchen: So the title, “Derelict, you’re not coming back, I mean that in the nicest way, rest” is in haiku form. And as I understand haiku, it’s giving great credence to a moment; letting the every-day be holy. And I love that. I wanted to talk about my inability to make objects; to face my inability to make objects. And I guess that is because, when my parents passed away, the objects from their house that I had lived with were suddenly gone. And that makes sense, of course, but now I have empirical knowledge of it and it just stopped me for a while. So, in order to start making objects again, I had to talk about the ones that stay with me, the ones that are beloved. They give me courage. And those happened to be the objects that were closest to me in my studio.

While I was exhuming these objects, I was also asking them to go away forever, in a sense. The word “derelict” is also a word for the objects that you throw overboard a ship when it is listing and you don’t want it to sink. Unlike “jetsam”, “lagan”, or other maritime words used to describe objects thrown from a ship, “derelict” are the objects you have no hope to ever see again.

M: Do you think that in the process of bringing these objects into the light for other people to observe was a process of you letting them go?

G: Yes. Definitely. Sometimes literally when they are purchased and go away. And it’s also letting go in a way that’s equivalent to acceptance. Things were kind of falling apart, disintegrating, and, with the promise of reforming later, I had to let them drift.

I was letting go of expectations as well. I was letting go of my persona as an artist. I actually think maybe I don’t have that persona anymore… yeah, I let that go.

M: That’s scary.

G: Yes. It doesn’t mean I don’t perform that persona sometimes, but when I’m performing it’s so my voice can come in louder, literally. It feels different. It feels like I’m being more myself in that moment. So yeah, the show is letting go of some things and claiming others. Maybe these objects are a threshold.

“Another Very Small Universe,” rag rug made from braided repurposed clothing from the artist and her father.

M: I think sometimes we can imbue objects with a lot of meaning when we are alone with them for a long time. Sometimes letting other people see them that does this thing where it takes the air out of them a little bit. I can become so superstitious about an object, to the point where it becomes really one-dimensional. And maybe letting it out into the world can allow other people to put their own projections onto it, which makes it a little less your own, but maybe less scary.

G: Yes. When someone recognizes something to the point of wanting to take it home, it’s such a relief to me.

M: There is a lack of preciousness to the way you chose to exhibit these drawings. They are so delicate and fragile, but also folded, crinkled, or fingerprinted in places. This give them a feeling of age, of temporality.

G: It’s interesting, right away sometimes I say that I don’t like something, that I don’t want something, and it’s a build up to wanting it or liking it. Today in the studio on my List Of Problems, I wrote, “I’m not creating drawings to comment on the act of drawing, sorry”. Both laugh. I was looking at how the photocopier draws and I wanted to collaborate with that machine, and I really became attached to the aesthetic of those shifting greys and the way they slide across the paper. I would draw in response to that relationship for a lot of the pieces. And I guess that is commentary on What Is Drawing.

I think the folding, too – I had this brief conversation with Tim Cross about how a photocopy can be a real material, and that’s how you keep those objects, by folding them. And the folds on the Angela Davis piece are this radiating starburst shape, I like that. I have this feeling that archiving is futile. Maybe that’s an adolescent thought.

M: I think that’s the mature thought. The way that you’re talking about treating these drawings sounds like performance to me. You have to let go of the idea of archiving things to make a really present performance. And they sort of share that quality. You can tell that they have a lifespan, you can tell that they are going to whither away. I feel that there is something undervalued about storytelling; sharing the idea or memory of something rather than the physical thing. That’s when you start to build mythology, you know? When something passes.

G: Oh that’s nice, I love that, “when something passes”. And passes is the perfect language for this body of work. Its an intersection for many meanings. I want to keep thinking about what archival is when I use that word.

There are artists I was paying homage to, like Vija Celmins repeating the rocks as an action of devotion. Mine were very off-hand, or deliberate to seem off-hand. And then I was thinking of Morandi, whose objects are always just coming into the light. Those all feel like they fit into the idea of the temporary. If I bring them into my studio practice, I’m letting them live even more. That’s an action of wanting something to last.

“Ruby Beach Honeymoon Rocks” Found stones. 14″ W.

“Ripple Effect.” gathered unaltered, arranged sticks from PNW tree varieties. 24″ W.

M: In your footnotes, you state “The Angela Davis drawing holds the room, just as it’s been a ballast in my studio. Many of these works are created between the photocopy and I, both of us drawing”. This is a very beautiful and relatable sentiment to me. And feels even more powerful, when standing in the room anchored by the starburst folded Angela Davis drawing, and immediately across the room is the giant, “Vesna is Spring, Venus is Venus” of you as a child, sheepishly front and center in an urban Slovakian landscape. What is the dialogue between the two pieces?

G: It started out as a historical fact and alignment of events. I started thinking about a childhood trip that happened in 1972 when I went to Eastern Europe with my family. And I started remembering that I was greatly affected by certain world events, even though not directly. Angela Davis is one of those events, along with the build up to Watergate, the Vietnam war. In that year Angela Davis was freed from jail and taken off Nixon’s most wanted list. And I saw her in the context of European publications, where her image was the only thing legible to me. So that’s where it started. And also because her image is so relevant, but her image and her person are two different things. And, how humbly for me, I have to understand that she’s walking among us. So she’s opposite this photo drawing of me when I was 12, while my self image was just forming. This was when I was forming my cultural and creative sensibilities.

M: Your poem, “A blue that keeps moving” accompanies this show. It chronicles the day you broke your knee at the beach, and the spreading of your parents’ ashes. I am reminded of Maggie Carson Romano’s show at Glassbox, with her text recalling her accident in the ocean, and the quiet pieces of her show holding a tremendous gravity as evidence to her survival and recovery after the fact. Do the pieces of this show serve as a kind of “evidence” for you?

G: I think it’s interesting to think of it alongside Maggie’s show. A lot of those choices on my part were intuitive and I just trusted that they were poetic both with the objects and with the words; in that way that poetic space is elastic. I think heavy stories sometimes need to be talked about lightly, so that you can talk about them at all…and talk about many things that you might not know you need to talk about. So I approached it in a more meandering way and ended up presenting a constellation of objects up against really substantial words.

So I would say that yes these objects are evidence for me, but that they needed to be light.

Like talking about the weather, when I really mean my knee.

M: It reminds me of the feeling of existing in the reverb of something traumatic happening. You can fixate on something to ease your mind, which makes everything sort of dilate. When my mind is happy I’m not noticing every little thing. But then in the aftermath of a traumatic event, I can obsess over an object, and it could be anything, and then it becomes precious.

G: The object becomes a place for memory to reside.

Graphite pencil drawing on Japanese screen paper. 38″H X 72″ W. “Vesna is Spring, Venus is Venus,” a self-portrait, drawn from a 35mm slide of the artist as a 12-year-old on a seminal trip to live in Czechoslovakia.

“Windfall Alphabet (extra-lingual version),” which appropriates found fallen twig materials, in this case an extra-lingual fir font, into a human lexicon: from the order of the tree to the order of language, letters, sentence and sign.

“Garland” Color pencil drawing on hand-cut paper, tracing objects on the frontier of existence. 16″ H.

“Oregon Grape” Color pencil drawing on hand-cut paper, tracing objects on the frontier of existence. 14″ H.

Photocopy and color pencil drawings on paper, tracing objects on the frontier of existence. 11″ W. “Obama, Smoking.”

“tru truth” Photocopy and color pencil drawings on paper, tracing objects on the frontier of existence. 11″ W.

Exported: Ariel Herwitz – Marble House Project, Dorset, Vermont

Text and Photos by Ariel Herwitz

Vermont holds a special place in my heart. And returning there for the residency at Marble House Project, now in its fourth year, I was struck by the green, the lush rolling hills, the tall wild grasses and the green tint of long unused marble quarries. The residency is housed on a defunct marble quarry in a large house clad in white Danby Marble, with formal spring-fed gardens based on those originally built during the Renaissance, and amongst many outbuildings. The Marble House Project hosts up to 9 residents at a time – some visual and performing artists, as well as writers, musicians, curators, and a newly instated Chef residency – in several sessions per summer. Residents live and work on the “campus” with small private studios, have focused time for their art along with working in the gardens, weekly events open to the public, and cooking and eating with the other session residents.

MAKING WORK:

I tend towards making swift work, with long periods of quiet, and then long periods of preparation, with a burst of energy in the studio. A three-week residency, though it seems relatively short, should be plenty of time for me to create a body of work. But despite what I believed to be ample time, in a region in which I am somewhat familiar, I had quite a struggle finding a rhythm. There seemed too much to be distracted by, and so much to look at and wonder about.

As I labored through different dying processes, finding as much time as I could between rain clouds to dry the yarn, I made myself slow down and think about process. I thought about endings and beginnings and how sometimes we don’t have the answers and we can’t find the correct paths, and I hoped that was ok. I hoped that getting away from my studio to restart and refresh was allowed to feel like this. That it was acceptable to struggle.

As I began to move through the work, I utilized any sunny days to work outside. It was important to me to feel a part of the landscape, even if the work I made would ultimately be inside, and removed from this location. In this way, the act of making the work, made it indelibly part of the experience of place.

Moving back and forth between my studio and the greater campus of Marble House, I experienced the solitary moments, the still moments, the moments of closing inward. Outside, the space was vast, though I was still generally alone, the space was open and full. This expansion and contraction is strongly associated with my work and process. The building of large open forms, with the eventual breaking down of shape and line. Bringing the works inside, also brought the memory of the outside, in. It gave the works the markings of dirt and grass.

The completion of the work involved a literal balancing act. Each day for three days, I set up the work, went to sleep for the night, and returned to find the piece in a jumble on the ground. This process of repetition, of creating something new from the same bones, helped me to see the work in a new way. The process, though similar to what I’ve done in the past, had a real direct relationship to the struggle to make work that I was feeling everyday.

I’ve been back in my home studio for about a week now, unpacking the work shipped from Vermont, and again beginning the process of making new form from existing lines. I feel energized and excited after the somewhat stressful three-weeks away. But certainly, there is so much generated in that struggle to find shape.

Left to Right: Joseph Brent (musician), Amanda Szeglowski (composer and dancer, Artistic Director of Cakeface), me!, Emma Heaney (author, The New Woman: Literary Modernism, Queer Theory, and the Trans Feminine Allegory), Daniel Greenberg (printmaker, sculptor), Janna Dyk (curator and artist), Devin Farrand (painter and sculptor), Tobaron Waxman (multidisciplinary)

Thanks Ariel! See more of Ariel Herwitz’ work at her website: http://ariel.herwitz.com/

Ariel Herwitz (b.1983 Atlanta, GA.) lives and works in Los Angeles, CA. She earned a B.A. in Visual Art from Bennington College in 2006, and an M.F.A. from Cranbrook Academy of Art in 2011. Her work has been exhibited throughout Los Angeles at Marine Projects, Loudhailer Gallery, Greene Exhibitions, and Ambach and Rice. She completed her first solo exhibition last fall at Ochi Projects. Her works explore through form, composition, color and texture, ideas of interpretation, understanding, and the subjectivity of the view or gaze.

EXPORTED: Ruth Marie Tomlinson – Two Dot, Montana

Parenthesis

Each summer I leave the city and all of its abundance: museums and movie houses, bakeries and sushi, lush green and the nearby ocean. I leave the comfort of my dear family and friends, trading it all for seemingly empty miles and the rural town of Two Dot, Montana where I’ve established my studio in a decommissioned schoolhouse with more rooms than I need. My husband John comes and goes throughout the summer, as do visiting artists, but I also spend time alone. Birds, clouds and books are my company. In the summer of 2015, Rebecca Solnit’s The Faraway Nearby became a daily companion. Solnit’s words and the summer itself explored the territory of transition, a place of longing and desire, a place of having and not having at the same time.

alone in the open

Just before the crickets quiet themselves the sun appears at the horizon and the birds begin to sing… a fleeting duet. Shadowy places are disappearing but heat is not yet rising with the sun. In this hovering between night and day there is a moment that stitches together darkness and light, sleeping and waking, dreaming and doing.

John is about to leave, once again, for our other home and I will stay. I already feel myself entering into a shifting place where alone and together are both present. I know I will soon question why I have stayed, but I wondered if I can briefly hold the place in-between when both realities are sharply clear and neither fully grasped.

Since October of 1971, I have shared my bed. John and I met on a weeklong campout in the Blue Mountains, crawling into the same sleeping bag that first night. I remember the feel of his pajamas against my legs, the cotton fiber worn soft. My slim dorm room mattress was our next bed and then a flabby waterbed in the living room of someone else’s apartment where we slept under the same sleeping bag we’d shared in the mountains. Later, still 18 years old, we slept in a yellow steel framed double bed in an old farmhouse full of college students who were learning more by making a life away from their parents than from the classes they were taking. We left that communal life for another bed on the ground in a canvas tipi. We’d sold all of our records and my dulcimer to raise the one hundred dollar price of a mail order kit. We stitched the pieces together and everyone thought we were brave. A lot of time was spent lying on that bed on the ground in the tipi, staying low and out of the perpetual smoke and gradually learning the reason North West Costal Tribes did not prefer this habitat of the plains. Was this our first brush with desire for a dryer more vast landscape, or just the foolishness of young love?

The place we’ve bedded down has changed and changed and changed, sometimes lasting a night, other times years. The most radical move may be the most recent; not a move exactly but a pattern of repeated migration from Montana prairie to the Washington coast and back again made radical by virtue of the journey not always being made together. There is nothing of our shared bed I wish to escape, but the desire for occasional solitude seems to necessitate it.

After taking John to the airport, the 2-hour return drive through the vastness of the eastern edge of the Rockies has nothing to recommend it. I usually love this drive but today I am asking myself why I choose this barrenness. Why do I choose to be alone? The questions I knew would come are raw and real.

On this first day, in the schoolhouse, in my “room of one’s own” even the sun refuses to show itself. I had thought of calling John, but there is a catch in my throat that I don’t want to release, so I sit still in the kitchen, held by the familiar green Naugahyde of the dinette chair rescued from my childhood. Later, walking past our bed I cannot imagine getting into it. I am the only one generating sounds and I have completely forgotten how to be alone. The minutes tick off and the night looms large.

Ultimately, I find myself occupying a slender strip on one side of our mattress, the rest neat and empty. His absence is tangible. Lying very quietly, I remind myself of my desire for solitude, of my belief that to be alone with yourself is to know yourself. And I remember Solnit’s reference to the story of Frankenstein suggesting that to not know yourself is dangerous.

My childhood closet in the house my father built was small and cedar lined. It smelled dense like the evergreen state itself. At the bottom of the closet with tiny dresses and sweaters made by my mother hanging overhead, was a square toy box painted deep red. I remember little of what was in that box, but I do remember emptying it of its contents and crawling inside. I may have even closed the closet door. It was not a hiding place. It was merely my own place.

It has taken decades to really see central Montana, though I have been visiting all of my life. I never disliked it, there was the novelty of the ranch and the cousins and my Aunt Carol who was like my mother but smelled of cottonwoods, slightly sour milk, and wood smoke. My father loved to hunt with these cousins and my mother loved to be with her sister. I sometimes went to school with my Aunt Carol where she was a teacher. While I fondly remembered each trip by its events I never thought of the landscape. It existed in the barrenness of my mother’s Montana color photographs of “scenery” taken in the 1950’s and 60’s. Had the colors faded? Were they just the product of the technology of the era? Or had I not yet been able to understand the palette of Montana? Back in our Washington home, I always quickly turned the pages of our family photo album past those muted rectangles looking for pictures of people. I couldn’t find anything in the rectangles of muted color and openness. I might have called it bleak, if the word had been in my childish vocabulary. But now, 50 some years later, I have chosen this landscape, one that I call barren only in my impatience. Any eager looking for something more is similar to the impulse to fill quiet spaces in conversation, not recognizing them for what they are.

Solnit recounts falling in love with a particular place and throwing herself into its vastness whenever she could. I’ve begun to feel myself falling into the open spaces of this place that lies between the curved parentheses of one mountain range and another on either side of the prairie. It remains critical to me to see those curves, to be held by them so as not to fall forever. I’ve heard of places like Kansas and Iowa where nothing holds the openness. A fall into the depth of such a place might be never ending. But I only imagine it, never having been there, always clinging to the sight of not so distant foothills that comfortably hold the space between.

The schoolhouse windows open onto the landscape; six portals in each room. Each square equals a dash of horizon, each dash part of the view out. It is a place of looking where eventually I can become calm enough to look at the same scene over and over each day.

I am sleeping diagonally in our bed now, a luxury of being on my own that doesn’t quite make up for the missing, but it is possible to hold both at once. This morning I woke with sun streaming into the windows and remembering my dreams, couldn’t imagine being anywhere else. I’d dreamt of stitching embroidery on gauze as flimsy as the clouds in the sky and of capturing the light on the floor and holding it… this is a beginning. Perhaps the missing can fuel rather than consume.

work and light

The plant life and wind turbines rest completely still. Sitting outside for nearly an hour, I cannot find a leaf or blade of grass moving. First I watch with a focused stare for the tiniest motion, then I look away and turn back quickly, as if to catch a thief sneaking. Finally the smallest movement of air ruffles the tallest blades of grass and I am ridiculously elated. Then suddenly a burst of feathered wings shoots out from behind my chair. A juvenile robin… had it been there all along? Feathers are so light and airy, but when propelled by a living bird, the sound is a deep and resonant thumping. How did birds come to symbolize peace and lightness? Perhaps only by being viewed from a distance, soaring gracefully. Close at hand they are busy creatures, pecking and squabbling and claiming territory.

Sitting in the yard again, I watch two rabbits search out specific blades in over an acre of grass. Their darting around is fairly random, but looks similar to my days in the studio, moving back and forth without apparent logic from one project to the next.

…if you diligently work from nature without saying to yourself before hand – ‘I want to do this or that,’ if you work as if you were making a pair of shoes without artistic preoccupations, you will not always do well, but the days you least expect it, you will find a subject which holds its own with the work of those who have gone before. You learn to know a country, which is basically quite different from what it first appears…It is the experience and the poor work of everyday, which alone will ripen in the long run and allow one to do something truer and more complete. – Van Gogh November 1889

In strong light, my neighbor’s field changes throughout the day. Early mornings, flooded from the side by a low sun, it is nearly white. By high noon it is ripe with yellow and in the evening dusk it looks green like all the grass around it. Van Gogh relentlessly put to the page whatever light condition was within his field of vision even when it was the view from the asylum window.

In the far north, where days or nights can be very long depending on the season, Solnit finds the days disorienting and difficult. She believes ideas emerge from darkness, from the edges and shadows, the light only providing a place for them to be seen.

Light and darkness… in rural Montana I live by the transitions from one to the other. Is it the sun dropping behind the western hills in a preposterous brilliant pallet that causes me to step outside and register the move toward night? Or is this just the marker of a time for gathering in, for reducing the vastness of space to the clutch of four walls and a reading light? And is it the new light that makes early morning a time of alertness? Or is it having just come from the darkness of night… a time of rest and perspective?

I see the sun coming through two slits at the horizon, first a luminous pink light and second a brilliant white. Each lasts a few minutes before the sun is behind a band of dark clouds. It is not the color but the constant game between sun and clouds and my need of bright light for drawing that keeps me watching the sky. I sit on the porch waiting, at first I needed a sweater, then not, then I needed it again… seven and a half weeks here in Two Dot…. not enough…. too much.

It is toward the end of my separation from John, I woke up feeling, not blue, but a little choked, perhaps with both joy and sadness. Is it the two gin and tonics drunk last night before at the bar laughing with friends? Is it the sun shafts through the few clouds at the horizon in rays that make some think of god? Or is it waking in this big bed alone on this day that marks 43 years with John? A few minutes together on the phone when we wake and again before we sleep has sustained us, but I am ready to feel his arms around me, to close the gap between the faraway and the nearby.

Deep in the night before quitting Two Dot for a week in the city, the stars have woken me. They have been behind cloud-cover for days. But now, less than four hours before I am to leave, every possible star has come into view. They entered the house and my sleeping fog, opening my eyelids gently but with determination. And so, I’ve made my way to the porch. The Milky Way arches over the house and every brilliant point is a goodbye and an invitation to hurry my return.

there becomes here again

Solnit imagines that the whiteness of a page before it is written on and after it is erased is and is not the same thing, just as the silence before and after a word is spoken is and is not the same.

After a week away with John I arrived back at the schoolhouse late, it was cold and dark. There were no stars visible, but the air was full of the now comfortable question, “What am I doing here alone?” I am coming to recognize this as a transition question, a kind of semi-colon offering a chance to catch breath without laboring the thought of what is being conjoined.

This morning I am sitting in front of waves of prairie, the Big Belt Mountains hovering in the distance. It smells of grass and dirt. Not that long ago I sat in front of an expanse of sea that rocked in front of the Olympic Mountains, smelling of seaweed and salt. Back and forth, back and forth, there becoming here and then there again.

Cable Griffith + Josh Poehlein on ‘The Three Freedoms’

A discussion between Cable Griffith and Josh Poehlein regarding his recent Vignettes Marquee

Note: Best viewed using headphones or external speakers.

Cable Griffith: Let’s try to end at the beginning and see what happens. So let’s begin in the future. You just completed your video project The Three Freedoms. What’s coming up for you this spring and summer?

Josh Poehlein: Haha oh man, the future is… uncertain? I run a small exhibition space out of my garage in Greenwood called SAD Gallery, and it’s finally getting warm/dry enough to start thinking about upcoming shows. I have a date set for the next exhibition, but it’s not totally official yet. I also really want to do something for/with Forrest Perrine’s “Outer Space” series where artists exhibit in non-traditional/non-art spaces. We are looking at spaces and possibilities at the moment, but again nothing is nailed down.

In terms of moving forward from this piece I feel like I’m pulling threads in a way; like trying to use the end of one piece as the beginning of another. I come from a really project/series based background, and I’m trying to both honor and move beyond that. I have some ideas that involve the moving image which are directly related to this piece, and I am also exploring still-life photography that I think shares similar concerns with The Three Freedoms regarding illusion/immersion/fiction. I exhibited some early attempts at this sort of thing at SOIL Gallery in November and want to move forward in that regard.

CG: So how did SAD Gallery come about? What are your goals for the space, and how do you decide on what artwork and artists to exhibit there?

JP: SAD Gallery was something I had in mind before even moving to Seattle, in fact I think I bought the domain for it while I was still living in Chicago for grad school. People kept telling my girlfriend (now fiancée!) and I that we were going to get Seasonal Affective Disorder, so that’s sort of where the name came from. It was wishful thinking for a while until we ended up renting a place with a garage and I was able to build out the space. The space acts as a literal garage, my studio, and it transforms into the gallery a couple times a year.

My goals for the space have always revolved around connection, which means connecting with new PCNW-based artists and re-connecting with artists and friends from the past. So far there have been three shows, and each one has been a 2-person exhibition which pairs work from someone I know pretty well with work from someone that I have met out here. The plan is to continue in this mode for the foreseeable future, trying to find more interesting combinations of work while forging new relationships and connections in the area.

CG: How do you see the gallery space as an extension of your own practice?

JP: To be honest with you I actually didn’t see it that way at first. My initial thought was that it would be a good way to meet people in a city I am new to; a way to get involved in the arts community without being enrolled in school or working in a museum or gallery. Recently though I have been thinking about how my work has been influenced by the space. The process has made me look deeply at work I thought I knew well, and to approach art I am unfamiliar with in a different light. I feel like all the shows have taught me a lot about installation and reception of work, and that bleeds over into decisions I am making about my own practice.

CG: In your own artwork, what attracts you to working in terms of a project or series?

JP: I’ve been struggling with this a bit recently, trying to define what I do and what I am attracted to and why. I think there are threads that run throughout my work, but distilling them into something concise has been a struggle. I know I have always had an attraction to fiction, science-fiction specifically, but also just the ability of a work to transport you somewhere impossible, maybe “magical” if that’s not too cheesy of a term. Previously I have done projects that, in a sense, sought to create these fictional worlds; looking into the past, documents from an imaginary disaster, a first-contact story, etc. With The Three Freedoms there is that thread, there is a possibility of falling into the piece, but it’s also analytical in a way, trying to work out what the impossible looks like, how do we depict it?

CG: Is there something in particular about working in a series that feels limiting? Why do you feel compelled to work beyond that?

JP: First of all, I think there is value in working in a series, in developing a long-term body of work, and I am interested in continuing to do that sort of work in the future. That being said, a lot of times when you are working on something like that, your little sketch ideas get put to the side. Like I have this idea, probably ingrained from 7 years of photo-school, that you have to have 20+ finished pieces, all framed the same way and displayed in a group, and that is what a body of work is. But then where does this video piece go in that? And do I now have to make more video pieces to go with this one? I mean obviously the answer is “no”, haha, I’m not doing this for a client, and I make zero money on all of this, but I do struggle with these questions!

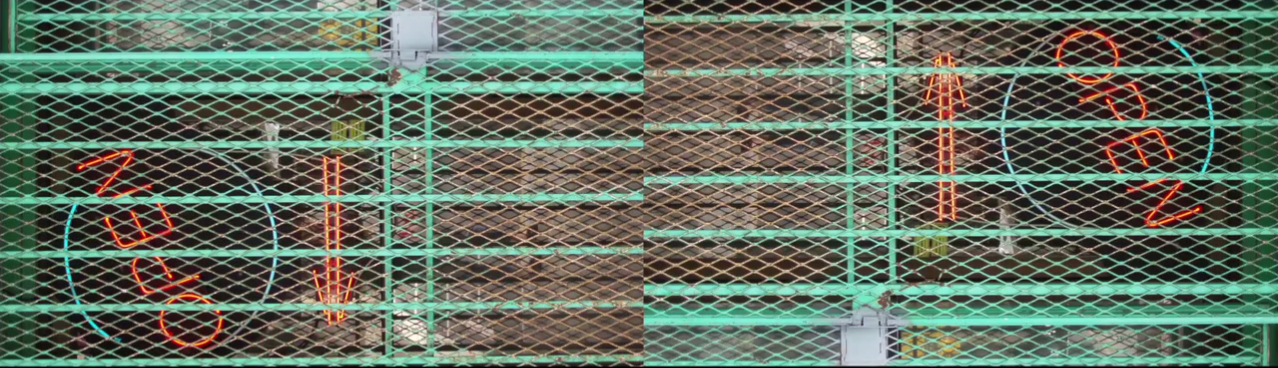

CG: I’ve experienced the video piece both as a stand-alone video online (with headphones), and as a public installation, via Vignettes. When creating it, did you have an ideal location or format for experiencing it?

JP: That’s an interesting question, sort of wondering if there is an “ideal” version of the piece, or if it can inhabit multiple spaces/iterations. I had the idea for the video for a while, and when Serrah approached me about working with Vignettes, I used that as a reason to bring it to fruition. We got in touch with Common Area Maintenance and they were down to host the opening/viewing. So there isn’t necessarily a perfect place for it, although it’s kind of funny you ask because I almost don’t even want to call it “finished”.

I know for a fact that there a lot of examples of the type of footage that I was looking for that are still out there, but there were time and monetary restraints that meant stopping at the point the piece is at now. Ideally I would pull from the film-prints of the films I am appropriating from and the master files of the tv shows, and have access to like all of Scarecrow’s database, and a team of people scouring through obscure made for tv-movies and foreign sci-fi films, and just have something that is ridiculously long, almost unwatchable all the way through, haha.

CG: It’s exciting to know of a growing number of independent, artist-created spaces around Seattle. For artists, this would seem to offer more chances to work with and to respond to interesting and new kinds of locations. Also, it’s nice to think that artists and artwork can connect maybe more directly to communities in different ways. Do you have any dream locations to work in or respond to?

JP: Yeah, I have been interested in DIY spaces for a while. Some of the best shows I saw while living in Chicago were in spaces that were not initially intended for art display. I’m pretty sure I have been to all of the less-official spaces in Seattle, and it’s exciting to see new ones pop-up as well. I would like to have shows a bit more consistently at SAD but weather plays a role, and I also use the space as my studio.

I really like the Glassbox space, and I have seen a couple shows at Two-Shelves that I thought were really cool (Max Kraushaar in particular), but I’m not sure if they are still having events there. I have some specific architectural elements I want to work with; a freestanding wall in a space, a lit and unlit room in the same space/building. Essentially anywhere with some subdivided spaces or a space that can be built out that way is something I’m interested in working with.

CG: I like to think of how an artwork has the potential to both transport you someplace else and keep you very much in the present at the same time. In terms of science-fiction, would you parallel art’s transportive power with a portal?

JP: Whoo, haha, this is a complicated one. I have been increasingly interested in exactly what you’re talking about here! I come from a photographic background, so the metaphor of art as window or portal is really strong in my mind.

Recently, I have been asking myself whether something can be an image and an object at the same time. To return to the photograph, do you have to mentally pull yourself out of the ‘image’ to consider the piece as an ‘object’ (the print surface, the mounting technique, the size, etc.), or can you hold both in your mind simultaneously? And furthermore, is there a difference when something is abstract vs. recognizable or figurative?

CG: That flux between the image and object is really interesting to me as well. I love thinking about how an object can ride the line between shouting its physical attributes while simultaneously vanishing all together, as a window.

JP: With The Three Freedoms, the predominant motion of the piece is pulling you inward. In the original film/shows the effects are meant to depict, quite-literally, portals, but since these things are inaccessible/unknowable to us, they are depicted using abstraction and usually a kind of one-point perspective. I was interested in what happens when those effects are pulled out of their narratives. When they are totally abstract, are they still immersive and transportive?

CG: I like how the piece transports me to a place of constant transportation. Sort of like being stuck in a wormhole. I get the sense that we’re being taken somewhere, but never know where the tunnel leads. But the journey is remarkable. I mean, what if you went through a crazy worm-hole through time and space, only to end up in your kitchen 10 minutes ago? Kind of anticlimactic.

Some might characterize science-fiction as escapism. Do you view it that way?

JP: Ummm, my short answer to this is ‘yes,’ but the genre is a large one, and to a certain degree all fiction is escapist. I am a legitimate fan of a wide range of science-fiction, from blockbuster hollywood films to lesser-known “hard” science-fiction stories and novels. I use the genre both to escape, and to engage on an intellectual level. The best stuff is all about the problems we encounter today anyway; identity, politics, how to build a sustainable future, how to understand those that are different from us, how to consider humanity from a different perspective, etc.

I think written science-fiction probably gets a bad rap because a lot of times the characters are pretty one-dimensional. In my mind, the world is the character, or the premise is the character, and the story is there more to show us around or give us a tour of the possibilities of this place. That’s not to say you can’t have complex characters and a complex world, but sometimes you have to read about a lone-wolf getting the girl and beating the bad guys to get a glimpse of something more interesting underneath.

I like the idea of taking an incredible journey just to end up back where you were. There is the cliché of “it’s not about the destination man”, but that actually holds true with this piece because there is none!

CG: I guess you could say that any artwork, song, or film, is something to get lost in for a while. I think we’re all after that to some degree. I mean, it’s exciting when something stops you in your tracks and completely captivates your attention from where it was a moment before. But if artwork has that power to ground you in a transportive state, then maybe it doesn’t seem so escapist?

JP: Hmm, yeah that’s an interesting point. I think it might have to do with intentionality or maybe criticality? I remember I saw Avatar in the theater when it first came out. It was the first 3-d movie I had ever seen, and I made a decision before I even went in to just fully let go. I knew from the previews that it was likely to be a “bad” movie, but I decided to treat it more like a roller-coaster than a “film.” It was totally escapist, I was consciously trying to keep critical thought at bay and just fall in. At the time, it totally worked. I really enjoyed the pure experience of escaping into this world, but I don’t even remember the film that well. I couldn’t discuss plot points, or dialogue, or any issues regarding its merits as a piece of art.

The thing I do remember though is that whole experience, how I really felt like I left this world for a bit. When I came out into the parking lot everything seemed a little dull, like I was disappointed that I was no longer flying around on another planet, fighting for true love and freedom. I was poking around online afterward and it turns out a lot of people felt that way. There were even “Post-Avatar Depression” groups popping up. I may have even talked to you about this at the opening? Haha, maybe not, I guess this was an important experience for me because it always comes up.

CG: You mentioned having 7 years of photo school under your belt. Do you remember what initially attracted you to the camera?

JP: Specifically I’m not sure what the initial attraction was. I was and always had been drawn to art classes and creativity, but I was also not super talented in terms of drawing, so maybe that was the attraction. The fact that I didn’t actually have to render something by hand to get it on paper was nice. I know I got my first “real” camera because my mom bought a Nikon SLR and she kept dropping it, and finally got frustrated and I inherited it. I think that camera is still around somewhere.

CG: How has your relationship to it changed since then?

JP: I think one of the main things is I rarely just go out and “shoot” like I used to. I actually miss that and want to start doing it again, but maybe just for the fun of it and to keep my eyes sharp. Over time it has become more and more about realizing a specific vision, be it in the studio, or out in the world. The photographic process for me has less chance than it used to. There is still discovery and little changes, but it’s rare that I make an image that I wasn’t already planning on making in some way.

The other thing that has changed is that I am now interested in making photographs, and work in general that is about the medium itself as much as it is about what it depicts. I want images that are about images, but also about something more than that. Still thinking about this one at the moment…

Exported: Eirik Johnson at Donkey Mill Art Center, Hawaii

Text and Photos by Eirik Johnson

Mauna Kea

This past February, I traveled to Holualoa, a small town in the coffee producing hills of the Big Island of Hawaii. I had been invited to participate as artist in residence at the Donkey Mill Art Center, a community arts space housed in an old farming cooperative. I arrived with broad stroke ideas for my residency, but my intention was to remain open and receptive to the place and those I met.

That notion of place was a recurring and connecting concept during my stay. Over meals and conversations with kupunas, elders from the community, I learned about the history of Holualoa; of families whose relatives had left impoverished Japan in the late 19 th Century under labor contract to work in the island’s sugar cane mills and later homestead small coffee farms in the volcanic hills of the region. I learned of the ghosts who wander subterranean lava tubes, bamboo forests and mountain ridges.

That connection with Holualoa’s past was given further context while working with a group of local teens with whom I collaborated on a series of photographic and video-based portraits. We looked at the history of portraiture in art, brainstormed visual memories, and worked together to compose and create works that connected back to my conversations with the kupunas.

Much of my residency was simply spent wandering and exploring, both in and around Holualoa, but also further afield. I watched the sunset from the Mauna Kea volcano, explored old movie theaters in Honokaa and Hawi, and discovered beach crab holes amidst tiny bits of plastic washed up from the Pacific Ocean Gyre.

During my residency, I stayed as a guest of Hiroki and Setsuko Morninoue. Both renowned artists, the Morinoues, together with their daughter Maki and her husband Geoff, were generous in aloha spirit, knowledge, and participation. Their eldest daughter Miho Morinoue helped facilitate my entire residency at the Donkey Mill and was pivotal in connecting me with the entire community.

Now, as I begin the work of looking back through photographs, editing video, and listening to audio files, I daydream of Holualoa and the smell of coffee blossoms.

Gekko

Film Still of Hiroki at the Coffee Farm

Althea with Rotten Fruit

Brunch with Kupunas

Coffee Blossoms

wisdom of the underworld

Essay by Ben Gannon | Photographs by Sierra Stinson

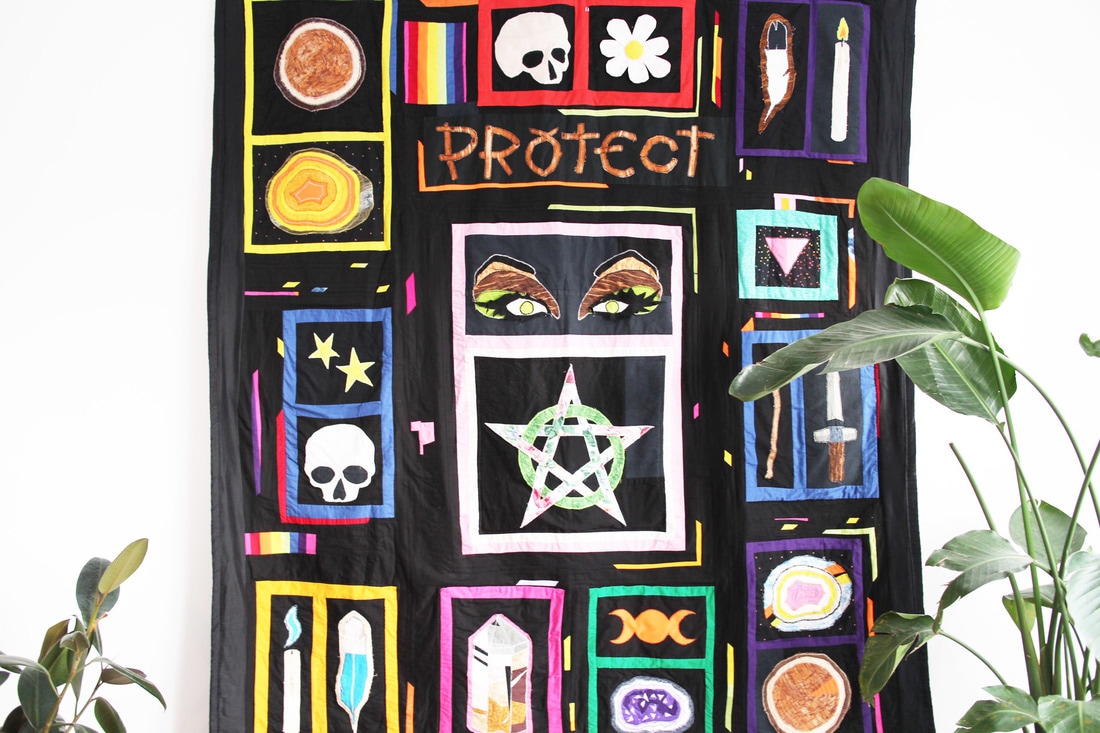

Arriving at Joey Veltkamp’s February 2017 Vignettes exhibit, it was clear from the street looking into Rachel and John’s house that this show was dealing with the supernatural. Hanging in the front room window were sheer fabric panels with appliqué patches of heavily shadowed and made-up eyes announced the other-worldliness. Spirits are present and in many forms. A haunted space, like all indoor spaces at the end of winter, so charged with telekinetic and telepathic energy of its occupant(s). A haunted house, but in January (unlike October) we are familiar with ghosts, and in the January of this year the powers of naked death ascended to the leadership of the world.

Once inside and in the first room of the show there hangs, along with the sheer panels, a large black quilt. It is composed of spells and talismans, each smaller square housing a symbol of power and protection, an anchor point from which to journey into darkness. Skulls, crystals, pentagrams, the word “protect” in appliquéd ‘wood’ letters—homage to Gretchen Frances Bennett’s found stick word art.

Sharing the space with the eyes and the spell quilt were a pair of pillows placed on chairs, each with a broken heart emoji, invoking the kind and tragic power of Laura Palmer, another symbol of strength and resistance. It becomes clear that wherever the journey of these artworks is headed, grounding in power is necessary and some danger is present or lies ahead.

In the next room more sheer panels hang in the windows and more eyes look out from the gauzy material. Along with the eyed panels there was a table full of small ceramic ghosts painted up like the cosmos and sitting on small, round mirror disks, the infinity of their motif reflecting into infinity. There is little distinction in Joey’s work between outer space and the underworld – vacuum and death both infinite and un-survivable phenomenon.

Binding this second room with the first was a pair of flags and a new motif for Joey’s work – a black cat appears on the flags, almost identical to each other—the latter done by memory, on opposite faces of a wall, each with the phrase Déjà Vu appearing on it, the lettering the same but the colors slightly different and the cat figure in slightly different positions. This diptych is a direct reference to the movie The Matrix, where the repeated sighting of the same black cat as an experience of deja vu is revealed to be an indicator that there has been a significant change made to the fabric of the world of the matrix. Not only a personification of the phenomena of change, the cat is our familiar and our guide while traveling through the dimensions.

Also hanging with the eyes, the cats, and the cosmic ghosts is one of three quilts of its kind in the show. Multi-tonal, textured blacks patched together, the chorus of darkness interrupted with flashes of heat and light in the form of randomly sized triangles, trapezoids, parallelograms and rhombuses of color. Two more of these burning landscapes hang on the walls leading up the stairs to the final room of the show. Akin to the blending of the underworld with outer space depicted with the ceramic ghosts, the landscapes depicted in these three quilts is both of the fire of space and the fires of hell. Accompanied by the indifferent harbinger in the form of the black cat, we are walking with Joey through the cosmic underworld.

The final space of the show, past the watching eyes and glittering ghosts and burning voids, is the bedroom upstairs. The sole artwork in the room is a quilt lying on the bed. The cats again appear; this time en masse and in distinctly different poses, on the quilt upstairs, the resident housecat Brigitte having found a comfortable spot for itself on the bed as well.

But what are the lessons from hell and the vacuum, of walking through this heartbreak simulation? Joey’s work participates strongly in the realm of the pop culture oracular, pulling in and manipulating the signs of culture of the moment, playing in their subtleties and shifting them around before casting them back in to the infinite sign constellation in the form of fabric objects with meanings made from Joey’s particular alchemy of working with sadness and elementally reconfiguring it into joy.

But all oracles have limits to their vision into the ocean of possibilities. And it is the brave or unprotected oracles that, in the midst of confusion, go deeper, towards the leveling wisdom of infinity and death, and the freedom brought forth from acknowledging that wisdom. In the face of the cruel madness and absurdity so evident in our world at this time, the reminder of our death is a reminder of our life. In the face of the infinite void of space, we are able to refocus on ourselves with a grounded perspective.

But it is not all grim contemplations of death and freedom and endless emptiness, and the cats in their various poses on the final quilt in the show remind us of that. With each change or glitch in the fabric of our worlds, with each appearance of the cat as a harbinger of change, there nonetheless remains the infinity of other worlds with other changes and glitches occurring all at once. If the wisdom to be gained from passing through hell and space is the infinite of the void, the wisdom to be gained from the multiplicity of black cats is the rich infinity of being, existence and possibility.

Andrew Lamb Schultz’s Salvaged Fantasies

Essay by Steven Dolan | Photographs by Sierra Stinson

Recently I found myself arguing the value of Andrew Lamb Schultz’s work with a friend. Their conceit: it’s cute (as if that is insufficient). BUT! I protested, doesn’t cuteness have transformative potential? Isn’t it possible to create work that is immediately satisfying for its surface level appeals to the flexing of our cheeks, that also does more should you so elect to live in a world where cuteness can be radical? “Cute” is certainly overused in my own vocabulary and can be invoked to infantilize and reduce people and actions to a pleasant passivity. Sensitivity to this is important, as is the context of its invocation.

Also important is recognizing that language is mutable, and that the terms of terms can be mutated and changed, queered beyond historically violent structures of power. Tracing the etymology of “cute,” one arrives first at acute, then variously: a needle, to sharpen, to arouse. “Cute” needn’t be regarded as exclusively slight. It’s cute when you hold your drunk friend’s hair back, it’s cute when strangers ask your pronouns, it’s cute when a bank is called to task for their support of unethical development, it’s cute when a neo-Nazi gets punched in the face and a proliferation of the video is accompanied by an exhaustive slew of soundtracks. Cuuute. Feel it.

Trust functions only if experienced mutually. Intention alone gets us very close to nowhere, but intentional listening is just as important as intentional speaking. Lamb invites you take in their work, saying this is glorious, this is beautiful, love this and I will show you the way to a better world.

In considering their show Eutopos / Utopos, one should note the ways in which this is a personally idealized, or at least preferred, space to exist in. In a world built for a few, the culling of what is affirming and nourishing to construct or restructure space is necessary for the survival of those on the margins. It is the queer imagination that takes these facets of a “good place” perhaps a safer space, in the hopes of achieving the impossible but still vital utopic place. It is essential to queer political imagination that there is impossibility.

In a conversation about their show, I confessed to Lamb that I had a sort of fantastic vision of their working process. One version of this imagined reality sees them in a minimal space that is more a spatial field than physical room. Meditative and serene, it’s an illuminated void where the artist has a kind of psychic communion with their ideas and channels that energy into work that is manifested with ease. I can only conclude that this sense comes from their images (and my own desires for work/art/love to be summoned on command), which has clung to me like a spectral dream.

This, of course, is not how Lamb works. They’ve described their practice to be compulsive, wherein doodling happens in the in-betweens: on work breaks, between day jobs, on the bus. Art work happens post-day job.

There is little time off. Much of the work created for the show was produced in an unorthodox studio space in a Capitol Hill basement, which could certainly be romanticized, but one resists. This show, like much of their work, nurtures with the proposal of a less chaotic world, a less demanding world; fantastic therapy that embraces the viewer with a sense of calm and affirmation: things could be different.

“A lot of the images and a lot of the drawings I make, are me depicting the daily life I want to be living that I’m not, and a lot of that is leisure,” Lamb told me. These dreamscapes are for their friends, their community, proletariats if you will. “It’s like meditations on Marxist ideology in a way.”

Lamb’s work opens a prismatic set of fantasies, some which feel within reach, and others that are seemingly impossible in nature. Such is the dichotomy of the show’s title.

“A lot of the images and a lot of the drawings I make,

are me depicting the daily life I want to be

living that I’m not, and a lot of that is leisure”

Lamb is an artist who creates a world, one with a particular vernacular that allows the viewer to consume the work as far as they choose to see in it. One can accept the sweet loveliness of the work on aesthetics alone, though its keener readings open greater dialogues around humanity and its relation to the world.

In Reclamation I (Mossy Ruins), Reclamation II (Mossy Nude), and Mossy Figure, the artist integrates plant life with human signifiers, whether they be built structures or figures themselves. Drawing on the architecture and sculpture of classical Greco-Roman antiquity, the supposed building blocks of Western civilization, they imagine the possibility of a human footprint becoming more enmeshed in nature. It is through natural interventions that signifiers of the violence of civilization are reclaimed. So-called development has been pacified and recycled for its aesthetic value.

Moss has been transformed into a delicately rendered system of multiples rather than a solitary blanketing substance, looking no less consuming. A departure in medium for the artist, Mossy Figure is a silk-screened soft sculpture. A pink figure embellished with bottle green faux fur and found artificial flowers sits atop a pedestal painted on all sides as if a column. Lamb’s hand is still ever-present as the planes of two dimensions cross over to three, a kind of trompe loeil play. Such an illusion is useful in understanding the way queer identities and genders are presented and perceived: what one sees may have a dissonant reality not visible to the obstinate eye.

A four-panel wooden screen painted over with mantises and orchids constitutes another departure for the artist. Here we have an aestheticized object, one rendered in soft pastels and tender crudity, that would most typically