A Complex Machine | The Work of Aidan Fitzgerald

Essay by Rich Smith | Photographs by Megumi Shauna Arai

Aidan Fitzgerald’s work ethic approaches insanity. So it’s no surprise that entering his studio apartment in Capitol Hill feels like that moment in the movie where the crazed inventor switches on his light to reveal a workshop bustling with perpetual motion machines and bubbling beakers.

In the apartment, art and parts of art lie everywhere. Half-finished abstract paintings lean up against the walls. Books splay out on the couch. His Risograph, a printing device that resembles a copy machine, rests against a wall. Even his records, turntable, and Nintendo 64 seem to be part of a project he’s got going on.

As Fitzgerald gives me the tour, he explains that he splits his apartment into three separate zones of work. A small, windowless room he calls “The Shed,” houses all his materials and tools. His kitchen table doubles as a drawing table, and he’s reserved the larger living room area for painting. When he decides to work on something, he simply walks into The Shed and selects a few tools that excite him. If he’s selected drawing tools, then he shuffles into the kitchen. A brush in his hand sends him to the living room.

Juggling so many projects at once didn’t used to be the norm for Fitzgerald. Back in 2011, when he was completing his B.F.A. at the University of Washington, he would focus all of his emotional and artistic energy into one, giant, project. At the time he was under the impression that the man-hours and rawness he put into each piece would somehow show through in the work. He describes a painting of great ambition, a big drawing of Freud and his daughter that he scraped up, drew over, and layered with paint for months and months. That painting now carpets the floor of The Shed.

“After a while I realized that if you keep whittling a log, eventually you’re gonna end up with a wood chip,” Fitzgerald says. “One day I looked around at my studio and thought ‘Gah, I have so many wood chips.’”

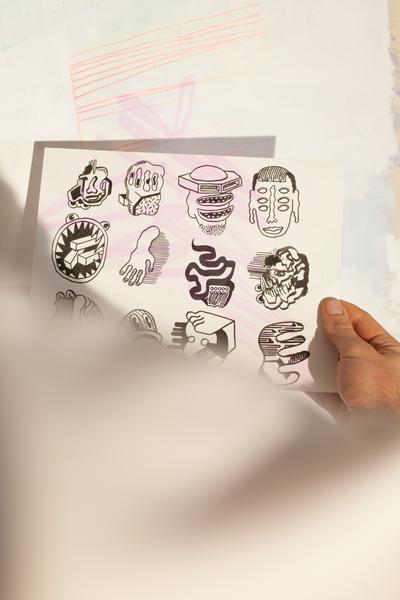

Enter the Risograph, the solver of the wood chip issue. The device, as Fitzgerald puts it, “is the funky little brother of the letterpess.” Like a photocopier, the machine scans an image and produces an ink copy, but the effect looks more like a screen print than a Xerox. To create a piece, Fitzgerald takes an image—a collage he’s constructed out of cut-up personal photos, say, or a drawing—and runs it through the machine. Now that he’s got several copies of the same image, he starts experimenting with different treatments. He’ll draw all over the image with a pencil. He’ll try paint. He’ll see what it looks like dipped in water. Because he has so many copies of an image he likes, he can whittle away as much as he wants and still have a log at the end of the day.

The Risograph also serves as an art-making tool in and of itself. He basically paints with the thing: “When the scanning light is moving, I move the image with it so that it warps and smudges the image,” Fitzgerald says. He used this process to create Neighborhood / Unwind, his piece for Vignettes Collection. The red part that looks like a broad brushstroke is actually a collage of different scenes he smudged together on the machine. He shows me three different treatments of that image: “I fiddled with some colored pencil. Then I drew a cartoon weasel and thought ‘Whaaaat? Why??’ Then I experimented with broad black lines and thought they worked. It’s a tornado. It’s a prison cell. It’s a landscape. It’s a radiator. It’s a cavern. It’s a gunstock.”

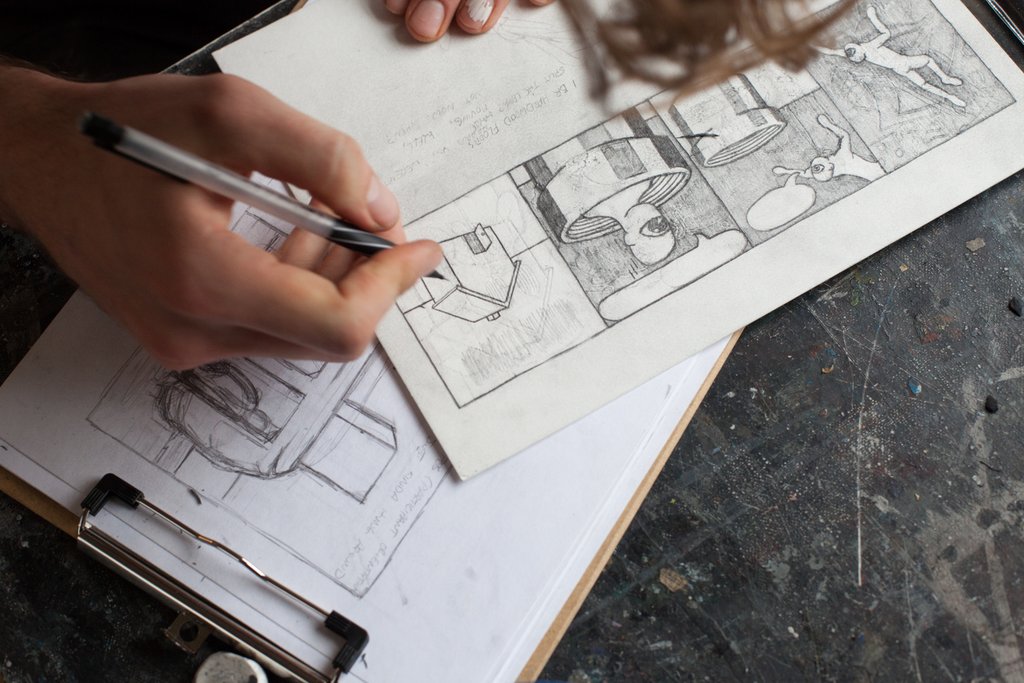

Fitzgerald also employs the Risograph to make his own short-run comics and books, all of which are informed by his early training in painting. Painting offers him a set of skills, impulses, and pleasures he uses to push against the strict constraints of comics.

“I don’t really make good comics. I’m not a cartoonist,” Fitzgerald is quick to say. “Most of the comics I do make are less comics and more like sequenced images. It’s less like you’re watching a movie and more like you’re sitting on the couch at 3 a.m. and you’re strung out, flipping through channels.”

His “lists,” a kind of comic strip / painting hybrid, evoke this channel-flipping mood. The lists are a number of disconnected, distinct drawings that use the same imagistic vocabulary. They look as if he went into a comic book, exploded it, and then gathered all the pieces and laid them all out into a line. Like a haiku, each drawing makes one “move.” In the case of a haiku a leaf might become a butterfly wing or a mountain might shrink in a dewdrop. In Fitzgerald’s drawings, a pattern will reveal itself or a juxtaposition will emerge and then at that moment he’ll abandon the piece, as a painter might, satisfied with having made a move he could feel.

His interest in poetry adds even more tools to his shed. In recent work, Fitzgerald takes poetic rhetorical devices such as anaphora and refrain and breaks them over the gridded rhythms of paneled comics. With this process he produces surreal-ish and lonely full-page compositions that repeat several images until a concrete feeling emerges.

In the future, he plans to sustain that lyrical play over the course of a much longer work called Tuesday in Othrwrld. Blending rhetorical techniques and skills from several different genres in order to create an epic lyric comic strikes me as bold, challenging, and potentially really fucking cool. One thing’s for sure: he’s got the tools and the gumption to do it.

Back to In the Studio