A community of feeling

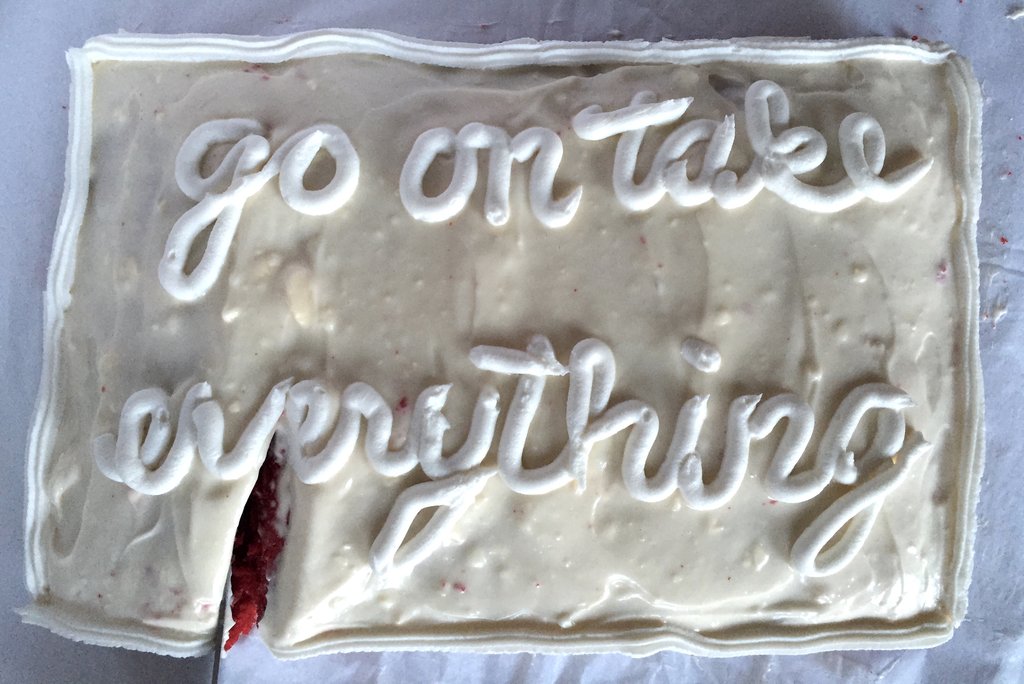

MKNZ and Erin Frost ‘go on take everything’ red velvet cake, frosting, 2015

Written by Steven Dolan

“It seems that we started with a deficit. And by the time we got to the show, we were in this major state of abundance, of surplus, which thematically tied into the show. You actually can take everything. We don’t need it anymore.”

MKNZ, Erin Frost, Leigh Riibe, and Sierra Stinson are spread out in the living room of Sierra’s apartment. MKNZ is describing the journey that culminated in the show “go on take everything,” marking the 5th anniversary of Vignettes. In a short expanse of time, the four artists and friends each found themselves left by their partners in the homes they shared. Over the course of these heartbreaks, the four women grew closer, further cultivating a nurturing web of relationships that gave birth to an interweaving of art practice.

Speaking with the artists, it’s clear that the emotional turmoil they experienced individually and cared for collectively, comes secondary to the new love and relationality that emerged. The show is more about their reverence for healing and the bounty that followed than about the pain they endured.

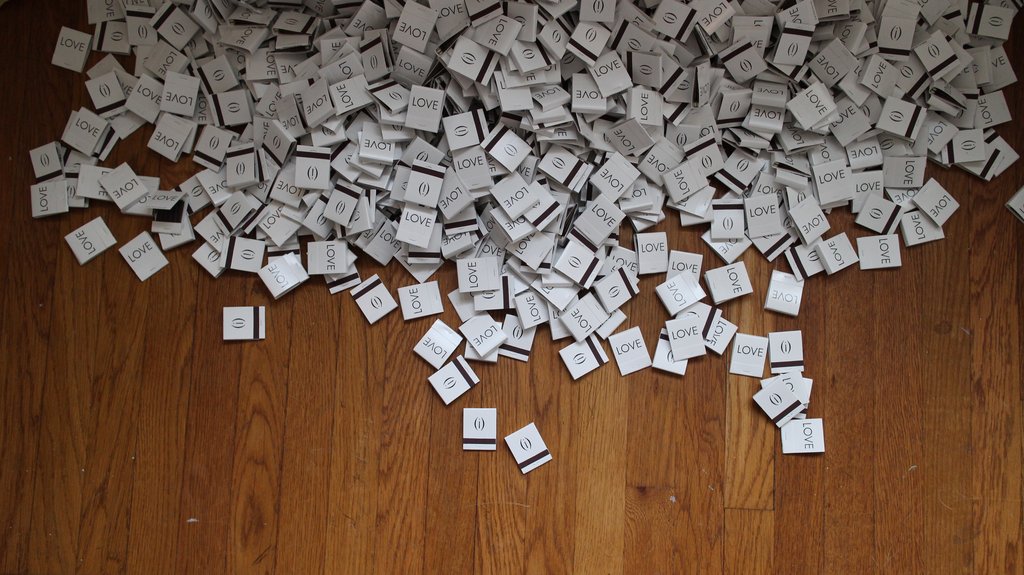

Leigh Riibe ‘Flammable’ Printed Matchbooks, 2015

The evening of the show, guests were greeted by a wall of Erin’s lipstick prints (“i want to lose them”) and other offerings, such as the red velvet cake by Erin and MKNZ that shared the show’s title and a pile of printed matchbooks by Leigh Riibe (“Flammable”). These pieces, composed of multiples that invited taking, constituting offerings of abundance. In giving freely to each other, the artists are equipped to share the loved they’ve reaped.

Wearing a wooden milkmaid’s yoke with two 45-pound salt blocks hanging from either side, MKNZ occupied the apartment’s bedroom, deprived of vision and most of her hearing. For the active two hours of the durational performance, she carried the weight of the salt blocks. Those that attended the show were invited to provide MKNZ aid by lifting the salt blocks in pairs, requiring the careful cooperation of those that stepped up. Anything less would offset her balance. Titled “The Inherent Codependency of the Heaving Heart,” the performance illustrates the kind of collective care taking that occurs in times of grief.

MKNZ ‘The Inherent Codependency of the Heaving Heart’ performance, 120 minutes, 2015

“It’s reminiscent to me of when you have a friend that’s really suffering and is kind of unreachable, in a dead-to-the-world sort of state,” MKNZ explained. “It takes a collaborative effort to care for that person. It can’t be one person’s job alone.”

Participants came in waves, gingerly taking up the weight, engaging in the tender ritual. A ring of viewers dotted the walls, observing the act, but also enveloping the performance in a network of symbiotic support and affirming energy.

The performance was not only a gesture of trust extended to MKNZ’s anonymous supporters, but also one of generosity. Individual identity was not relevant to this relation. Instead, it was predicated on the sheer fact of their shared existence. The burden of love is relevant to all of us, but it is up to us to answer its call.

Leigh Riibe ‘Letters to Leslie 1991-1997 (age 10-15), telephone, audio recordings, 2015

Tucked away in the bathroom sat a red telephone, with the words “I LOVE YOU” standing in the place of a number. When one answers, they hear Leigh Riibe reading letters she wrote to her sister Leslie from 1991-1997, between the ages of 10 and 15. Leslie kept these, gifting Leigh a binder of her side of their correspondence for her 30th birthday.

“My sister has always been the person that has seen me throughout my life,” Leigh said. “She’s been the one that listened to me when nobody else would fucking listen to me and pay attention to me when nobody else would pay attention to me.”

The letters detail everything from suburban ennui and adolescent existentialism (“I figured out today that I have no life.”) to appropriately dated cultural moments (“My neck? I can’t hold it up without it starting to vibrate because it’s so sore from headbanging to Nirvana’s Nevermind.”).

The Christmas lists alone illustrate a depth that culture rarely allows girls. Requests are at times endearingly specific (“Stuffed animal that has to do with snowy weather, such as a seal or Lamonts 1992 Christmas bear,” “Pink cat eye sunglasses with jewels in the corners at Hot Topic”), absurd (“Breakfast in bed for the rest of my life”), and brutally honest (“Don’t get rid of Stella, Clarence, Morris, or Stubby”—Leigh’s pets).

For as much humor as there is, one also hears Leigh’s despair. Demands to write back are a constant, suggesting an aching isolation. A particularly heavy letter sees Leigh predicting the death of a friend whose drug use has left her feeling helpless. Her narration of the past teems with feeling. She occasionally laughs, she invokes the gravity of adolescent anger and effervescent girlhood, and sometimes her voice quivers. In delving into these wounds and whatever other emotional remnants the letters mark for her, Leigh harvests an emotional abundance that is not tied to a specific time, for through the process, she is creating a future.

“I think the overarching theme for the show for myself was healing,” Leigh noted. “Talking and interacting with that time of my life without judgement and playfully was really healing.”

Erin Frost ‘that which has been your delight’ video still, 2015

Originally exhibited at Out of Sight, Erin’s “that which has been your delight” reaches a new intensity in conversation with her cohorts and the context of the show. Before the video’s creation, the death of a friend and her first love coincided within weeks. Having bought herself flowers after the first loss, she sat contemplating using the petals after the second, only to have them fall into her hand, sparking the piece that followed. One night swimming by moonlight, a friend, Adam Boehmer, put forth the phrase “making space for pleasure,” which became Erin’s mantra. “It just held me,” she explained.

The video begins with Erin face down on a bed of black fabric in a confrontational moment of grief. What follows is a sensuous exploration of feminine codes . We see a closeup of her sliding her arm through a sleeve of sheer, embroidered fabric and then slowly lifting the hem of her dress. Her hands dig into a visual field of flour. Milk glides down her nude body. Flowers are a near constant, even receiving their own milk bath.

What is achieved is not the masking of grief, but a cathartic moment of grief harnessed as pleasure. Erin taps these icons of femininity, articulating their potency and giving weight to beauty. She embodies a vision of emotional fecundity, illustrating the possibility of new life. Our culture teaches us to grieve quietly and conveniently, but her process rebukes that notion, instead choosing exhibitionism. Erin has no shame about her grief, nor her femininity, purveying and transforming these ideas as sources of power and strength.

“I think that when you’re feeling stripped when you lose things, you are faced with that power in yourself,” Erin suggested. “Everything falls away.”

Sierra Stinson ‘Two Vessels (Fill me up / Pour me out)’ 2 Channel Video still, 2015

In the kitchen, Sierra’s 2-channel video, “Two Vessels (Fill Me Up / Pour Me Out)” plays on a continuous loop. With a directness and simplicity, the video points at an essential emotional sensibility: one that not only externalizes or “pours,” but that also simultaneously internalizes or “absorbs.” One side of the video piece shows an amber-toned sponge taking in a steady drip, while the other demonstrates the mouth of a carafe pouring water. The shots are framed to focus on the actions, not the entirety of the objects themselves, nor the environment they exist in. In doing this, Sierra emphasizes a humble gesture that evokes clarity: perhaps it can be that simple to love and be loved.

“We are all vessels. I had that idea the week after I went through my breakup,” Sierra said. “I was like, oh, I’ve been this cup pouring out, pouring out, pouring out, to the point that I can’t do it anymore. And then I was like, I need to be the sponge. I want to be that. At first it was a negative outlook in ways, and then as I worked on it, I realized we can be both vessels always.”

It is through the realization of vulnerability and an active channel of loving that an emotional system as this can function and nurture the wellspring of love that we give and receive, the piece asserts.

As an exercise in vulnerability and an intersection of relation and creation, “go on take everything” realizes a radical form of artistic practice. It is often the case that patriarchal culture privileges a stoic approach to creation (and being in general) and a pointed separation between artist and work. Within this value system, transparent emotionalism, especially coming from feminine sources, is considered frivolous. Allowing oneself to be vulnerable is in direct defiance with a culture that would rather us remain isolated, navigating the world through dispassionate power moves, in lieu of a more considerate relation. The project of “go on take everything” envisages community as the space we create when we allow ourselves to care for and with others. In tandem, emotion, whether it inhabits typified avenues of relation or not, creates a community of feeling. Whatever social parameters exist, this field of being is indestructible. We need only open ourselves to its infinitudes.

Back to Articles