alone in the open

Just before the crickets quiet themselves the sun appears at the horizon and the birds begin to sing… a fleeting duet. Shadowy places are disappearing but heat is not yet rising with the sun. In this hovering between night and day there is a moment that stitches together darkness and light, sleeping and waking, dreaming and doing.

John is about to leave, once again, for our other home and I will stay. I already feel myself entering into a shifting place where alone and together are both present. I know I will soon question why I have stayed, but I wondered if I can briefly hold the place in-between when both realities are sharply clear and neither fully grasped.

Since October of 1971, I have shared my bed. John and I met on a weeklong campout in the Blue Mountains, crawling into the same sleeping bag that first night. I remember the feel of his pajamas against my legs, the cotton fiber worn soft. My slim dorm room mattress was our next bed and then a flabby waterbed in the living room of someone else’s apartment where we slept under the same sleeping bag we’d shared in the mountains. Later, still 18 years old, we slept in a yellow steel framed double bed in an old farmhouse full of college students who were learning more by making a life away from their parents than from the classes they were taking. We left that communal life for another bed on the ground in a canvas tipi. We’d sold all of our records and my dulcimer to raise the one hundred dollar price of a mail order kit. We stitched the pieces together and everyone thought we were brave. A lot of time was spent lying on that bed on the ground in the tipi, staying low and out of the perpetual smoke and gradually learning the reason North West Costal Tribes did not prefer this habitat of the plains. Was this our first brush with desire for a dryer more vast landscape, or just the foolishness of young love?

The place we’ve bedded down has changed and changed and changed, sometimes lasting a night, other times years. The most radical move may be the most recent; not a move exactly but a pattern of repeated migration from Montana prairie to the Washington coast and back again made radical by virtue of the journey not always being made together. There is nothing of our shared bed I wish to escape, but the desire for occasional solitude seems to necessitate it.

After taking John to the airport, the 2-hour return drive through the vastness of the eastern edge of the Rockies has nothing to recommend it. I usually love this drive but today I am asking myself why I choose this barrenness. Why do I choose to be alone? The questions I knew would come are raw and real.

On this first day, in the schoolhouse, in my “room of one’s own” even the sun refuses to show itself. I had thought of calling John, but there is a catch in my throat that I don’t want to release, so I sit still in the kitchen, held by the familiar green Naugahyde of the dinette chair rescued from my childhood. Later, walking past our bed I cannot imagine getting into it. I am the only one generating sounds and I have completely forgotten how to be alone. The minutes tick off and the night looms large.

Ultimately, I find myself occupying a slender strip on one side of our mattress, the rest neat and empty. His absence is tangible. Lying very quietly, I remind myself of my desire for solitude, of my belief that to be alone with yourself is to know yourself. And I remember Solnit’s reference to the story of Frankenstein suggesting that to not know yourself is dangerous.

My childhood closet in the house my father built was small and cedar lined. It smelled dense like the evergreen state itself. At the bottom of the closet with tiny dresses and sweaters made by my mother hanging overhead, was a square toy box painted deep red. I remember little of what was in that box, but I do remember emptying it of its contents and crawling inside. I may have even closed the closet door. It was not a hiding place. It was merely my own place.

It has taken decades to really see central Montana, though I have been visiting all of my life. I never disliked it, there was the novelty of the ranch and the cousins and my Aunt Carol who was like my mother but smelled of cottonwoods, slightly sour milk, and wood smoke. My father loved to hunt with these cousins and my mother loved to be with her sister. I sometimes went to school with my Aunt Carol where she was a teacher. While I fondly remembered each trip by its events I never thought of the landscape. It existed in the barrenness of my mother’s Montana color photographs of “scenery” taken in the 1950’s and 60’s. Had the colors faded? Were they just the product of the technology of the era? Or had I not yet been able to understand the palette of Montana? Back in our Washington home, I always quickly turned the pages of our family photo album past those muted rectangles looking for pictures of people. I couldn’t find anything in the rectangles of muted color and openness. I might have called it bleak, if the word had been in my childish vocabulary. But now, 50 some years later, I have chosen this landscape, one that I call barren only in my impatience. Any eager looking for something more is similar to the impulse to fill quiet spaces in conversation, not recognizing them for what they are.

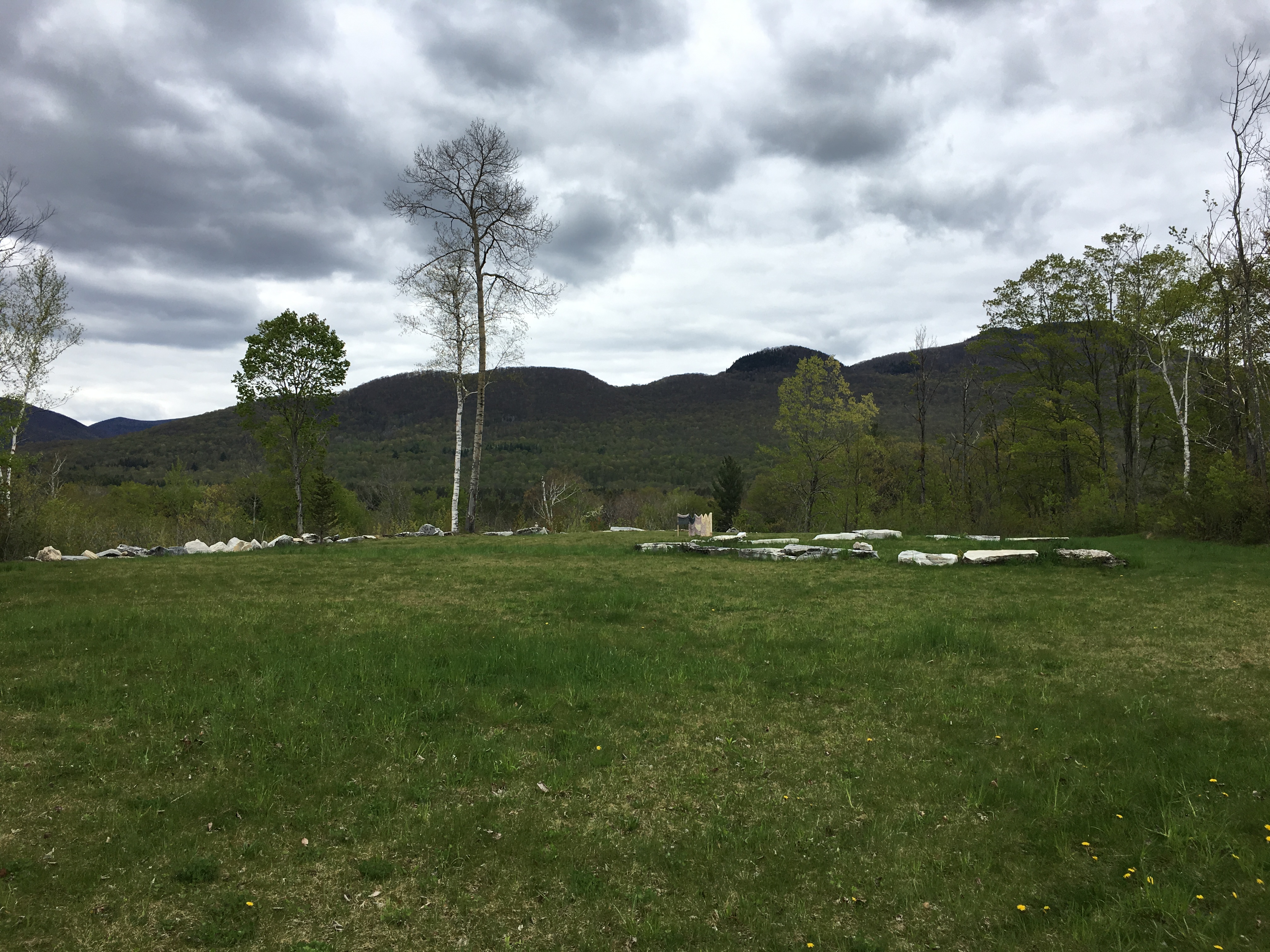

Solnit recounts falling in love with a particular place and throwing herself into its vastness whenever she could. I’ve begun to feel myself falling into the open spaces of this place that lies between the curved parentheses of one mountain range and another on either side of the prairie. It remains critical to me to see those curves, to be held by them so as not to fall forever. I’ve heard of places like Kansas and Iowa where nothing holds the openness. A fall into the depth of such a place might be never ending. But I only imagine it, never having been there, always clinging to the sight of not so distant foothills that comfortably hold the space between.

The schoolhouse windows open onto the landscape; six portals in each room. Each square equals a dash of horizon, each dash part of the view out. It is a place of looking where eventually I can become calm enough to look at the same scene over and over each day.

I am sleeping diagonally in our bed now, a luxury of being on my own that doesn’t quite make up for the missing, but it is possible to hold both at once. This morning I woke with sun streaming into the windows and remembering my dreams, couldn’t imagine being anywhere else. I’d dreamt of stitching embroidery on gauze as flimsy as the clouds in the sky and of capturing the light on the floor and holding it… this is a beginning. Perhaps the missing can fuel rather than consume.