Essay by Ben Gannon | Photographs by Sierra Stinson

wisdom of the underworld

Arriving at Joey Veltkamp’s February 2017 Vignettes exhibit, it was clear from the street looking into Rachel and John’s house that this show was dealing with the supernatural. Hanging in the front room window were sheer fabric panels with appliqué patches of heavily shadowed and made-up eyes announced the other-worldliness. Spirits are present and in many forms. A haunted space, like all indoor spaces at the end of winter, so charged with telekinetic and telepathic energy of its occupant(s). A haunted house, but in January (unlike October) we are familiar with ghosts, and in the January of this year the powers of naked death ascended to the leadership of the world.

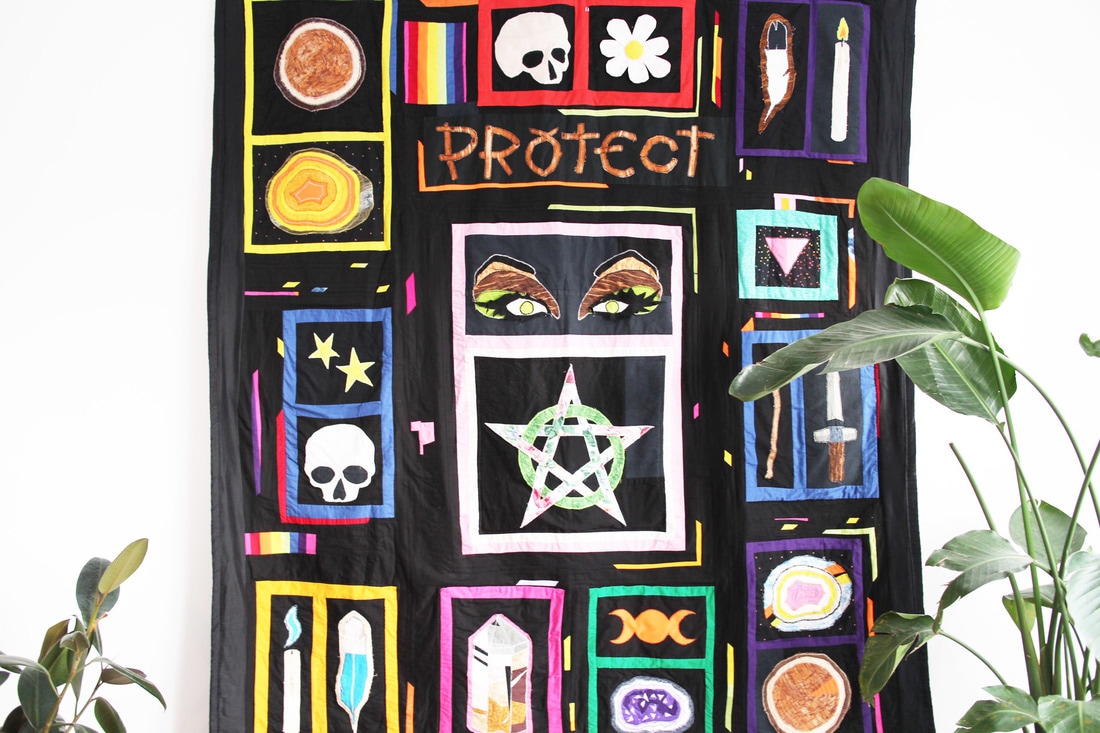

Once inside and in the first room of the show there hangs, along with the sheer panels, a large black quilt. It is composed of spells and talismans, each smaller square housing a symbol of power and protection, an anchor point from which to journey into darkness. Skulls, crystals, pentagrams, the word “protect” in appliquéd ‘wood’ letters—homage to Gretchen Frances Bennett’s found stick word art.

Sharing the space with the eyes and the spell quilt were a pair of pillows placed on chairs, each with a broken heart emoji, invoking the kind and tragic power of Laura Palmer, another symbol of strength and resistance. It becomes clear that wherever the journey of these artworks is headed, grounding in power is necessary and some danger is present or lies ahead.

In the next room more sheer panels hang in the windows and more eyes look out from the gauzy material. Along with the eyed panels there was a table full of small ceramic ghosts painted up like the cosmos and sitting on small, round mirror disks, the infinity of their motif reflecting into infinity. There is little distinction in Joey’s work between outer space and the underworld – vacuum and death both infinite and un-survivable phenomenon.

Binding this second room with the first was a pair of flags and a new motif for Joey’s work – a black cat appears on the flags, almost identical to each other—the latter done by memory, on opposite faces of a wall, each with the phrase Déjà Vu appearing on it, the lettering the same but the colors slightly different and the cat figure in slightly different positions. This diptych is a direct reference to the movie The Matrix, where the repeated sighting of the same black cat as an experience of deja vu is revealed to be an indicator that there has been a significant change made to the fabric of the world of the matrix. Not only a personification of the phenomena of change, the cat is our familiar and our guide while traveling through the dimensions.

Also hanging with the eyes, the cats, and the cosmic ghosts is one of three quilts of its kind in the show. Multi-tonal, textured blacks patched together, the chorus of darkness interrupted with flashes of heat and light in the form of randomly sized triangles, trapezoids, parallelograms and rhombuses of color. Two more of these burning landscapes hang on the walls leading up the stairs to the final room of the show. Akin to the blending of the underworld with outer space depicted with the ceramic ghosts, the landscapes depicted in these three quilts is both of the fire of space and the fires of hell. Accompanied by the indifferent harbinger in the form of the black cat, we are walking with Joey through the cosmic underworld.

The final space of the show, past the watching eyes and glittering ghosts and burning voids, is the bedroom upstairs. The sole artwork in the room is a quilt lying on the bed. The cats again appear; this time en masse and in distinctly different poses, on the quilt upstairs, the resident housecat Brigitte having found a comfortable spot for itself on the bed as well.

But what are the lessons from hell and the vacuum, of walking through this heartbreak simulation? Joey’s work participates strongly in the realm of the pop culture oracular, pulling in and manipulating the signs of culture of the moment, playing in their subtleties and shifting them around before casting them back in to the infinite sign constellation in the form of fabric objects with meanings made from Joey’s particular alchemy of working with sadness and elementally reconfiguring it into joy.

But all oracles have limits to their vision into the ocean of possibilities. And it is the brave or unprotected oracles that, in the midst of confusion, go deeper, towards the leveling wisdom of infinity and death, and the freedom brought forth from acknowledging that wisdom. In the face of the cruel madness and absurdity so evident in our world at this time, the reminder of our death is a reminder of our life. In the face of the infinite void of space, we are able to refocus on ourselves with a grounded perspective.

But it is not all grim contemplations of death and freedom and endless emptiness, and the cats in their various poses on the final quilt in the show remind us of that. With each change or glitch in the fabric of our worlds, with each appearance of the cat as a harbinger of change, there nonetheless remains the infinity of other worlds with other changes and glitches occurring all at once. If the wisdom to be gained from passing through hell and space is the infinite of the void, the wisdom to be gained from the multiplicity of black cats is the rich infinity of being, existence and possibility.

Andrew Lamb Schultz’s Salvaged Fantasies

Essay by Steven Dolan | Photographs by Sierra Stinson

Recently I found myself arguing the value of Andrew Lamb Schultz’s work with a friend. Their conceit: it’s cute (as if that is insufficient). BUT! I protested, doesn’t cuteness have transformative potential? Isn’t it possible to create work that is immediately satisfying for its surface level appeals to the flexing of our cheeks, that also does more should you so elect to live in a world where cuteness can be radical? “Cute” is certainly overused in my own vocabulary and can be invoked to infantilize and reduce people and actions to a pleasant passivity. Sensitivity to this is important, as is the context of its invocation.

Also important is recognizing that language is mutable, and that the terms of terms can be mutated and changed, queered beyond historically violent structures of power. Tracing the etymology of “cute,” one arrives first at acute, then variously: a needle, to sharpen, to arouse. “Cute” needn’t be regarded as exclusively slight. It’s cute when you hold your drunk friend’s hair back, it’s cute when strangers ask your pronouns, it’s cute when a bank is called to task for their support of unethical development, it’s cute when a neo-Nazi gets punched in the face and a proliferation of the video is accompanied by an exhaustive slew of soundtracks. Cuuute. Feel it.

Trust functions only if experienced mutually. Intention alone gets us very close to nowhere, but intentional listening is just as important as intentional speaking. Lamb invites you take in their work, saying this is glorious, this is beautiful, love this and I will show you the way to a better world.

In considering their show Eutopos / Utopos, one should note the ways in which this is a personally idealized, or at least preferred, space to exist in. In a world built for a few, the culling of what is affirming and nourishing to construct or restructure space is necessary for the survival of those on the margins. It is the queer imagination that takes these facets of a “good place” perhaps a safer space, in the hopes of achieving the impossible but still vital utopic place. It is essential to queer political imagination that there is impossibility.

In a conversation about their show, I confessed to Lamb that I had a sort of fantastic vision of their working process. One version of this imagined reality sees them in a minimal space that is more a spatial field than physical room. Meditative and serene, it’s an illuminated void where the artist has a kind of psychic communion with their ideas and channels that energy into work that is manifested with ease. I can only conclude that this sense comes from their images (and my own desires for work/art/love to be summoned on command), which has clung to me like a spectral dream.

This, of course, is not how Lamb works. They’ve described their practice to be compulsive, wherein doodling happens in the in-betweens: on work breaks, between day jobs, on the bus. Art work happens post-day job.

There is little time off. Much of the work created for the show was produced in an unorthodox studio space in a Capitol Hill basement, which could certainly be romanticized, but one resists. This show, like much of their work, nurtures with the proposal of a less chaotic world, a less demanding world; fantastic therapy that embraces the viewer with a sense of calm and affirmation: things could be different.

“A lot of the images and a lot of the drawings I make, are me depicting the daily life I want to be living that I’m not, and a lot of that is leisure,” Lamb told me. These dreamscapes are for their friends, their community, proletariats if you will. “It’s like meditations on Marxist ideology in a way.”

Lamb’s work opens a prismatic set of fantasies, some which feel within reach, and others that are seemingly impossible in nature. Such is the dichotomy of the show’s title.

“A lot of the images and a lot of the drawings I make,

are me depicting the daily life I want to be

living that I’m not, and a lot of that is leisure”

Lamb is an artist who creates a world, one with a particular vernacular that allows the viewer to consume the work as far as they choose to see in it. One can accept the sweet loveliness of the work on aesthetics alone, though its keener readings open greater dialogues around humanity and its relation to the world.

In Reclamation I (Mossy Ruins), Reclamation II (Mossy Nude), and Mossy Figure, the artist integrates plant life with human signifiers, whether they be built structures or figures themselves. Drawing on the architecture and sculpture of classical Greco-Roman antiquity, the supposed building blocks of Western civilization, they imagine the possibility of a human footprint becoming more enmeshed in nature. It is through natural interventions that signifiers of the violence of civilization are reclaimed. So-called development has been pacified and recycled for its aesthetic value.

Moss has been transformed into a delicately rendered system of multiples rather than a solitary blanketing substance, looking no less consuming. A departure in medium for the artist, Mossy Figure is a silk-screened soft sculpture. A pink figure embellished with bottle green faux fur and found artificial flowers sits atop a pedestal painted on all sides as if a column. Lamb’s hand is still ever-present as the planes of two dimensions cross over to three, a kind of trompe loeil play. Such an illusion is useful in understanding the way queer identities and genders are presented and perceived: what one sees may have a dissonant reality not visible to the obstinate eye.

A four-panel wooden screen painted over with mantises and orchids constitutes another departure for the artist. Here we have an aestheticized object, one rendered in soft pastels and tender crudity, that would most typically

exist in a feminine boudoir. This piece, however, carries greater venom than its flamboyant anachronism suggests. The title, Judith Screen (Orchids and Mantises), recalls the Biblical story of Judith who seduced and beheaded a drunken Holofernes, a general of Nebuchadnezzar leading the invasion of her home Bethulia. This context is paired with the erotic orchid and a predatory insect culturally associated with the femme fatale. Orchid mantises have adapted to resemble their namesake flower, a camouflage that obscures them from the view of both predators and prey. Further, many females of various mantis species practice sexual cannibalism, which sees them feeding on their mate; head once fertilization is secured. But reading this piece under the uncritically nostalgic, historically violent credo of “The Future Is Female” would be a mistake. Binary logic should be abandoned here, as everywhere. Along with Lamb’s figures, potential perceived gender markers should be approached with suspicion. Exclusionary feminist art historical derisions of present phalluses need not apply. What emerges from the work is a contemporary femme allegory: being seen can be dangerous and counter to survival, but there is power in reappropriating our surroundings, strength hiding in plain sight.

While the symbols employed are associatively female, they stand as narrative pillars of self-actualization. Integrated in a non-binary narrative, these markers are used expansively, pieces of a historical mosaic, recycled fragments of a queer architecture, revealing a flourishing potential in the spectrum of relationality. Among the pictorial and metaphorical ruins of civilizations past, what remains is a call to expanding our vision for the future. Part of this work is taking note of and cultivating the good, salvaging what we can from our failures. This also means recognizing that one’s version of “good” may not be universal. We will continue to fail every day all the time forever, tragically so, but we must keep grasping toward the impossible.

Through A Window, Down A Portal

Essay by Kim Selling | Photographs by Lynda Sherman and Sierra Stinson

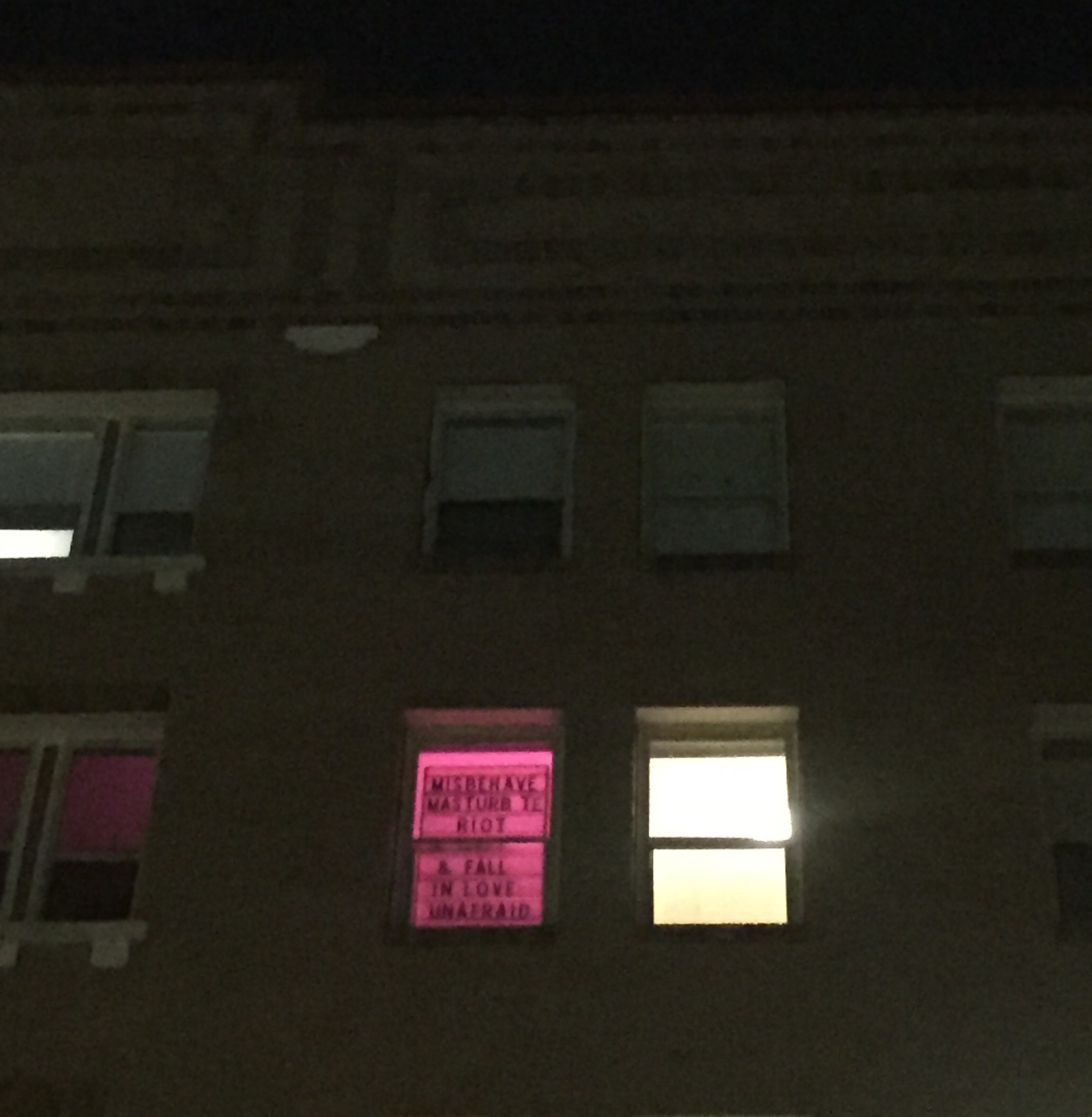

Beginning this year was a piece of simple distinction, plain text projected over a heavily trafficked corner of a rapidly changing neighborhood. Small collective phrases like singular light bulbs, one alit each night for the birth of 2017. To create something from nothing at the turn of a linear time cycle means that all context from previous cycles have been mined to give this current one a deeper meaning before it has had a chance to play itself out. Lynda Sherman’s The Usual Window uses the peculiarly traumatic experiences of her childhood to create a scene of power dynamics, represented by her chosen avatar, text, in a way that is immediately translatable and digestible for modern viewers. You see the phrase, it is now yours, and will hopefully be used in your own illustrations of self.

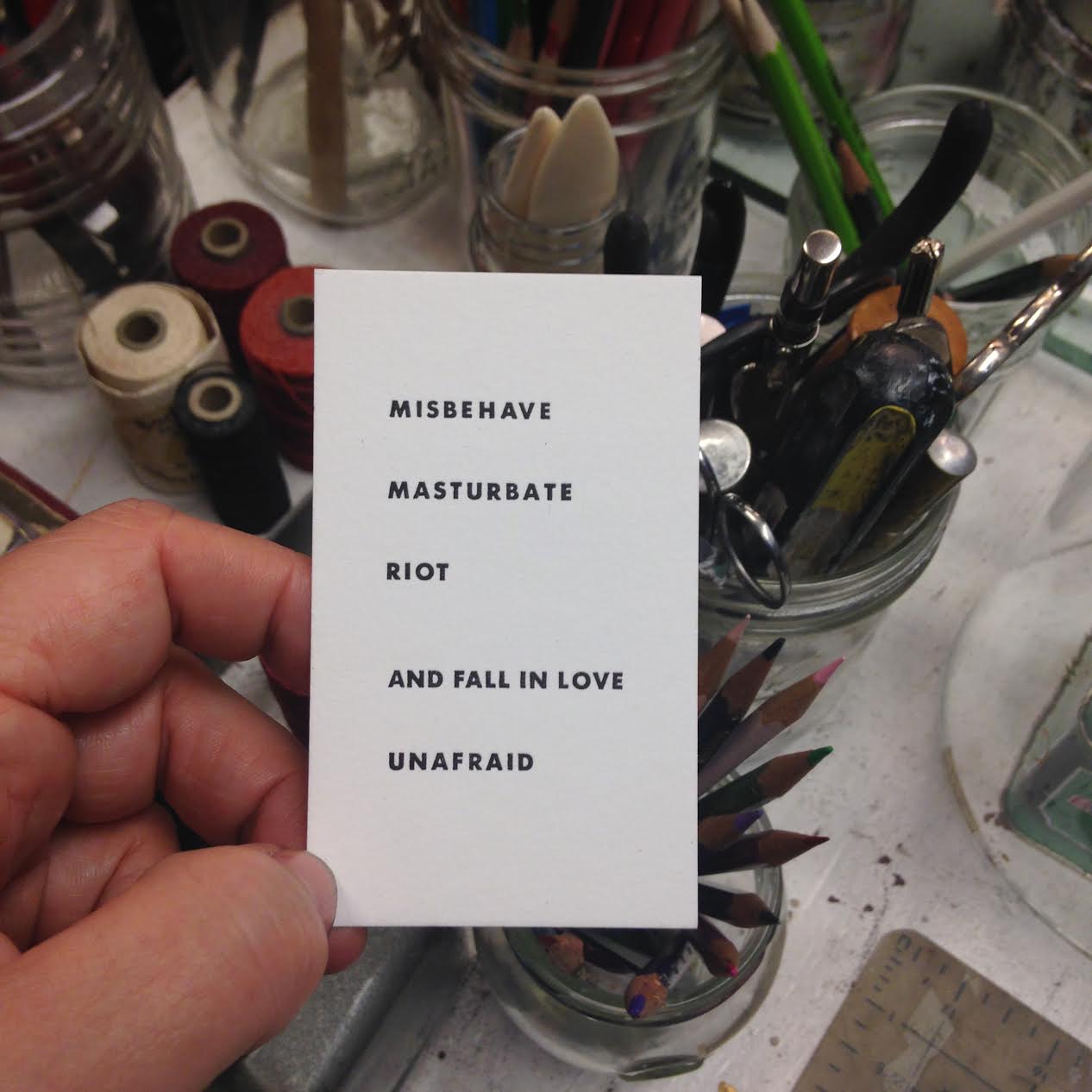

These phrases can be read in any way the viewer chooses, but, in any case, are as follows:

MISBEHAVE MASTURBATE RIOT // AND FALL IN LOVE UNAFRAID

KEEP HEAD OUT OF OVEN THUMB OUTSIDE FIST // HEART OUT OF POCKET STITCHED BACK UPON SLEEVE

REQUIRE DESIRE

INCITE DELIGHT

RAGE FORBIDDEN GLEE // AGITATE FEROCIOUS PLEASURE

CRACK SPARKLE PEEL // UNRAVEL ALTER FOMENT

glimmer gleam growl // wage and devour

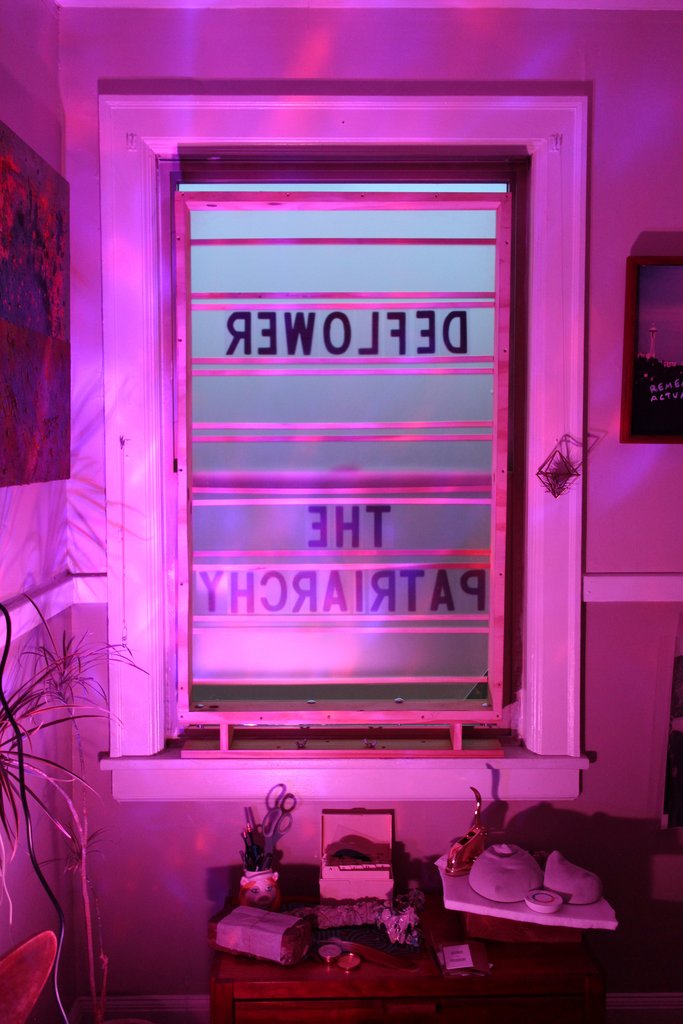

And the 8th day “bonus track,” DEFLOWER THE PATRIARCHY

As a child in Bremerton, Sherman grew up in a classic prairie rambler with her family. Her bedroom window, the usual window of this show, was pink, framed by pink checked curtains and a white vinyl shade, and distinct not only in its Pleasantville-like appearance, but in its openness to the outside world. One of her neighbors, a non-descript bus driver, would take it upon himself to look through this window often, peeping at Lynda in this room and others throughout her house. She never told her parents, instead internalizing these trespasses as a child, and informing her later experiences regarding safety and consent with these early incidents of voyeurism.

Starting as a literal experience and slowly morphing into an extended metaphor, the “usual window” continues to serve as a direct illustration of Sherman’s treatment of her own body and mind as dual and separate entities. When pressed on her attitude towards herself, Sherman responded: “A lot of artists think about ‘the voyeur’ and that’s something that makes me very uncomfortable, to be seen physically. And I’m not sure if it’s because of that, but I exist mostly in my head and not my body because I don’t want to be just seen as that, and that’s the thing I can control more, is my mind. And that’s mine, that can’t be taken from me by anyone trying to insert themselves into my life or into my mind.”

Infiltration by outside actors is impossible when you’ve proved yourself capable of both severing and filling the spaces between your body and your mind. Sherman mentioned her ability to dissociate often without even realizing, operating both within and outside of herself as she goes along. She remarked on the confluence between the two states within the act of printing: “Even though you’re tuned in [to the printing process], you’re still hyper aware, and I guess that’s the only way I’m aware of my body — is when I don’t wanna have it chopped in the machine. That’s how I know where my hands are.”

This ability to give and receive your own sentience makes for compelling dictations on action. The statements put forth by The Usual Window play with directness, with providing a to-do list of constant vigilance in how you care for yourself. And Sherman separating her selves allows for her to direct her body and her mind in different but dovetailing causes. In discussing action, Sherman said: “Most of the things I print are like daily meditations, and it does start with me. It is a mental health plan.” Using these disembodied statements work chiefly as a to-do list for both the artist and the audience, clearly outlined for each desired action, to be interpreted differently by each viewer depending on their own mental and physical duplicity. “I think it’s a mental health plan, because otherwise the words just spin in my head. It’s like an energy that you can then release.”

That energy can’t exist in a vacuum; it exists within the realm of Sherman’s larger understanding of her own capacity to effect change. This faceless, body-less narrator can usher art consumers into a new understanding of themselves by virtue of its mutable and truncated message format. She claimed: “A lot of people don’t wanna have to participate in their own understanding but those that do, it could be another portal to use something differently or use something more in depth. Even though there’s so few words I think that each one of those words is its own portal that you can go into. I know that there’s some people in my own life who have such a resistance to that, they don’t even wanna go in those portals.”

Sherman’s deep-seated connection to these portals, each word she used in the show serving as their own vehicle, is more than just message-related. In response to a question about action in creative communities, she mentioned that “I see much more participation and less consumption now, sometimes literally. And I think that’s an important move, to take your own narrative back. And to see people taking their own narrative back through sadness and anger and action, also seeing people realize that it’s not an energy that dissipates into nothing.”

Choosing to take back your own narrative in these trying times (read: really all time, not just this one) involves plunging yourself into the portals of Sherman’s words, which in itself is an almost divine action of shooting for your highest potential as human. So utilizing Sherman’s statements for pointed improvement and increased agency brings us to this central question: can you truly divorce your self? Can mind and body exist separately outside each other? And is this possible without trauma being the vehicle for separation?

Trauma forces us into a compacted uniqueness. We must compartmentalize to remain above what pains us: what to keep and what to throw away, what defines us and what creates a version of us we’d rather not know. In an interpretation of a Usual Window phrase: wage war on your character, and devour what is lacking. Is such divisibility of spirit possible without the definitions of trauma? Without the trappings of guilt or overcorrection, could you ever simply be just a girl at the window?

Of course, the answer is a singular moment only to fit a framework; what matters is the process of separation, realizing one’s agency in solitude, and deciding upon a course to follow, now free (or lonely) of one’s self. Once the body is no longer there, the mind can communicate without boundaries or limitations. The weightlessness of a mind freed from its physical constraints, now able to act or project in any desired way, say, to masturbate-riot as loudly and frequently as possible. Since a freed mind can’t corporeally do that on its own, it can, at the very least, compel everyone else to in its place. So it is, in its way, a figure of universal nature, joining together all of its audience, each of whom have decided to look through the window.

Not to drag this into a Hot Topic echo chamber of neopagan trutherism from which we can never recoil, but this current time of year (typically March 20-April 1) was previously celebrated as the beginning of the new year — a separation of seasons at the vernal equinox allows the world to be born anew for the next cycle of time. This phase of year that we’re in lends itself to separation of the selves — a lifting of the metaphysical veil between soul and body — and re-commitment to physical and emotional goals.

Lynda’s piece was presented at the beginning of the Roman Calendar new year, the beginning of January, so this connection is not totally out of nowhere. A traditionally pagan tradition of this time of year was to write your intentions upon an egg, visually setting your hopes for this new year onto a symbol of impending creation and thusly, subsequent delivery. You bury the egg, and then plant seeds of your choice into the plot of dirt where the egg is buried. The seeds then suck the nutrients out of the egg as they grow into the plant they are meant to be, thereby expanding your hopeful intentions and becoming a tangible representation of how you, yourself, hope to grow.

Each day of The Usual Window, Lynda wrote her intentions on these windows, soon to become actions of hers and of ours. We must promise to and go forward with misbehaving, masturbating, and rioting, inciting delight, requiring desire, and actively deflowering the patriarchy. This is our to-do list now, the explicit actions that will spell out our future.