Minh Nguyen’s essay response to Leena Joshi’s exhibition “home island bye bye”

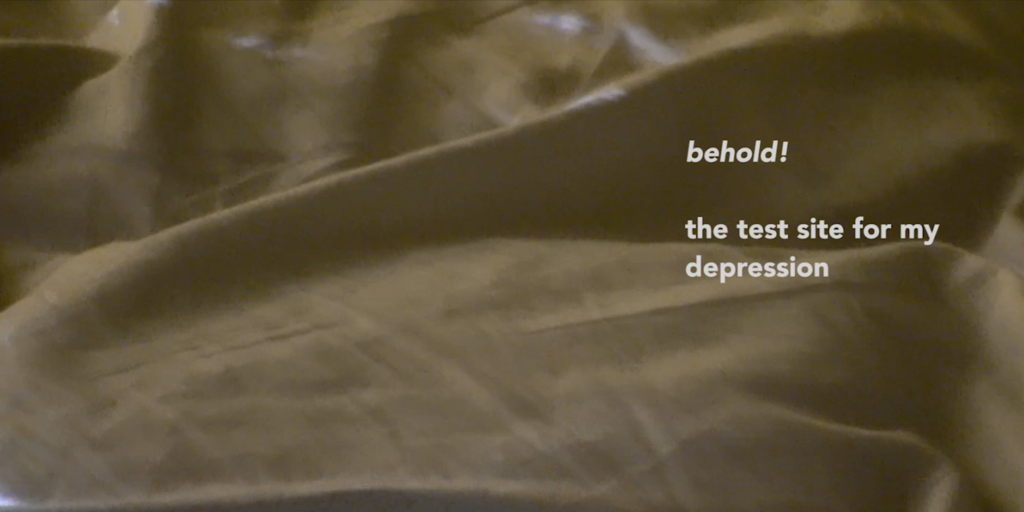

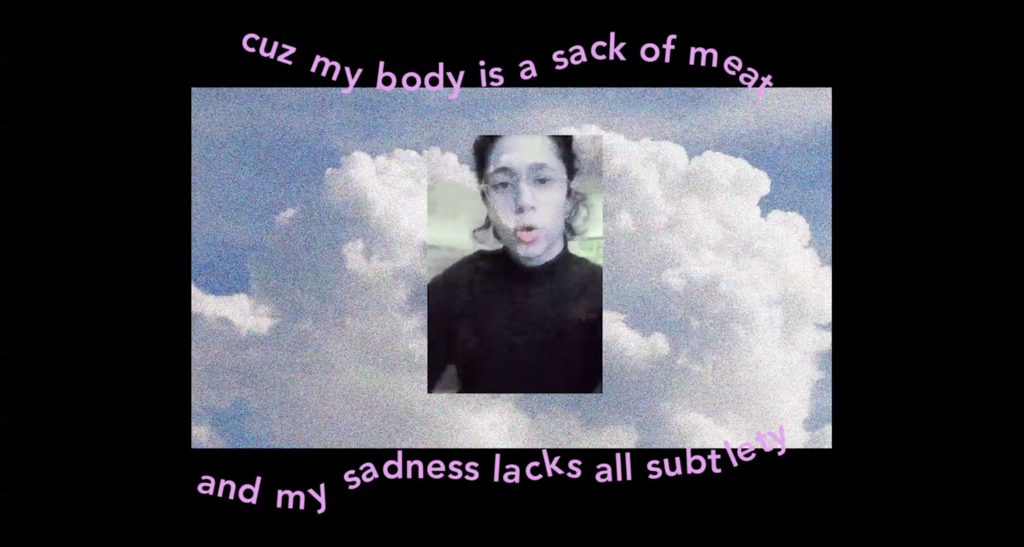

stills from “Profit TV” single channel video. 2016

Inedible Sadness

In the Middle Ages, European theologians asserted that melancholics, characterized by long-term despondency without cause, were gifted clairvoyance through vivid dreams. Sadness was sign of a wise spirit, a supple spirit, a spirit described by the Italian monk Tommaso Campanella as “more subtle and more gifted than the spirit that is too thick.” The thick-spirited sought in the melancholics to analyze their dreams for auguries. When my depression worsened this year, my horrible sleep yielded paltry dreams, and I became more depressed, paranoid that I wasn’t smart or deep.

2016 was a year of sleeplessness for both me and Leena, and 2016 was definitely not a year of foresight. Our sleeplessness is a symptom of our depressions, separate and simultaneous, that had been long-simmering, all to boil over after the election. When they boiled, hot foam frothed everywhere. We spoke about it openly. We sent each other photos of ourselves in bed with 5pm light on our faces, depression foam covering everything. The foam was even on Instagram. At one of the worst periods, the subject of our insomnia Instagram DMs got really specific: misguided instructional cooking videos. Videos of overly-complicated and inedible recipes. We shared them and tore them apart dramatically, distracting ourselves from the reality that we had to get up in a few hours.

“WHOSE LIVES ARE SO TOGETHER that they can arrange a serving of rice in a lattice of cheeses” – 3:45 AM

“It’s worse, it’s a lattice of egg!!!” – 3:45 AM

“I can’t sleep as usual, been trying for hours, lol” – 4:15 AM

There’s a joke that goes something like, how do you express your depression on the internet? Start with ‘I’m so depressed’, then add ‘lol’

“I’m so depressed lol.” The marriage between comedy and depression is eternal.

One of our favorite places is Bush Garden, a karaoke bar that paradoxically retains the feeling of being a secret despite the fact that everyone in town knows about it. We would suck our diluted gin-and-tonics through two small straws and brush our hands across the laminated pages of the karaoke book. Which tragic songstress would we be tonight? At karaoke, your anguish was melodic and it had an audience. Around Christmas, the trees come out in rampantly plastic blue and white, along with the colored lights that make the room look wet and smeared, an effect that backdrops movie characters in scenes of attractive tragedy.

I won’t go on about Bush Garden because there’s a whole essay in me about that place. I think there’s a whole essay about Bush Garden in most people I know. There have been long-time warnings the place will shutter its inviting double-doors for good, and many have written about its charms and powers. They call Bush Garden one of the last hold-outs in Seattle. There are so few ways to truly hold out.

“Let’s go sing one song,” Leena says after dinner. “One song” is the most blatant lie in our friendship. Folded into the plush booth seats among strewn bags and jackets as if in someone’s apartment, we typically outstayed everyone. On one occasion of this pattern, we had been talking about people moving away before we got to Bush. I pulled out my phone to read the Facebook status of my close friend Marcel, who finally left Seattle after years of dissatisfaction. I read his words out loud, pacing each sentence with gravity and emphasis. “I had to let some things die in order to give life to other shit. I had to quit.” Halfway through I started crying and Leena started crying. We cried at each other as someone’s pop performance washed over us. “I want to leave.” “We’re going to leave.”

Where was my origination? people always ask. you must tell others where your allegiances lie, to whom you are an ally, and that implies the fact that you know yourself. at some time when in between on a plane over the atlantic I got stuck. my skin stretched over the whole earth, thin with distrust.

– Intro text from ‘Profit TV’

We constantly talk about leaving, and moving away from Seattle is the literal idea. Sometimes I wonder if I’m mistaking the desire to escape what ails me with the desire to put my body in a fast-moving machine and let it jet me away. The older I get, the more aware I am that our so-called site-specific depression, this blame we place on geography, is too easy. It may meet up with us eventually, despite our grandiose plans to outrun it. And even if we could, even temporarily, where did we want to go? Somewhere we can sleep better? Somewhere we can read the news without feeling scrambled with nausea, fear and hopelessness? Somewhere we can be less suspicious of people’s intentions? Somewhere we could feel at home? I’ve mentally ran a magnifying glass across the nation to find this place but came up uncertain. We could go to the lands of our families, but our years in America are rubbed on us. Vietnam and India, those aren’t our homes either.

The word deracination comes from Middle French to refer to the literal uprooting and eradication of plants. It also means to remove something or someone from their “native roots.” I read about this word in an essay Keguro Macharia wrote called On Quitting, about his decision to leave the University. He expressed the feeling of deracination as “to be loosed, to be unmoored”, like when a ship is slipped away from its anchor. I’m not sure if I feel unmoored as much as I wonder if there was ever an anchor for my vessel.

Before Lauren Berlant wrote the widely-cherished book Cruel Optimism, she was part of an art collective called Feel Tank Chicago, which operated with the goal of expressing “public feeling” or “political emotion.” Unlike obscurantist art language, FTC was informal and tongue-in-cheek. For their International Day of the Politically Depressed parade, participants were invited to show up in their bathrobes to indicate their fatigue, or in t-shirts that read “Depressed? It Might Be Political!” They wanted to depathologize depression. Unlike the monks in the Middle Ages believed, depression wasn’t an innate gift from a higher power but the manifestation of the body’s response to external conditions. Depression isn’t your biochemical imbalance, your gift or curse.

Ann Cvetkovich, who authored Depression: A Public Feeling, writes that depression can be “traced to histories of colonialism, genocide, slavery, legal exclusion, and everyday segregation and isolation that haunt all of our lives.”

I never needed affect theorists to tell me that the paralyzing sense of hopelessness is political. As a person of color, that fact seemed self-evident. And yet, what Feel Tank Chicago never got to addressing was the tension between the performance of affect as a gesture of political protest and the internet’s techno-utopian project of the transcension of race through representational multiculturalism, resulting in what we have today as what artist manuel arturo abreu calls the commodification of identity. Political involvement in the art world can amount to a cherry-picking of marginalized identities (one queer artist expressing their struggles, one refugee artist, and so on), conflating the relationship between pictorial and political representation. Galleries and museums circulate affective art by the marginalized to gesture at political investment and solidarity with those communities at large. It is the foreign entrée in the aesthetic buffet. Behold! My depression.

A refusal to play into the appetite of the market, to speak to one’s marginalization and provide catharsis for those who mix up sympathy and political action, is often at the artist’s disadvantage. Capitalizing on the zeitgeist will help you get paid, and who doesn’t want to get paid? In times of fiery political unrest fanned by the online circulation of images through traditional and peer-to-peer media, there is even less investment in marginalized voices when they aren’t pedagogic by white standards.

You create straight-forwardly and voice your pain in a consumable way, and the industry traditionalists will sneer and call you obvious. You abandon making any appeal to your humanity, and risk losing a wide audience and thereby monetary opportunities. Art critic Merray Gerges writes, “BIPOC [Black Indigenous People of Color] artists are given two simplistic and contradictory options: 1. Make identity politics “your thing” as a native informant who epitomizes this category; languish in cultural centres funded by fickle equity grants; risk alienating white audiences; or, 2. Assimilate the language of white formalism; whitewash yourself to be palatable enough not to make white people uncomfortable; risk alienating your predecessors and others like you.

You’re damned if you do and you’re damned if you don’t.”

・。・゜・。・。・゜・。・゜。・。・゜・。・。・。・゜・。・。・゜・。

I can only end by expressing what Leena’s work means to me. It’s about the fatigue of being a female-identified person of color in the specific terrain of art, but that’s not the nucleus of the work as much as it is the sheer but all-encompassing membrane. It’s about feeling that the place you’re in is not your home while suspecting that your home may not have geographic coordinates. It’s about how, despite the vexed history of sadness, sometimes the sadness isn’t articulate or interesting: you pace the streets and go to karaoke and lay in bed hours after waking, letting the foam bubble over everything.

<< heartbreak simulation >>

new work by Joey Veltkamp

January 26, 2017

This is a show about memory: how such an easily corrupted phenomena shapes our truth and defines our reality. The way we remember the things that happen directly determines how we perceive reality. And since we cannot agree on what constitutes our shared reality because we all remember differently, how is existence and interaction with each other anything more than a practice in grief; a cycle of coming together only to come apart when the temporary truce of a shared reality breaks down? Are we at the dawn of the creation of our own reality as futurist Elon Musk suggests? Or are we at the end of times, as death cults have believed for centuries? In either case, this unbridgeable distance between truths, reality and shared memory traps us all in the prolonged division of a heartbreak simulation.

Detail from “ARE we real?” Simulation (Elon Musk says our reality is a simulation and I find that oddly comforting) Fabric and THREAD, 2017

home island bye bye

Leena Joshi

January 11, 2017

My fondness for aging (the deeper, softer, squelches of my own hand reaching inside my thoughts to withdraw the good stuff) is sharpened by how growing up means now understanding sadness. It’s time for an art show; my heart is broken and I’m at my most depressed. By the time I’ve rinsed the sleep off of me and pulled my aching body out of bed it’s night already. I’m still fixated on an egg, a palm leaf, my hands, an avocado seed. The pads of my fingertips stretch out looking for the texture that feels most like comfort, the fraying line of a silk piece. I had a hold on place once but I’m losing that grip. My parents were the first to show it: Rani right now you lack a place. Stop feeling sorry for yourself, you aren’t the first. The way ahead is long and far, yet I will search far and wide. Perhaps to move on forever is the trick.

As a child I thought my nation was my state of being. I drew on sidewalks welded with government wealth. the grass was always greenest. I visited the country where my parents came from and there I saw lack, and mass far beyond me. upon each return I examine the mass of my birth and the birth of the country I live in, watching it carve a very long dark tunnel. someone else is responsible for its state of ripeness. from there I felt my own somewhere complicate, but I was not yet fully stretched. where was my origination? people always ask. you must tell others where your allegiances lie, to whom you are an ally, and that implies the fact that you know yourself. at some time when in between on a plane over the atlantic I got stuck. my skin stretched over the whole earth, thin with distrust.

IMAGE: Test site for liminality, digital composite, 2016

www.leenajoshi.com

Dead People Never Stop Talking

Q&A with Michelle Peñaloza and Eric John Olson

Images by Eric John Olson unless otherwise noted

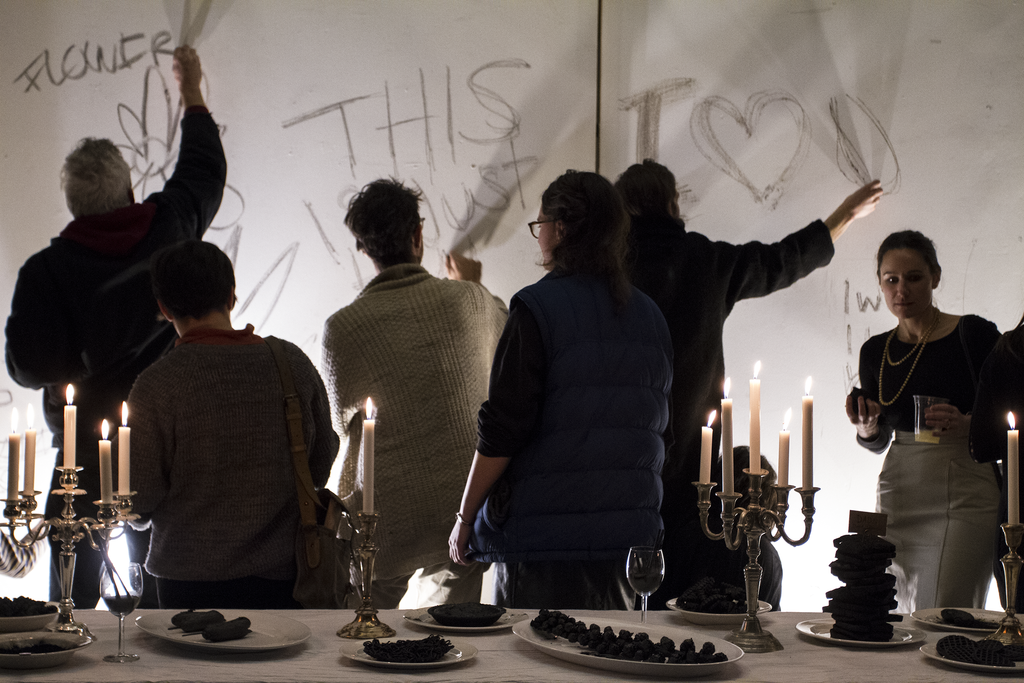

Image: James Harnois. We Are a Crowd of Others, exhibition by Gail Grinnell, Sam Wildman, and Eric John Olson

From September to December 2016, artists Gail Grinnell, Samuel Wildman, and Eric John Olson used their residency at MadArt Studio to weave together an expansive site-specific installation with a series of public programs that investigated the language and resonance of ordinary acts.

As beautifully written in her essay, “Author Redux: Neither Dead Nor Discourse”, Abigail Susik describes the site-specific installation:

“Artist Gail Grinnell constructs a massive site specific installation out of yards and yards of dyed spun polyester, the kind used for clothing patterns, in mimicry of the actions and movements embedded in her own mother’s sewing practice. After crafting achingly intricate cuttings in muted shades from the spun polyester, in meandering shapes that wander from swirls to skeletal patterns and back, Grinnell drapes the melancholy, lace-like lengths from hooks placed high on the industrial walls of MadArt. Grinnell’s son, the Portland-based artist Samuel Wildman, then gathers these fragile strips and incorporates them, on a continuing basis throughout the duration of the project and sometimes with his mother’s help, into a monumental funnel-shaped structure, reminiscent of a wasp nest, which swallows most of the gallery space. Next to this astounding entity, Wildman’s own sculptural assemblage, more intimately-scaled and made out of salvaged wood, liquid nails, and mason jars filled with concrete, ponderously accretes over time. Where Grinnell’s form emphasizes the forward-driving pulse of artistic production, the urge to expand, Wildman’s pinpoints on the other hand the halting precariousness of construction, the shyness of craft.”

Image: James Harnois, Installation by Gail Grinnell and Sam Wildman

The open forum of public programs gave the public, participants, conversants, poets, performers, and artists a space to interact and delve deeper into questions about how the past and future can haunt the present, making its way into our daily rituals. Projects included workshops for catastrophe preppers, public re-enactments of meals reminding people of their dead or dead-beat dads, screenings accompanied with science lectures, open rehearsals of a new dance by Tia Kramer and Tamin Totzke, and an exhibition of oral and visual histories of Seattle’s DIY music scene.

The following is a Q&A by poet Michelle Peñaloza with one of the artists, Eric John Olson, discussing the public dinner series.

Michelle Peñaloza : Where did the idea for the DEAD DAD DINING CLUB begin?

Eric John Olson : I wanted to create a way for people to talk about what absence means and how they hold it in their day-to-day lives. I was thinking about the ways in which we reenact people or do these small things that remind of us someone. They hold a memory of the loss and kind of act as a substitute for it. And then meals just seemed to fit in well. I was just thinking about recording people eating their dad’s favorite meal and talking to them about what it reminded them of, to have people all around a shared table and rendering that as a video installation.

When I was invited to contribute to the MadArt [“MA”] project, I talked to Sam and Gail about what I was already working on with this project and since there was a kitchen at MA, Sam was like, “You should host live meals!” I had hosted a potluck version at SOIL, but these felt a lot more meaningful for everyone involved, creating a re-enactment of each meal.

MP : What are some of the things that people have done for the different dead dad dinners? Have they been very different?

EJO : To start off the series, I did one myself because I felt that it was only fair.

For it I made a table that was tilted, one that went back and forth for each person sitting at it. You had to balance the plate on the table while you were eating. I wanted to try to represent the balancing act of talking about loss and grief; I didn’t want to make it easy for people to eat.

Then at one end of the table was a TV playing my dad’s favorite TV shows because he really liked to watch TV while he ate.

Abyssinia, Dad, Eric John Olson,

MP : What were some of your dad’s favorite TV shows?

EJO : … Star Trek and M*A*S*H. So, at my dinner, I played a M*A*S*H episode, a really sad one, where one of the doctors finally gets to leave the war but his helicopter gets shot down on his way home… and on the other end of the table, I placed my grandfather’s rocking chair, which my dad inherited and then I inherited. For [my dad’s] birthday, we would always make a big dinner and he’d always want Yorkshire Pudding and say “I don’t want to eat at the dinner table because it’s my birthday, since it’s my birthday I want to eat it while relaxing in my rocking chair and watching T.V.” So I wanted to recreate that.

MP : In terms of other people who have participated, can you talk about the process from you asking them to participate, to the development of their ideas, and then their execution of the dinner?

EJO : With each person it was quite different. I usually asked them if there was anything they’d like to reenact, how they would want to cook the meal, how did they want to set up the space for people to eat, and what kind of conversations we would want to lead during the dinner.

People did a massive variety of things—Norah’s was a BBQ; we barbecued in the back of MA. She really wanted people to talk about their favorite things about dads and about their dads because she felt that ever since she lost her dad, whenever people asked about him and she said that he was dead, that the conversation would just immediately cut short, instead of—

MP : Instead of her learning about people’s dads—

EJO : Exactly. So there was a whole discussion about that.

For Anne’s meal, everyone went around the table and toasted someone they lost; it was set up like a more formal, candlelit dinner. The recipe was based off of the last meal that she made for her dad when he was dying; she had heard that the “last thing to go” was the sense of smell and so she made this Pasta Provençal with lots of rosemary and garlic. She shared a whole story about that memory on the back of the menus, and that was a tearjerker. People were crying and sharing. It was a really beautiful night.

MP : Timothy’s was really interesting. I thought that was really cool; it was a different way to think about a meal.

EJO : Yeah, and… then, for Timothy, what reminds him of his dad is burnt toast. And that’s because, as he talked about it during the [event], his memories of his dad are really memories that his mom would tell him about his dad and burnt toast represented the chaos in his family, of growing up without a dad, because he lost his dad so young, and kind of the instability that that created in his family. Whenever she would burn toast or some dish his mom would say “but, your dad loved burnt toast,” and he recollected the fact that she always tried to talk him into being like his dad… and so for him, it’s almost more about the stories that we hold and what they tell about the absence.

So he decided to take an entire meal and burnt it to a crisp—all of these different weird frozen foods that he would eat when he was a kid and that his dad would have loved: crinkle-cut fries, pot pies, corn dogs, hamburgers—then he asked people to use those things to write on a wall—what loss they are holding in their bodies.

Ashes to Ashes, Timothy Firth, 2016. Timothy burnt all the foods that reminded him of his dad.

Participants at Timothy’s meal were invited to write was loss they were holding on to a wall with the burnt food.

MP : Yeah, I loved the way [Timothy’s] went; I found it very meaningful.

EJO : I think your meal was actually one of my favorite meals and I think that you had the benefit of being the last person to do it. Also, you and I have collaborated before, so I feel like you were ready to be like, “Ok, let’s do a reenactment and let’s make this really meaningful”. It felt more like performance art than a straightforward dinner.

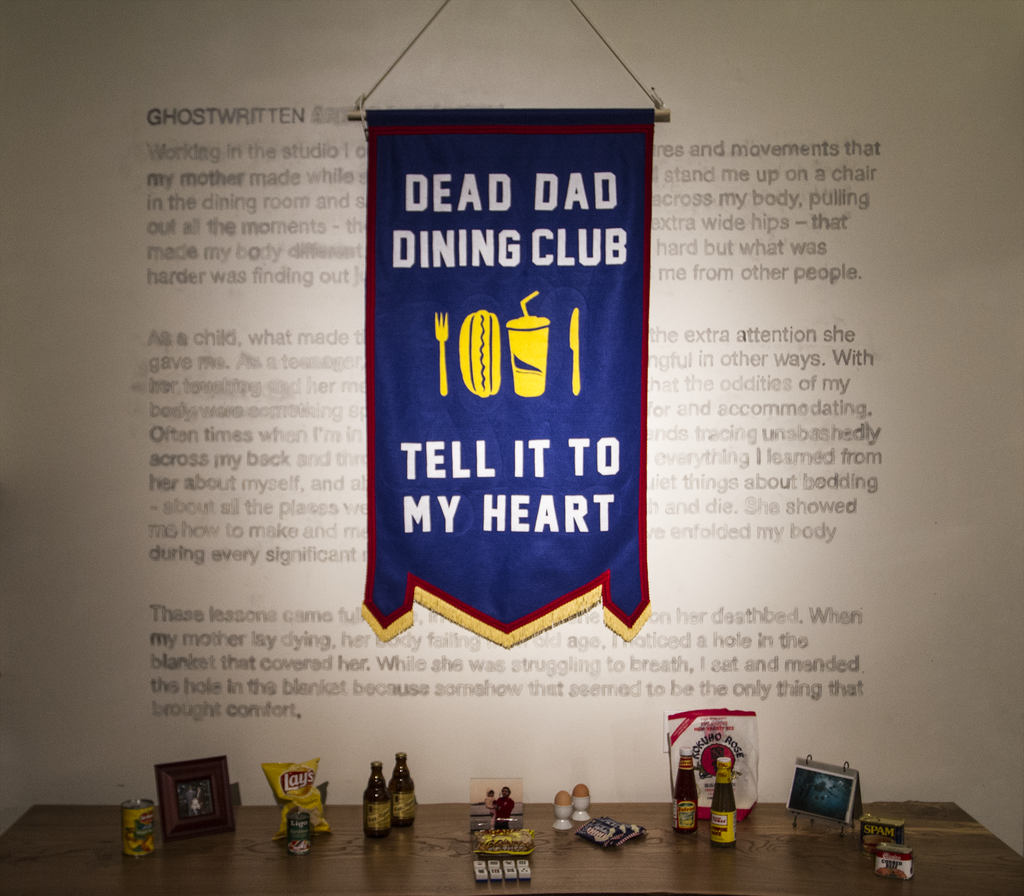

What I thought was really special about yours was the simple details of creating the space: putting tape on the ground to make parking spaces for people to sit side by side and reenact the idea of going to a drive-in and getting – y’know – chilli cheese dogs at Sonic like you did with your dad and drinking cherry limeades. The act of opening the bag and people unwrapping the fast food. Also, how you put stories of your dad in the bags so that people could go around and read aloud memories of your dad. Hearing those memories shared around the room really created a picture of who your dad was. And, then, how it ended, where everyone got up and danced to the Taylor Dayne song, “Tell It To My Heart”. The same song that was in the video we’d been playing all evening of you dancing with your dad as a child. That was really, really magical.

MP : Yeah, that was really awesome. I was really glad to have done it.

MP : So, why a dining club?

EJO : I’m really interested in encouraging conversations about difficult things, things that we don’t normally want to talk about or even acknowledge. I feel like art gives you a couple of tools to help address things like that. Beauty, humor, narrative are great anchors to bring people in and get them to open up. And so, for the DDDC I was thinking of it as a club because it is an actual unofficial club that none of us want to members of, but are members of. I wanted to highlight that everyone is bonded together over this kind of special handshake, silent wink of knowing what it’s like to have a deadbeat or dead dad. And understand what that loss is, and how we hold it in our lives. Then the other thing I was really interested in was trying to aestheticize it, without diminishing it? How to make it feel safe for people to come in and participate? I liked this idea of a club, and I was like, it would be fun if it was a stodgy, old stinky man’s club.

MP : We should have hats, like Shriners!

EJO : Yeah! I was going to make little pins, like letterman’s pins and I still might, but I was just thinking about those Elks club banners and those old Rotary Club banners and how there could be a Hall to commemorate the dead patriarchy or something. And so I was interested in playing off of that, and the old Norwegian church potlucks I went to as a child. I made one banner for the original potluck and people said they really loved it and so then I had this idea to make a banner for every meal… and Gail Grinnell was like, “you have to do it,”

Dead Dad Dining Club, felt banner, Eric John Olson, 2016. Memorial table set for Eric’s dinner.

MP : So, there is a Dead Dad Dinner Club banner for every meal?

EJO : Yeah, they’re all up at MadArt Studio right now. There’s one for every meal except one where the host didn’t want a banner made; I think it was too sad for her.

I really liked the idea of making an object that allowed people to imagine what the meal could have been like to go along with the story…

Image: James Harnois, Banners left to right for: Anne Blackburn, Michelle Peñaloza, Timothy Firth, Norah Kates, and Sara Lee Coleman with Rachel Ravitch.

MP : I think the banners really do that, I think especially Timothy’s and mine. I feel like my banner captures what my dinner was like.

EJO : I’m really interested in this idea, well, I guess it is part of being interested in social practice, right? What makes this series of meals different than any series of dinners? What makes this project different than just “I have a project that’s mine…”, whose sole authorship lies with the originating artist.

I think in doing things that are socially engaged, what makes them most meaningful is figuring out how to give agency to the people that you ask to participate; how you collaborate with them and make it feel really meaningful to all of the people involved. There’s a slippery slope in working with people and “using” people to make your artwork; it can be completely unethical or slide easily into something really uninteresting to me.. But, I’m really inspired by this balance of a cooperative practice and its potential for all participants. At the same time I don’t think good ethics alone makes a good artwork… and also there can be problems if you say everyone has the agency to do anything. You can get something that is very weird, sloppy and kindergarten-like…y’know?

MP : Yeah, there has to be a hand in curation—

EJO : Yeah, you start with this lens, this idea that you ask people to contribute to, but then each piece, they’ve authored. I’m there trying to help push them to think about it inside of a gallery space, to think about it in the context of a conversation… but, overall, I just tried to do everything I could to support those ideas, in hopes that the people who hosted the meals would be really invested in and feel agency and ownership in it. That to me is what makes the best project. It makes the best thing because we have created a space and a clear lens to examine these things that we are all holding on to and together we can shine a light on them and say they are important and that we should create more space for this type of work, this kind of therapy, you know, so… [mumbly] maybe I’m rambling, too much artspeak…

MP : Naw, you’re fine. This project is probably one of my favorite things that you’ve done. I think it’s an amazing project. How do you feel about it? Does it feel like that to you?

EJO : It feels good. I mean, I’m proud of it.

MP : You should be! I think it’s a really, really beautiful project. As a participant hosting one of the meals, one of the things I thought was an interesting experience for me was the meals being open to the public. Y’know, my father’s death, the loss of him, is such a hugely personal thing that. It ended up being amazing, but at first, I was just planning the meal and I didn’t really think about how there might be strangers there… And then they were there and I felt weird at first, but it was totally fine. And that, that’s very interesting to me too, because I had several people that I didn’t know at all come up to me after and say “Thank you so much for sharing your dad.” I feel like it was new and interesting and odd and good to introduce my dead father to strangers and really beautiful, too. I don’t know if it is like this for you, too, but I find one of the ways this loss hurts for me as I get older is the fact that people I love will never get to know my dad, you know? Like, my partner will never, can never know him.

EJO : Yeah but hold him with you, you keep him alive everyday. How do we share that without saying, “Oh, look at my photobook” and “Hold my grief and loss with me.”

MP : Yes. How do we make it about our dead—remembering and celebrating them—

and not about the pain we carrying in losing them.

Sonic Chili Cheese Dogs & Cherry Limeades, dinner by Michelle Peñaloza, 2016. Banner and memorial table for Michelle’s dad.

Chili cheese dog being eaten by participant at Michelle’s dinner.

Participants sit side by side in yellow tape designated parking spaces to reenact a Sonic Drive- In experience at Michelle’s dinner.

The Usual Window

The Usual Window

7 Poems for 7 Days

January 1st – 7, 2017

Sunset to Sunrise

viewable from outside El Capitan Apartments

Positioned where Melrose and Yale avenue meet

look up and out east

The Usual Window not only refers to the return of Vignettes Marquee to its original location, but also a childhood bedroom window, where the voyeur next door was often to be found, peering.

Valuing privacy over being seen, I cultivated techniques to disappear my body and exist only in words.

Text is my avatar.

I place my alphabet self back in the window for the first 7 days of January, each day new text in the marquee and an edition of 10 letterpress printed poems of that day, which I will give away on my usual routes through the streets.

See you there.

Bonus Track ‘ DEFLOWER THE PATRIARCHY’

www.bremelopress.com