JF: Last I heard, you were sharing a studio with Joe Rudko. What impact, if any, has this had on your work? Do you guys collaborate at all?

MC: Joe actually recently moved into a bigger studio a few feet down the hall from me. It’s a big boy space. There’s a couch in there and everything. You can do some pretty big dance moves in there.

So now I’m actually sharing the studio with Colleen RJC Bratton and the three of us have our cool little corner of the building we rent at. I haven’t actually collaborated with either Colleen or Joe yet, but being in close quarters as all of us work has been totally impactful. I always enjoy observing someone who’s good at their craft and learning by watching. We all work in really different ways with vastly different materials, but really that’s the perfect environment to be in. I think that no matter what, you pick up pieces of your peers’ workflow and sensitivities when you’re around each other enough.

JF: What drives your specific selection of non-photo materials? Concrete versus plastic, versus other materials?

MC: Odds are if it looks cool I’ll probably want to use it, but it’s never that easy. I factor in cost, accessibility, relevance to the idea I’m working with, conceptual importance, but a lot of it stems from basic innate interest.

JF: There’s not much writing on your website. No artist statement, etc, leaves reading your work wide open. Give me a haiku describing your work.

MC: You wish to know more. I wonder where I should start. Whoops, no more words left.

Just kidding, here are two:

Everything held up

flat like plywood-backed cut outs

I inspect the bones

An image is made

and rather than let it be

I force it to fight

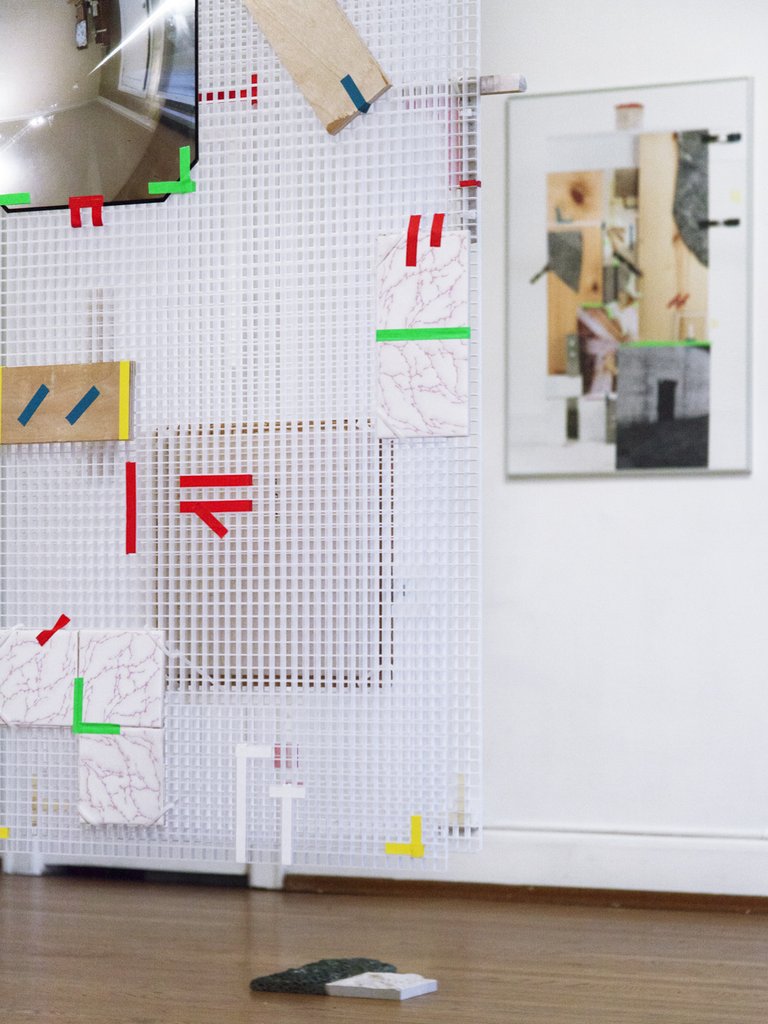

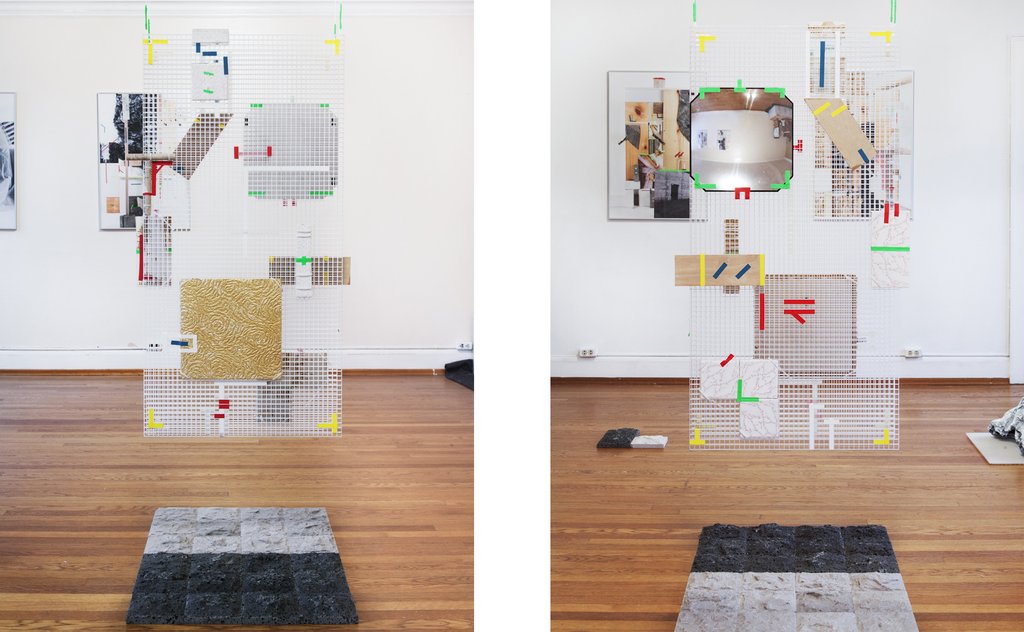

JF: In exhibition form, you engage deeply with the exhibition space — prints are not only on the wall, but displayed as hanging sculptures, pieces on the floor, etc. Why is this important to your work?

MC: I really like being entertained by art. Regardless of whether it does more than be a piece of art, if there’s something inherently entertaining about a work that I’m experiencing, I have a good time. If you can arrive at that entertainment point within the first few seconds of seeing something, I think that’s a huge success, so I try to include that sentiment in a lot of my work and exhibitions. I think when you form a photograph into an object or take it off the wall and show it outside of its established home, it turns into a character. It becomes an object that gets to occupy the same space as the viewer. They have to deal with it in their space and change their field of view to get to it. It’s a way of pushing viewers to interact more with the work, to be more conscious of themselves in the space, and also to create an environment that’s more dynamic and interesting to be in. I also use exhibition space to reinforce repetition and incompleteness, which are two of the main themes that drive my work. I try to create a rhythm between the installation pieces and my images that forces them to compete with each other, where neither side is obviously more important than the other. So in a sense every thing that I include in an exhibition is only part of a whole; while the pieces can visually stand alone, everything is complementary and you need to take it all into account equally to fully piece together what’s going on.

JF: You mention having a “long standing fascination with the built world.” Where do you fit into this personally?

MC: Well we spend most of our lives within it, surrounded by it, and dealing with it.

It’s vast and awe inspiring. It’s simultaneously understandable and shrouded in mystery, a problem starter as well as the place we gather to fix that problem, physically astounding, almost unbelievable, but created by hands and hard work.

There’s just a lot to unpack about the structures and spaces around us and while it’s always been of interest to me, lately the built world has fueled so much of my work. I worked for about a year as a real estate photographer and recently my freelance work has granted access to a bunch of mid construction towers, apartments, and commercial buildings. So I’ve been able to experience and observe a lot of what goes into development and the selling of spaces and that’s really what interests me. Everything from home staging to the marketing vocabulary to the presentation of the images I was taking, it’s all part of a giant production and the work I’m making is my way of mining through it all and figuring out what it means.

JF: In the text for your recent exhibition Crushing Sensation, you mention the “Spectacle.” I pretty obviously jump to Guy Debord. Are you a fan?

MC: Yeah absolutely. Society of the Spectacle and Jean Baudrillard’s Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared have been immensely influential to my thinking about art, images, photography, and representation in general. I’m really grateful to have had friends pass those texts along to me. We could get really into it, but I’ll sum it up by saying that between the two texts the ideas that we no longer have real experiences, that we live for and through representations, and that digital means overtake the importance of the original they reference have had major influences on my work and life.