Essay by Gretchen Bennett | Photographs by Sierra Stinson

Life is Beautiful

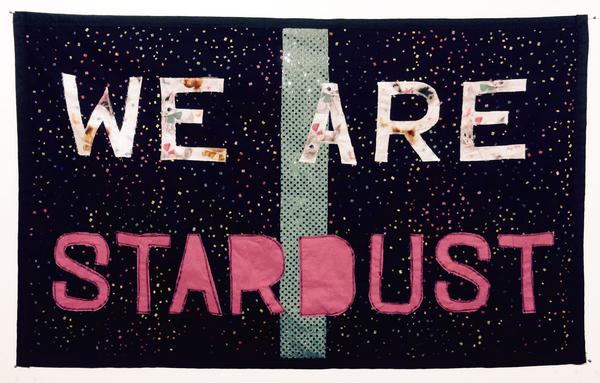

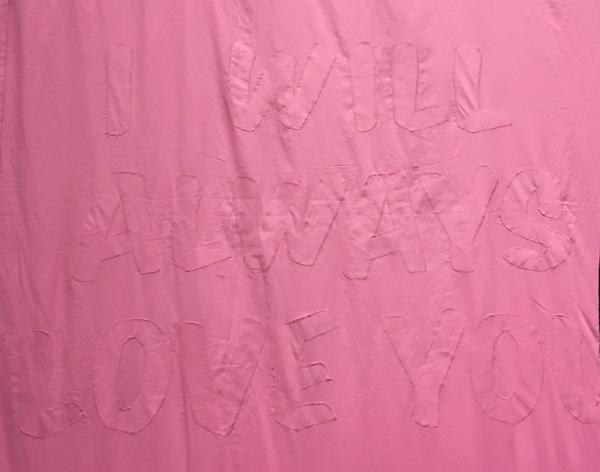

Joey Veltkamp is exhibiting a new quilted work, Life Is Beautiful, at the Tacoma Art Museum. The quilt, constructed of stitched batting and fabric and around 11 feet square, is his largest to date, collecting 12 different song lyric fragments under the banner of Sufjan Stevens’ lyric, We’re All Gonna Die. Titled Life Is Beautiful, the work was created for the TAM for its exhibition, NW Art Now, running May 13 to September 4, 2016. Joey’s TAM entry, while acknowledging our mortality, is also hiding hopeful song lyrics, embedded pink on pink in the body of the quilt, asking us to hold on. This quilt could be lifesaving.

Joey describes his quilted work “as existing on the edge between hopeful and bleak, candy colored sadness. One side is comforting,” an expanse of pink; “and one side is real,” appliquéd with We Are All Gonna Die. The comfort is also real.

Maybe the making of the work brings clarity to the artist, as he uses soft materials to face harder realities. The avoidance of this labor would be understandable, but Joey has said that making the work is compulsory for him and it gives him relief.

An example of the two-sided nature of his work is Old Sun New Day, a quilt made in 2015 to commemorate a friend’s death. White text is stitched onto bright sunrise—and sunset—colors. An archived Arts West website entry describes Joey’s fabric work as having “themes of comfort, social and political affirmation; dealing in Northwest mythologies, feminism, gender identity, quilt history (The Gee’s Bend Quilt Makers), (art quilt history: Faith Ringgold), The Carpenters, and queer politics. Aphorisms like “A day without lesbians is like a day without sunshine” are meant to replace worry with comfort.”