an informal review of solo exhibit “Well” at Glass Box Gallery, January 2016 | Written by MKNZ

Open Letter to Maggie Carson Romano

Maggie,

I wish I could tell you exactly how many times I’ve thought about this show; how many times I’ve thought about the body healing faster than the soul; how deceptive that is.

I was going to write a ‘review’ of your show. I tried to write a review of your show, as that is what Sierra asked me to do. But I fear I’ve had too many conversations with you to remain objective.

I had a dream shortly after you left for California. I was eye level with a black, lapping ocean. So dark that all I could see was the moon reflecting off the peaks of the ripple. When I raised my hands out of the water they were covered in a film of blood. I touched my body all over looking for the seam and found the smallest opening in my stomach, leaking slowly and steadily, but I felt no pain. I looked up at the sky and found it framed in a circle; I was in the bottom of a well, the liquid from my body bringing the water level slowly closer to the surface.* Briefly, I feared I would run dry before I reached the top. But I could feel my heart beating from the pulse behind my ears and it was strong and steady.

When I came to your show on opening night, the room was full and quiet. Those of us who discovered the handouts of your accompanying text were crying, looking for others who had just finished reading it, and then crying with them.

As I told you in the car that day, to me, the show was your letter. All of your pieces were its girth; its lofty, solemn evidence. Most especially, the shattered ceramic fins. How did it feel to hold that shape in your hands? To run your finger across its edge? I wonder if they make your blood run cold or if their cracks brings you some solace. There is a sameness to many of the textures in your show: the sliced pear, the tear in your cheek, the cracked fins – there is a comfort to their shared fragility. Everything can be bruised, splintered, melted down, pulled apart. And isn’t this what we are most drawn to? Doesn’t a tree just seem like a tree until its branch snaps and dangles helplessly? Isn’t it in those moments that we bestow it with humanity?

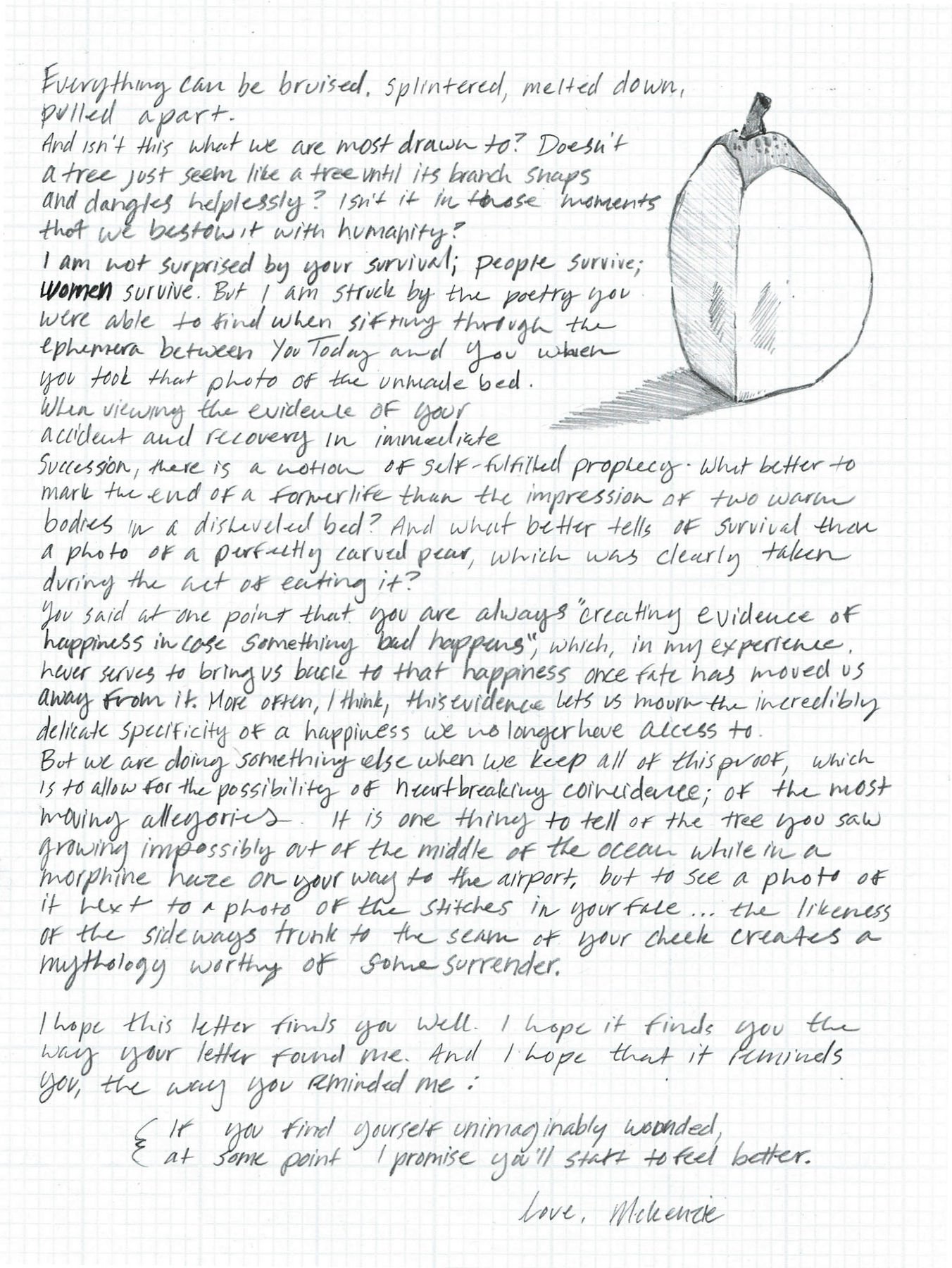

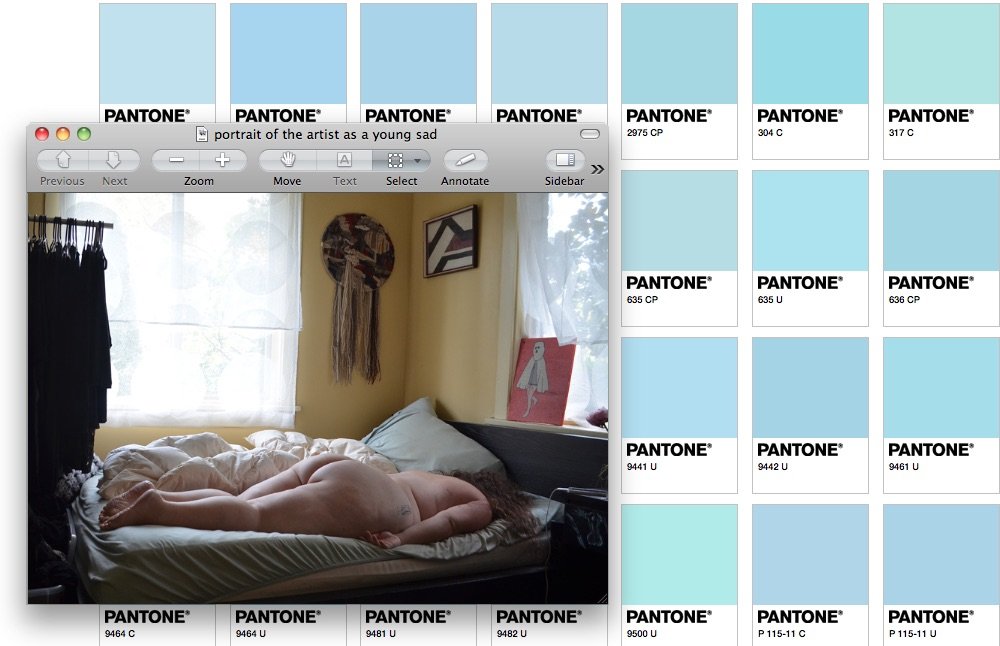

I am not surprised by your survival; people survive; women survive. But I am struck by the poetry you were able to find when sifting through the ephemera between You Today and you when you took the photo of the unmade bed. When viewing the evidence of your accident and recovery in immediate succession, there is a notion of self-fulfilled prophecy. What better to mark the end of a former life than the impression of two warm bodies in a disheveled bed? And what better tells of survival than a photo of a perfectly carved pear, which was clearly taken during the act of eating it?

You said at one point that you are always “creating evidence of happiness in case something bad happens”, which, in my experience, never serves to bring us back to that happiness once fate has moved us away from it. More often, I think, this evidence lets us mourn the incredibly delicate specificity of a happiness we no longer have access to. But we are doing something else when we keep this evidence, which is to allow for the possibility of heartbreaking coincidence; of the most moving allegories. It is one thing to tell of the tree you saw growing impossibly out of the middle of the ocean while in a morphine haze on your way to the airport, but to see a photo of it next to a photo of the stitches in your face… the likeness of the sideways trunk to the seam of your cheek creates a mythology worthy of some surrender.

I hope this letter finds you well. I hope it finds you the way your letter found me. I hope that it reminds you, as you reminded me:

If you find yourself unimaginably wounded, at some point I promise you’ll start to feel better.

Love, McKenzie

*(later, I would re-read your letter from the show to discover the line “deep down somewhere you cracked and everything leaked out to somewhere else” and wonder if that line had situated itself deep inside of me)

Dear Jenny, We Are All Find

Authors, Publishers and Readers of Independent Literature (APRIL) and Vignettes unite for a group exhibition inspired by the poetry and words of Jenny Zhang’s Dear Jenny, We Are All Find

Reading by Jenny Zhang

Location: Indian Summer

Artists:

digital print, cotton t-shirt, bleach, fabric paint

c-print, edition #1/10 +2AP

Peaches, Cream, Infinity Mirror, Lucite

Acrylic, Enamel, Primed Canvas

digital archival prints

portrait of the artist as a young sad

Kim Selling

May 12, 2016

8:45pm – 10:45pm

Outside of El Capitan Apartments

North side of the building near the Olive Way 1-5 overpass

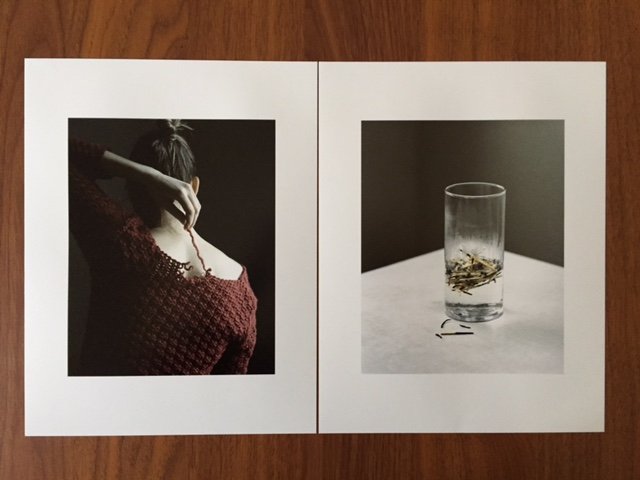

anxiety is a self-restacking pyramid of plastic ice cubes forming the arctic ziggurat of your spinal cord. it reaches so far and so high it can almost count as pre-workout stretching because stress is exercise and your entire body is awash with pain. this body feels lived in; it is indented with the fingerprints of each resident — cracks in the glacier widen each day to show new rooms, soon to be inhabited by old triggers.

this anxiety guilts you out of bed down the stairs out into the sunlight into a bus out of the bus into the sunlight. you obsess — is it still a panic attack if it’s just your entire life? the sunlight holds hands with your anxiety; they muddle, and birth shame, which pushes you, like a pug on a skateboard, into the nearest building that has coffee. and sometimes you’re stretching in line at a cafe and the human behind you asks a question, so you turn around, but you sneeze mid-turn and throw your back out, and you think, why did i ever walk downstairs.

Rumi Koshino | Red and Blue

Essay by Colter Jacobsen | Photographs by Maggie Carson Romano

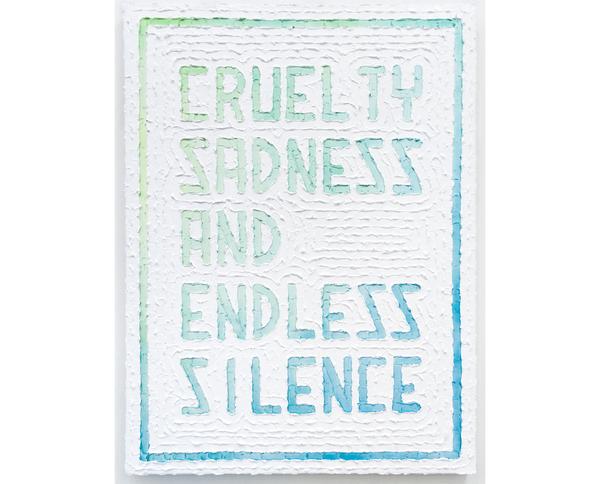

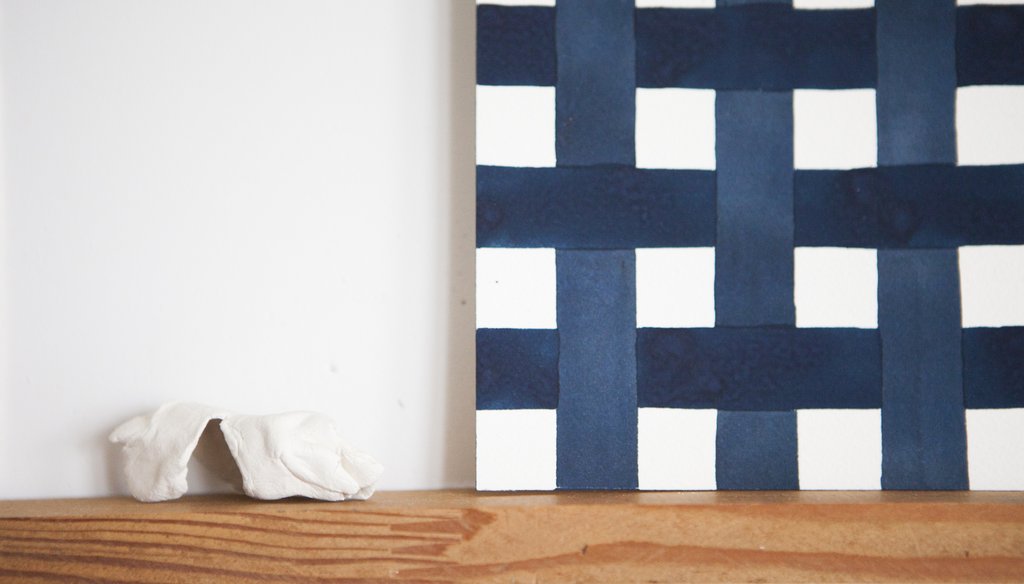

Drawing and painting can be a very intimate thing. I found myself thinking this at a recent music show where the artist Rumi Koshino was projecting a collaborative video accompanying live music. A video camera had been set up to record in real-time Rumi’s watercolor composition while she painted slowly and deliberately. The live-feed was projected behind the musicians onto an accordion-like backdrop reminiscent of a Japanese screen.

There was something absolutely hypnotic about watching one color run into another. A red brush stroke slides across the paper, meeting a blue brush stroke. The two rivers collide in cataclysmic purple. It’s a gesture made by an artist but nature takes over in the wake. The surface of paper becomes a floodplain where the edges of least resistance burst into expanding rivulets.

I noticed that Rumi seemed unconcerned with the final outcome of the image: she used liberal amounts of water. Her marks felt close to music, a present-tense gesture/mark of the moment. I read into the two colliding colors as human relationships. I fell in love with a brush mark that was suddenly obliterated by a grey pool…jolted by the fleeting moment of it.

How quickly we, as viewers, read into the marks and movement. Every mark is a decision, every nuance is connected to a brain synapse. And it’s this exchange, from the artist’s synapse onto a picture-plain to our receiving synapse, which is so mysterious. What is it about our human nature that projects narrative and emotions from simple colors, shapes and lines? I am reminded of the poet Philip Whalen describing his own poetry as “a picture or a graph of a mind moving, which is a world body being here and now which is history…and you.” The dual projections of sending forth and receiving go back even earlier than shadows bouncing on Plato’s cave.

The word project comes from the Latin, projectum from the Latin verb proicere “before an action” while projection (mid 16th century) has the same Latin root as project, yet it’s meaning is to “throw forth.”

I think of the tapa cloth drawings by women of the Maisin tribe of Papua New Guinea. They don’t have a word for art, per se. The closest word they have is Saraman, meaning “think & do.”

Rumi recently completed a project that consisted of making one drawing per day for 100 consecutive days. In a Facebook post, she stated, “I started my first 100-day (sculpture) project on this day, February 18th, 2015, prompted by Debra Baxter. Somehow, it feels perfect to finish my second 100-day (drawing) project on the same day, a year later, completing a circle.”

From such an approach, certain qualities tend to come to the forefront: looseness, lightness, quickness (see the first essay in Italo Calvino’s Six Memos for a Next Millennium). A daily practice also keeps your chops up.

Rumi has lived in San Francisco for about two years. She moved from having a large live-work space all to herself in Seattle to a flat in San Francisco with three roommates. She has a small room and one closet. All this to say that she has substantially downsized. There is a new economy to her drawings. The word economy comes from the Greek, meaning “household management.” Can this system of daily drawing be a way to keep order in her household, and for her general mental stability? Even with such a small amount of space, her room still feels sparse. Only a few of her 100 drawings are displayed at one time. All of her “sculptures,” most of which were collapsible and made of paper, are tucked away somewhere.

Through the 20-something years that I’ve know Rumi, I’ve seen her work morph into all kinds of different sizes, shapes and themes. But even small, the scale can feel gigantic.

I remember the earliest works I saw of Rumi’s depicted very basic things: toes of a foot, a light switch, a house or I should say a home. Dwelling on the theme of home certainly made a lot of sense seeing that she had just left Japan to study in the U.S.

One particular painting I recall was a line of various colors in the shape of a rectangle that ran along the border of a rectangular white canvas. She said the line represented a road trip she had taken and each color represented a part of the trip. This road trip still lingers in my mind as a wonderful alternative to mapping time and space. I see it again in several of her 100 drawings.

Later came ladders and then bridges, many bridges, broken bridges, bridges that led from nowhere to nowhere, emerging out of an ocean, taking the viewer from one area of water to another area of water. The bridges of two cultures seemed the obvious metaphor though the more she built them, the more I think they actually were about the bridges of relationships, the bridges between any two people, no matter their culture, trying to communicate with each other.

The bridges eventually disappeared as if completely consumed by the ocean. And only the marks of water remained, vast oceans of marks. For her final show in Seattle she invited friends over to cut out envelopes from a very large-scale drawing of an ocean surface. The envelope, as an abstract bridge of distance, from a here to a there, is also a gesture of giving that, in turn, implies a return.

She can effortlessly alternate between abstraction and representation, the two often in dialogue with each other. This can also be said of her 2-dimensional work and her sculptural work. Both point back at each other. A drawing seems to play with being 3-D while a sculpture flirts with 2-Dimensions.

Since moving to the Bay, Rumi has been a little more light and playful. She tends to absorb her surroundings. Her skin membrane is porous. Patterns from her environs find their way into her drawings while strange interior, cellular-like shapes float in to disrupt the patterns. The ocean is still hanging out too, sometimes in the shape of drapes while clouds float through doors. And triangles continue to hint at envelopes, circles designate absence or eyes while pairs and symmetry are never too far off…

When I first met Rumi in a Color/Light/and Theory class, I remember looking at an art work with her. In the composition were two squares, one blue, the other red. We were casually talking about the piece when she pointed to the blue square and said “red.” It

was her first year in the States and I assumed that she was still acquiring her English skills. So I corrected her and said “blue.” She shook her head and again said “red.” About to repeat my blue, I took a look at her straight face. It finally eased into a smile and again, she said “red.” She was playing with me. Not only were her English skills advanced, but she was turning the world on its head.