Essay by Willie Fitzgerald | Photographs by Eirik Johnson

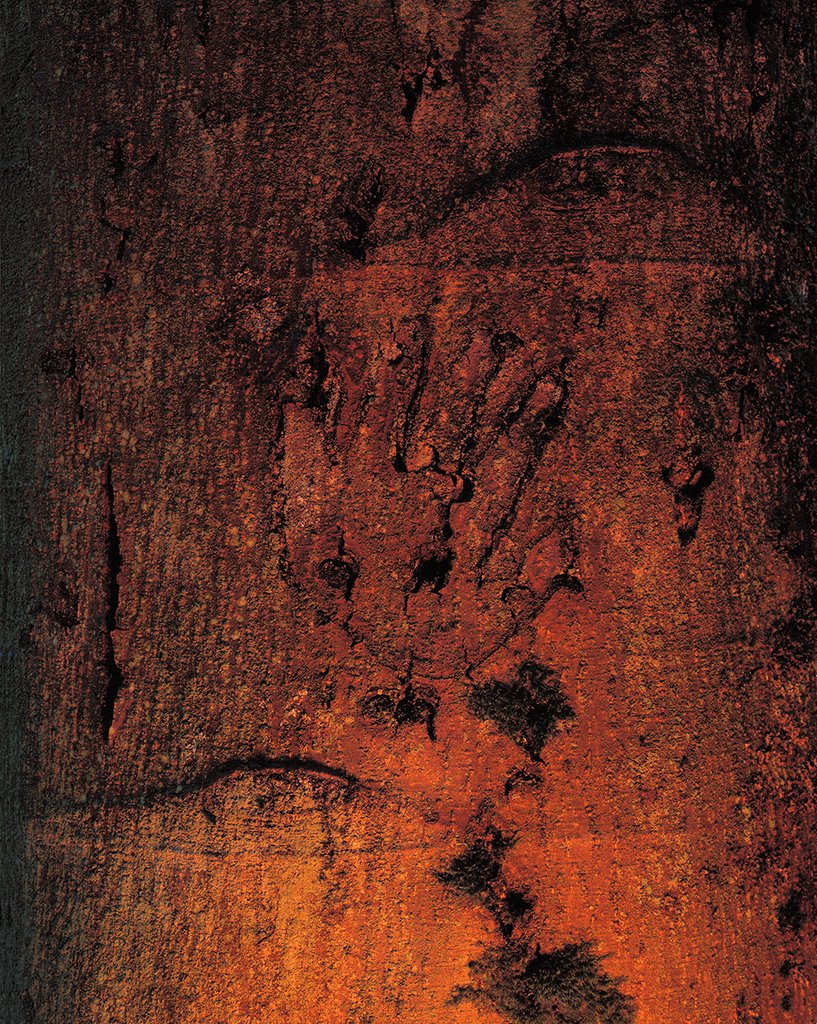

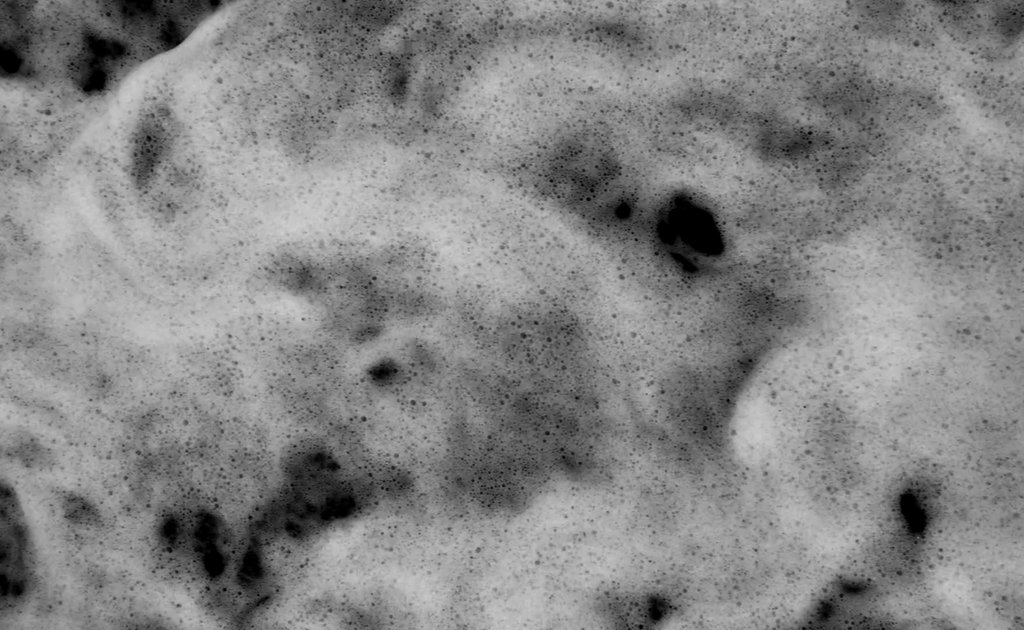

Just south of Cle Elum there’s a swath of forest where hundreds of burnt pine trees dive into the sky. A fire raged there sometime in 2014, one of so many that summer. Now the area is a moonscape, a graveyard, a monument. It’s also where the multidisciplinary artist Zack Bent has been working for the past half-year or so, arranging sculptures and photographing them alongside his wife, the artist Gala Bent, and their three sons.

Doing a “studio visit” with Zack Bent is a bit of a misnomer. Yes, Bent and I talked in the space he shares with his wife (it’s in SODO, in the shadow of the iron tortoise shell of the baseball stadium; there are racks of lumber for the sculptures Bent makes, and a work table covered in Gala’s colorful, complex paintings), but Bent makes the majority of his work on location.

Like this forest fire in the Cascades. The photographs Bent has been shooting there will be part of his solo exhibition “Spires”, which opens at the Seattle Pacific Art Center Gallery on January 21st. In one photo Bent’s family stands near some bone-white wooden pyramids. In another, Bent’s son regards a black canvas strung between two burnt trees, a makeshift tent slackened into loose strata. In yet one more, taken sometime over the summer, his sons and his wife kick up a small cloud of ashen dust.

The Bents are out of place in this black and gray wasteland, but many of the photos still exude playfulness, joy, a sense of motion temporarily suspended. Some, unsurprisingly, take on a more somber mood. There’s something unavoidably apocalyptic about the juxtaposition of this towheaded child and the scorched landscape. It feels reverential and foreboding. That could be just oversimplified symbology—forest fires are also opportunities for new growth and rebirth; Bent found this site when foraging for morel mushrooms, which frequently grow the spring after a forest fire.

Even in this wild—and wildly fraught—setting, the object of Bent’s artistic investigation remains domesticity, the home and the family unit. (His children are wandering through an ashen scar in the Cascades, but they’re still his children). Bent is curious about the myriad small things that happen in a domestic space when we aren’t looking at them, the moments of stillness and silent progression: “What happens if you just stop? What happens if you’re a photograph?”

A few of his older pieces take this idea of long focus to an extreme: one jar of honey empties into another, a viscous hourglass. In another video, clear rendered fat begins to whirl as it hardens to opacity. I remember a piece that Bent made for “In The Absence of…,” a group show at the Greg Kucera Gallery curated by Klara Glosova and Sierra Stinson. Bent made a video, playing on a loop on a flatscreen TV, of a young boy alone in a forest (“Heavy Matter I”; there was also a platform made from blackened logs placed in front of the video, in retrospect an obvious prelude to his current exhibition). The video defied its own medium—nothing seemed to happen. And then I looked closer. The boy was swaying slightly, trying to hold his pose. It was this attempt—the approach toward stillness and its failure—that lured me in. From the TV I could hear rain falling, a soft static.

If the domestic space is the area of focus for Bent, what fuels his artistic process is the constant tension between arrangement and occurrence. “I have to put something in place where something will happen, so I can find something that can break my own system.”

Trained as an architect, it’s difficult for him to work without a blueprint. “When my oldest son was five, we did a thing at Vermillion with Lincoln Logs, and he just wanted to build things. I had to tell him, ‘You can’t just build something, we have to figure what we’re going to do and then build it.’”

But, at the same time: “I’ve always been mesmerized by really intuitive work where it just seems like things come together by chance—what I’d describe as ‘what the camera found’ as opposed to ‘what I made.’”

So Bent sets up environments where this sort of organic, unplanned moment might occur. This might be his sons’ heads, thanks to a trick in perspective, melding into one unit, or it might a particularly forlorn or enigmatic expression on his wife’s face.

It’s a process that, especially as his sons grow older (the oldest is not yet a teenager) and express more of their own personal and artistic agency, requires some diplomacy. “I’ve started to take on more of a directorial role”— I first misheard this as “dictatorial” before he corrected me—“and I’ve started to dangle more carrots. Cheeseburgers, milkshakes.”

With sculpture, it’s harder for Bent to buck against his inner architect. “To build something, I have to build it right. It has to be right. I can’t just tape up the corners and call it good. It’s just not my personality.” Many of Bent’s sculptures are made from ¾”x ¾” pine lumber and have a sturdy, geometric feel to them, like scaffolding for a building only he can see.

Bent has a reluctant, nearly adversarial relationship with sculpture. He started out wanting to be a painter, and he seems most animated when we talk about the image—the living moment as it is captured, preserved, and flattened into two dimensions.

Still, the craft of sculpture, and its material investment, is unavoidably attractive. For Bent, sculpture is more than the creation of an object, it is the process of “confounding [its] materials”—in other words confusing and expanding the possibilities lying dormant in oak, stone, or simple pine.

I think about an aphorism from the Italian artist Fausto Melotti: “The true artist does not love or respect his material: it is always on trial, and everything can go completely wrong.” Love, for Melotti, can sour to hate; respect is too cold and formal a distance. It is only in the confrontational, liminal space of the trial that an artist can simultaneously engage with and be free from their work. (That in turn makes me think of a Smog lyric: “We are constantly on trial/ It’s a way to be free”).

In this sense, Bent’s work is perpetually testifying against itself, the loose improvisation of his photography cross-examining the tight Euclidean architecture of his sculpture. Everything, as Melotti says, can go completely wrong. But for Bent, it’s in the going wrong—the sudden, spontaneous defiance against the ordered system—that the real piece emerges.