T(here) : Kathryn Fleming / Future Species

By Elissa Favero

Seattle writer Elissa Favero talked with artist/designer Kathryn Fleming via Skype about evolution, beauty, and the stories we tell about animals for Vignettes’ (T)here series. Fleming has a bachelor’s degree from the Rhode Island School of Design and recently completed a master’s degree in Design Interactions from the Royal College of Art in London. She’s currently living in and around Washington, D.C. You can see more images of and details about her work on her website, Modern Naturalism.

Elissa Favero: Okay, here we are!

Kathryn Fleming: Well, I’m very honored, by the way, to be part of the Vignettes project.

EF: Well, I’m very excited. I think this will be a really nice way to introduce you to some folks who don’t know about your work yet

KF: Thanks!

EF: So just to start, how would you talk about your work to someone who doesn’t know anything about it or hasn’t seen it before?

KF: I guess I usually start by telling people that I’m interested in…well, like how some people are interested in dinosaurs, you know, things that existed in the past and nobody really knows exactly what they were like? I’m sort of interested in the same thing but thinking about it in the future. So, what new forms of life might evolve and what would they look like and how would they behave? I tell people that I make prototypes, bringing it back to design in that way. So they’re prototypes for future species.

EF: A lot of your work has an element of responsiveness, an attunement on the part of the thing that you’re making to the way that people will interact with it. Can you talk about that and the role that that kind of responsiveness plays in your thinking?

KF: Yeah, I feel like one of the things that I want to have people think about is not just how we influence nature but how nature influences us. And I think that because we perceive so much of our interaction with nature as very dominant, we don’t necessarily always realize how connected and linked and dependent we are on other species. I’m interested in the fact that nature has its own set of motivations and its own agency. And even though we influence nature, nature can also influence and change the way that we live. So great examples are when people have developed symbiotic relationships — like with plants, for example. I think Michael Pollan did a really great job addressing how plants have had some influence on us and have manipulated us and our desires in The Botany of Desire. Similarly, in my work I think that I try to highlight capacities that organisms have that people don’t necessarily realize.

EF: Yeah, I’m thinking of your project with the fungus that responds to the environment and the way your gut process certain chemicals.

Fleming’s project Gut Reactor: What Does the Fungus Know? explores the symbiotic and aesthetic capabilities of the fictional Fungus Domesticus. Digesting human waste, Fungus Domesticus produces airborne spores that repopulate human gut bacteria to help balance the emotional health of the people living alongside the mushrooms.

KF: Yeah, totally! I think it’s really interesting to think about how we design nature as a product, but I think it’s also really interesting to think about how nature could integrate itself into our lives. So in the case of the mushrooms, well, in nature mushrooms are ecosystem stabilizers. They serve to communicate between different organisms and they even funnel nutrients back and forth so that a plant that doesn’t have as much can get from a plant that has more. And it all benefits the whole ecosystem. So I was thinking about what capacities fungus has and how they could exercise them to influence us. A lot of fungus are detritivores, so they live off nutrients obtained by consuming detritus or…poop.

EF: Right!

KF: So, if they were to live off of human waste, what kind of information might that give them about us and then how could they respond to that in a way that would be influential, not just on our behavior but on our perception of fungus as a dynamic organism? I mean the funny thing about fungus, specifically — I mean, I could talk about fungus for a long time — I mean, it’s not a vegetable, it’s not an animal, it’s this other life form, and I think we often don’t want it in our homes. So I was also trying to think about a way that fungus could become something we would be interested in having in our homes and cultivating as a living partner.

EF: I like that! That’s nice.

KF: I’m interested in how that relationship could evolve to be mutually beneficial. By providing us with better emotional stability, the fungus is then able to have a source of food all the time and also access a new habitat. It can move into our homes, which is a place that we usually don’t want fungus to be.

EF: Ah, the tyranny of hygiene!

KF: Right. The orchid project is similar.

In Fleming’s Estrous Orchid: A Botanical Investigation, the petals of an imagined orchid native to the highlands of northern Peru change color in response to the menstrual cycles of nearby women.

EF: Yes, those were the two pieces I especially had in mind with that question about responsiveness. I really like how your projects complicate or make more nuanced our perceptions of our relationship with nature

KF: Yeah.

EF: But I think these two projects in particular speak to your background in both art and design. You’re making something that’s not just beautiful or even interesting but something that would have the potential to continue to respond and interact.

KF: Definitely! I feel like in design, a big problem is when people make things and then spit them out into the world without a lot of consideration to what happens to those things. That’s also one of the coolest things about technology: you can create a technology, you can put it in a certain platform, you can release it out, but then you really have no idea what reapplications or repurposing will ensue. And I think that biotechnology freaks people out a lot because there’s that open-endedness to it.

EF: Right.

KF: When we talk about evolution, everyone refers to Charles Darwin and “survival of the fittest.” It’s looking at nature as highly competitive, in a tooth-and-claw world. But actually, I think that cooperation as an evolutionary tactic is something that’s overlooked and is potentially an even greater mechanism for evolution and one that we need to be thinking about much more since we’ve taken over so much.

EF: Going in a different direction — or maybe not — can you talk about the element of storytelling or narrative in your work? I’m thinking especially of older stories — the tradition of bestiaries — but also science fiction or speculative fiction. How would you position your work among these other forms of storytelling?

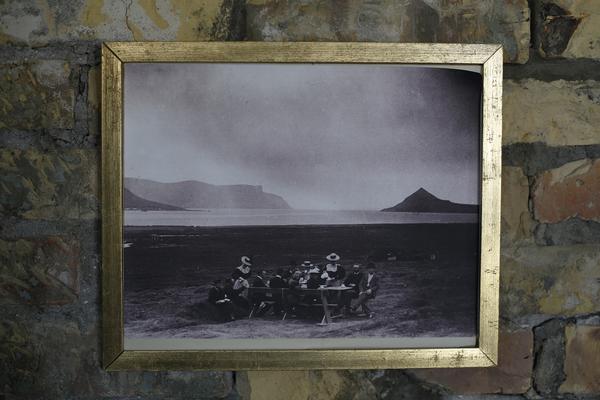

KF: Yes! That’s a great question, Elissa. Well, if you don’t imagine it, it’s not a possibility. People have a lot of anxiety about the future and uncertainty. And one of the ways that we channel that is to construct narratives that guide us and also give us ways of looking at things that we didn’t necessarily have before. So my work isn’t necessarily functional, but I want to provoke people to imagine how things could be different. So I’m not saying when I propose something that I want that thing to actually exist, but I want to open up a way of thinking that isn’t part of our normal conversation and culture. The way that humans are designing and constructing their environment increasingly, we have to talk about a whole range of possibilities as opposed to being fixated on producing the real thing right away. In terms of the older stories, like the bestiaries, I think of imagination as kind of being like an evolutionary technology; imaginary or mythical animals often embody our fears, hopes, or anxieties in a technologically changing landscape. There are many mythical creatures in cultures around the world that serve to guide our human perception and interaction with nature. Think of the “sea serpent” — accounts and sightings of sea serpents became increasingly common during the period of technological advancement in sea travel and trade. With navigation and sailing opening up the world’s oceans to human transport, the sea serpent became a cultural creation to focus our uneasiness. There are so many great illustrations of sea serpent sightings from the Illustrated London News, but we rarely see such things in mainstream media anymore. Our relationship and security with global travel has changed a lot from those days and so we don’t need the sea serpent anymore. Another example is the centaur, a creature that is part horse and part man. The artwork and imagery of these hybrids begins to arise only after equine domestication. Perhaps the human imagination needed the centaur as a way to adapt and understand the altered relationship between man and horse. This is just speculation, but I think the stories we tell about animals, especially during periods of technological and cultural changes, help to express our fears and desires and influence or guide our cultural perception of human and animal interactions

EF: In thinking about how to characterize what you do, Mark Dion came to mind. He is so great about showing us the sometimes perverse ways that we’ve organized knowledge or enacted colonialism or facilitated the travel of other species. He looks back to tell stories that have happened, a kind of archaeological practice. You’re interested in very similar subjects, I think, but you look forward.

KF: Well, first of all I’m honored by that comparison. Yeah, I just get excited thinking about what the future might hold. I also get sort of sad – am I going on too long?

EF: No, this is great!

KF: Sad because I think my work is, well… So after the Jonathan Jones piece from the Guardian was published, and he talked about my work as being “wicked,” well my work in my mind is not like that at all. It actually is sort of sincere in terms of these proposals. It’s because I’m desperately trying to imagine a way that there could be that sense of discovery and pleasure in nature continuing into the future, because we live in this age of extinction, so we’re watching all these beautiful things disappear. And as a designer, I want to try to imagine how there could be new things. How can we design the future of wilderness?

EF: Yeah, I wanted to ask you about wilderness because I was looking at that piece from the Guardian. Jones seems to alternate between outrage and confusion as he considers your work. But when I was reading it, I was reminded of an article from the New York Times from last summer, “Rethinking the Wild.” It was all about a changing approach to wilderness. The Wilderness Act was 50 years old last year, and there’s some reevaluation about what its future should be. In light of climate change, the way that we’ve thought about our role as guardians instead of gardeners of wilderness — in line with the act’s original intent — well, that might not be appropriate anymore. That won’t be enough.

KF: It’s not a sustainable model.

EF: Right. And the author, Christopher Solomon, gave a lot of examples, like the trees at Joshua Tree Wilderness in southern California. If climate change continues as scientists predict, 90% of those trees could be dead in a hundred years. So is it appropriate to let that happen or are there ways to be more hands-on in our management? Like relocating the trees. The article does a great job opening up discussion about how to reimagine our role in a world that we’ve already influenced so much.

KF: Yeah, I think if it were me, I would try to hybridize the trees with plants that are drought-resistant.

EF: That was another idea!

KF: I was watching this trailer for a Kickstarter called “The Last of the Longnecks,” and it’s about the silent extinction of giraffes. We have a tendency that when we can’t see it, we think that it’s okay. I mean, most animals live in our imagination anyway and we don’t actually encounter wild animals that often. So as long as you’re seeing them on TV and they’re still in books and on tote bags, it seems like everything’s okay when in reality large mammals like the giraffe have no place in a human, modern world. I think that the sense of awe and wonder that you get when you see something like a giraffe, what happens when that disappears? What happens to the way we think about the world and perceive things and perceive possibilities? It reminds me of what happens in cities when you can’t see the stars. There’s something really important about experiencing something that seems impossible or beyond what you could imagine.

EF: Yeah, I see your work as not a way to diminish the mystery about those things but instead to figure out other ways to cultivate that mystery.

KF: Yeah! Totally, totally.

EF: Okay, good!

KF: Yeah, one of the things that I’m most excited about that I’ve been reading about is new research into microbiology, development, and genetics. One of my favorite researchers and authors on the subject is Sean B. Carroll. He has written about the new science of “Evolutionary Development” that brings together the fields of evolutionary biology, embryology, and genetics to explain the incredible variation of shape, form, and behavior that we see in nature. This is one of the oldest questions out there — it’s like “How did the leopard get its spots and the zebra get its stripes?” Well, the new field of Evolutionary Developmental biology can actually explain how. Before Evo-Devo, no one in biology thought that we shared the same developmental genes with other creature — but they were dead wrong. In fact, most of the genes that govern fruit fly development have exact counterparts in other animals, including humans. The development of an eye in a fly is caused by the same gene that causes the development of human eyes! These “body-building” genes are known as homeotic genes or “hox” genes — and they cause the development of functionally similar features in a huge variety of animals. This discovery/understanding highlights an incredible symmetry that exists all through nature. And it’s not just eyes, limbs, and hearts that work this way. In developmental biology, they talk about having a “body plan” and “body design” that is basically determined by hox genes switching on and off during different phases of an organism’s development. These things are elemental! So if hox genes are the fundamental tools and building blocks of emergent biological design, what else could they generate and for what purpose?

EF: Are you ever worried about people whose intentions aren’t as, well, good as yours? Like the possibilities…

KF: That’s already happening. Have you seen Belgian Blue cows?

EF: No.

KF: Would you just Google that?

EF: Sure.

KF: I mean, the weird thing about the whole agricultural-industrial complex is that there are all of these new species being created. They’re not represented in natural history museums. No one except for the people who work directly with them ever come face to face with them. No one wants to talk about that, but that’s nature

EF: Wow! These are crazy.

KF: These are crazy.

EF: They’re so beefy!

KF: Yeah

EF: Wow.

KF: And that’s just artificial selection.

EF: Wow, they look like sculptures.

KF: I know, it’s like their muscles have muscles. They’re like creepy body builders.

EF: Or Michelangelo’s nudes. Like where did he get those models? Like who was he drawing from? Or was he just so aware of anatomy that he could say this muscle is here and could eventually be giant, you know?

KF: I think it was a bit of both because he was an anatomist — he did all those dissections and drawings of the human body.

EF: Yeah.

KF: So this stuff, what you’re talking about and what you’re worried about already exists. And the ethics of this whole thing are part of what I want people to consider

EF: To grapple with, yeah.

KF: To grapple with, because I would love to have a museum where all of these modified animals that we’ve created exist. Or all of the dog species that we’ve evolved in the last 100 years. Most of them have been in the last 100 years! Whenever I look at a dog I think that is not nature, you know, that is humans. But we love dogs. We never think of them as being something that’s unnatural.

EF: You’re right. They’re engineered by us, but they still have mystery. They’re still their own entities.

KF: Autonomous beings.

EF: Autonomous beings. Can you talk about the role of beauty in your work?

KF: Yes. Shared aesthetic sense is something that exists not only among humans but also among species. Like we find birdsongs beautiful, and birds also find those songs beautiful. And so there’s this idea of an aesthetic or an art-world. In terms of evolution, there’s natural selection but then there’s also sexual selection, and that is really what determines the unique aesthetic of any species. The more competitive sexual selection is the more ostentatious and crazy the adaptations and displays become. And there’s not really any reason that they’re there. The peacock doesn’t need it. In fact it’s more of a hindrance. But the female responds to it. She finds it beautiful.

EF: Yes, speaking of responsive design!

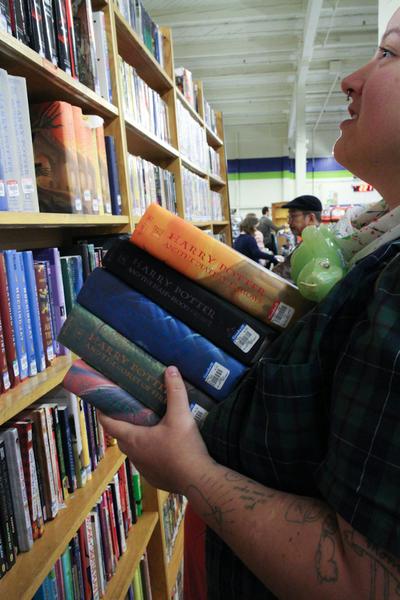

KF: Yeah, and isn’t that kind of an artwork? Like when Bowerbirds build nests, these really crazy nests. You should google “Bowerbird nests.” And they like to collect things that are all blue, and they do this just for the female. But are these not artworks, are they not things that these animals are creating as an aesthetic expression for the pleasure of another animal? So I think that beauty is a great mover of attraction, of evolution. And I think it can also be a really powerful tool because it is something that as living things, we all intrinsically share a lot of aesthetic sense. And when you think about it that way, the extinction of a species isn’t just the loss of life but the disappearance of an entire art-world, an entire visual culture. But most obviously it’s the disappearance of beauty. I think that it’s a mistake to think that we are somehow that separated from other creatures. Where am I going with this? There was a book that was written by this guy David Rothenberg, and it’s called Survival of the Beautiful. And today, in our world, it is really the beautiful things that survive, or survival of the interesting.

EF: Like the charismatic megafauna.

KF: Yes!

EF: That people are compelled to save animals that they find cute or beautiful.

KF: The polar bear.

EF: Or the panda bear.

KF: Jon Mooallem wrote that in his book Wild Ones — a sort of cultural history of wild animals in America — that when looking into the future of evolution, survival is going to have less to do with Darwin and more to do with [P. T.] Barnum.

EF: Oh…

KF: I think we want to be entertained, we want to be pleased. That’s why we keep fish in tanks and birds in cages. But maybe there’s a possibility for a new paradigm. Instead of captivity or wilderness, maybe there’s something in between. Do you know that every zoo has a Species Survival Plan for their endangered animals? So there’s a committee that meets, and they have all of the genetic information about every captive animal in a specific species, and they figure out which pairs should mate together in captive populations in order to create the largest amount of diversity. So in a way, we’re trying to freeze these animals in time. We’re trying to work against evolution, in a way. And then on the other hand we’re making wolves into pocket poodles.

EF: So it’s going in both directions?

KF: It’s going in both directions, but in both ways we’re very motivated by beauty. You know, dog shows and visits to the zoo are not that dissimilar.

EF: Could you talk about your use of taxidermy as part of the presentation but also as a way to think through something like morphology?

KF: Oh, taxidermy! What an amazing education tool. Today there is a mystique surrounding taxidermy, but essentially for designers, scientists, engineers, artists, or anyone working in biology, taxidermy has the educational capacity that taking apart a car and putting it back together will give you. Except in this case there is no original designer — animals evolved. It’s quite hard to believe when you start looking at animals very closely that such perfection could just “emerge” through biology. This gets even more pronounced as you carefully examine the way that animals are assembled and put together. They are unique, each is a one-off, bespoke, and custom design. For me there is no human-made design object that can equal this level of perfection. These creatures have been undergoing an iterative and dynamic design process between their form, function, and environment for millions of years. The more types of animals and variety of species you practice taxidermy with, the more something like morphology begins to create a sort of sublime understanding of form. It is quickest and easiest to see when practicing with birds. A bird of prey has very specific features that enable it to move and behave in ways that a pigeon never could. Just like industrial design reveals our human behaviors and motivations, studying animal form can reveal a world of information about how that animal lives and functions. Each specimen is a window into understanding a comprehensive design solution. In terms of materiality, this is incredibly important. Materials are not extrinsic choices — they are critical elements to any design and should be fully integrated into an overall purpose. I wouldn’t use wood in a chair unless there was a reason for me that required its particular properties. In the Endless Form/Endless Species project, I felt that I needed to use natural, biological materials to convey the beauty and complexity of nature’s designs. This led me to taxidermy and scientific model-making as a medium. The incredible level of detail that exists in animals is present at every scale — from the macro all the way to micro scales. This was important for me because I wanted people to be able to get up close to these prototypes and be convinced. I wanted to be able to make representations of biology and science to seamlessly blur into fiction and speculation. Honestly, by using taxidermy, I had to do much less work — nature had done so much already.

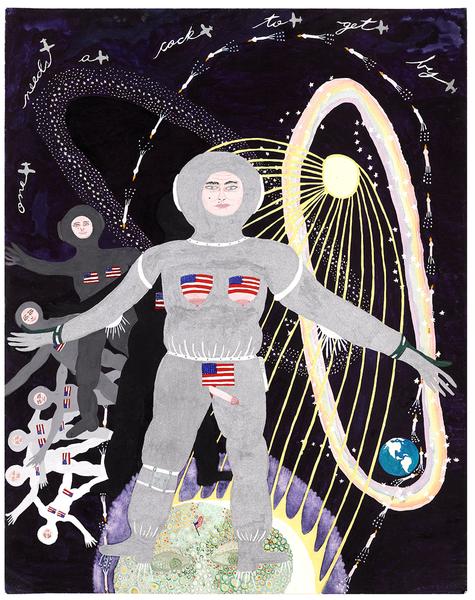

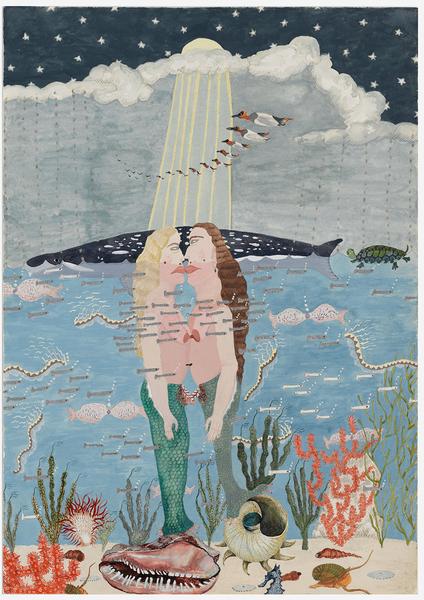

Evolved through a combination of artificial selection and synthetic biology, the three breeds in Fleming’s Endless Form/Endless Species marry speculative morphogenesis with human imagination. The Superbivore’s adaptations include extravagant cranial appendages, a long prehensile tongue, and dexterous cloven hooves.

Fleming’s process combines taxidermy and scientific model-making.

The Retro Reflective Carnivore’s adaptations make it a cunning predator.

EF: Do you ever sell your work? Your preparatory sketches and notes? Do you think of drawing as an important part of your process?

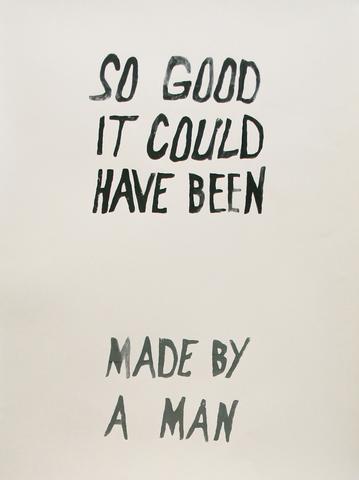

KF: I have not had a great deal of interest from people wanting to buy my work. I think that it is hard to classify it as “Art” or as “Design” and so people may not be sure how to approach it as either. Still, I would love to think that someone would find what I did enjoyable enough to want to see it every day and experience it as an “Art” or “Design” object. Or better yet would be if someone wanted me to design and build a custom species for them. That would be a dream project. It would be so fun to work with clients through the design process. Also, I would be fascinated to know what animals live in other people’s imaginations.

But, going back to the process, I do create a lot of preparatory sketches, photoshop mockups, and small maquettes to work through my ideas and flush out the shapes and forms. I also need to do a lot of material experiments before I start work on the final piece. My skill as a taxidermist and model-maker is really to know the constraints of each material well enough that I can anticipate what will work and what won’t — how far I can push the design and have it remain convincing. In that way it is not so dissimilar from my previous work as a furniture and footwear designer; I’ve always felt that having a hands-on approach is necessary to do any type of physical design.

EF: Okay, last question. What’s next for you? Any chance we can get you to relocate to Seattle and start that museum of recently evolved species you mentioned before?

KF: Yes! I would love to head out west and work on a “Post-Natural History” Museum! That would be amazing! Currently I have some shows coming up — one is on the West Coast — so that is exciting. Otherwise, I have been doing some work at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in Washington, D.C., in the Entomology Department. Insects are so incredible! I think more and more I can see the value in incorporating artistic and design processes within scientific disciplines. Both types of thinking — artistic and scientific — can really enhance and complement the other. I would love to teach workshops that help reconnect the arts and sciences, especially taxidermy workshops for designers, artists, and scientists. In the meantime, I have been looking at ways that my skills could apply to the commercial design world. I think there is a lot of possibility to alter our perception of nature and influence our relationships to other forms of life through the way we make and design products.

Overall, I hope I can continue to create experiences — in any number of forms — that inspire people to imagine new possibilities. We all get bogged down in certain ways of thinking, and I think we need to be reminded that technology is not deterministic, it is actually the exact opposite, and that’s really exciting!

EF: Thank you so much, Katie!

KF: My pleasure.