Rumi Koshino | Red and Blue

Essay by Colter Jacobsen | Photographs by Maggie Carson Romano

Drawing and painting can be a very intimate thing. I found myself thinking this at a recent music show where the artist Rumi Koshino was projecting a collaborative video accompanying live music. A video camera had been set up to record in real-time Rumi’s watercolor composition while she painted slowly and deliberately. The live-feed was projected behind the musicians onto an accordion-like backdrop reminiscent of a Japanese screen.

There was something absolutely hypnotic about watching one color run into another. A red brush stroke slides across the paper, meeting a blue brush stroke. The two rivers collide in cataclysmic purple. It’s a gesture made by an artist but nature takes over in the wake. The surface of paper becomes a floodplain where the edges of least resistance burst into expanding rivulets.

I noticed that Rumi seemed unconcerned with the final outcome of the image: she used liberal amounts of water. Her marks felt close to music, a present-tense gesture/mark of the moment. I read into the two colliding colors as human relationships. I fell in love with a brush mark that was suddenly obliterated by a grey pool…jolted by the fleeting moment of it.

How quickly we, as viewers, read into the marks and movement. Every mark is a decision, every nuance is connected to a brain synapse. And it’s this exchange, from the artist’s synapse onto a picture-plain to our receiving synapse, which is so mysterious. What is it about our human nature that projects narrative and emotions from simple colors, shapes and lines? I am reminded of the poet Philip Whalen describing his own poetry as “a picture or a graph of a mind moving, which is a world body being here and now which is history…and you.” The dual projections of sending forth and receiving go back even earlier than shadows bouncing on Plato’s cave.

The word project comes from the Latin, projectum from the Latin verb proicere “before an action” while projection (mid 16th century) has the same Latin root as project, yet it’s meaning is to “throw forth.”

I think of the tapa cloth drawings by women of the Maisin tribe of Papua New Guinea. They don’t have a word for art, per se. The closest word they have is Saraman, meaning “think & do.”

Rumi recently completed a project that consisted of making one drawing per day for 100 consecutive days. In a Facebook post, she stated, “I started my first 100-day (sculpture) project on this day, February 18th, 2015, prompted by Debra Baxter. Somehow, it feels perfect to finish my second 100-day (drawing) project on the same day, a year later, completing a circle.”

From such an approach, certain qualities tend to come to the forefront: looseness, lightness, quickness (see the first essay in Italo Calvino’s Six Memos for a Next Millennium). A daily practice also keeps your chops up.

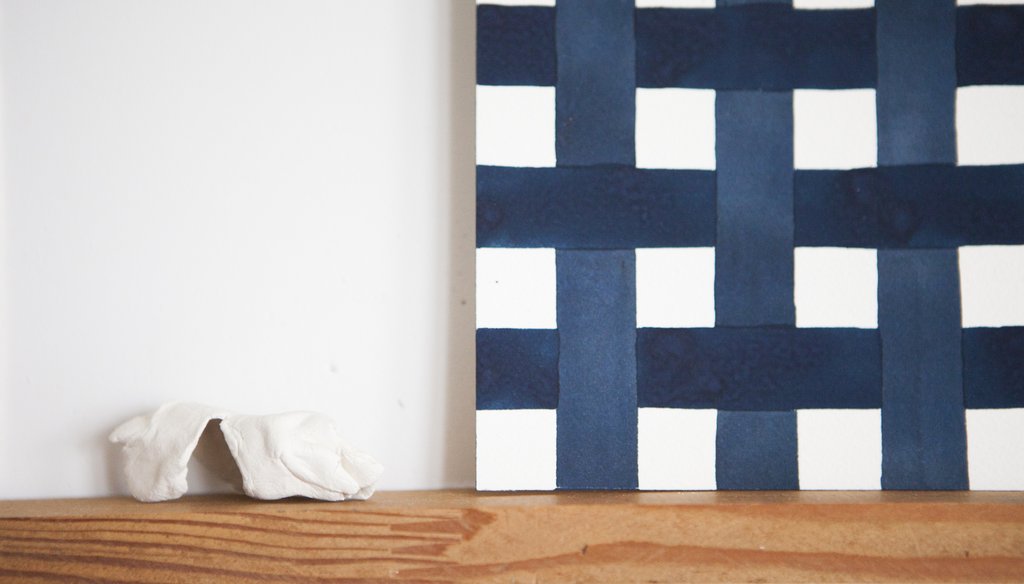

Rumi has lived in San Francisco for about two years. She moved from having a large live-work space all to herself in Seattle to a flat in San Francisco with three roommates. She has a small room and one closet. All this to say that she has substantially downsized. There is a new economy to her drawings. The word economy comes from the Greek, meaning “household management.” Can this system of daily drawing be a way to keep order in her household, and for her general mental stability? Even with such a small amount of space, her room still feels sparse. Only a few of her 100 drawings are displayed at one time. All of her “sculptures,” most of which were collapsible and made of paper, are tucked away somewhere.

Through the 20-something years that I’ve know Rumi, I’ve seen her work morph into all kinds of different sizes, shapes and themes. But even small, the scale can feel gigantic.

I remember the earliest works I saw of Rumi’s depicted very basic things: toes of a foot, a light switch, a house or I should say a home. Dwelling on the theme of home certainly made a lot of sense seeing that she had just left Japan to study in the U.S.

One particular painting I recall was a line of various colors in the shape of a rectangle that ran along the border of a rectangular white canvas. She said the line represented a road trip she had taken and each color represented a part of the trip. This road trip still lingers in my mind as a wonderful alternative to mapping time and space. I see it again in several of her 100 drawings.

Later came ladders and then bridges, many bridges, broken bridges, bridges that led from nowhere to nowhere, emerging out of an ocean, taking the viewer from one area of water to another area of water. The bridges of two cultures seemed the obvious metaphor though the more she built them, the more I think they actually were about the bridges of relationships, the bridges between any two people, no matter their culture, trying to communicate with each other.

The bridges eventually disappeared as if completely consumed by the ocean. And only the marks of water remained, vast oceans of marks. For her final show in Seattle she invited friends over to cut out envelopes from a very large-scale drawing of an ocean surface. The envelope, as an abstract bridge of distance, from a here to a there, is also a gesture of giving that, in turn, implies a return.

She can effortlessly alternate between abstraction and representation, the two often in dialogue with each other. This can also be said of her 2-dimensional work and her sculptural work. Both point back at each other. A drawing seems to play with being 3-D while a sculpture flirts with 2-Dimensions.

Since moving to the Bay, Rumi has been a little more light and playful. She tends to absorb her surroundings. Her skin membrane is porous. Patterns from her environs find their way into her drawings while strange interior, cellular-like shapes float in to disrupt the patterns. The ocean is still hanging out too, sometimes in the shape of drapes while clouds float through doors. And triangles continue to hint at envelopes, circles designate absence or eyes while pairs and symmetry are never too far off…

When I first met Rumi in a Color/Light/and Theory class, I remember looking at an art work with her. In the composition were two squares, one blue, the other red. We were casually talking about the piece when she pointed to the blue square and said “red.” It

was her first year in the States and I assumed that she was still acquiring her English skills. So I corrected her and said “blue.” She shook her head and again said “red.” About to repeat my blue, I took a look at her straight face. It finally eased into a smile and again, she said “red.” She was playing with me. Not only were her English skills advanced, but she was turning the world on its head.

Back to In the Studio