Gretchen Frances Bennett | To catch something moving, And make it still

Essay by Aidan Fitzgerald | Photographs by Andrew Waits

Gretchen Bennett’s drawings are dense collections of marks, pulling from all colors of a neutral palette. From far away, her drawings emit a low hum, as if she’s caught static energy on paper, the greyness of a screen with the brightness turned all the way down, low contrast, eyes half open. From up close, one realizes that the marks that make up the piece are vibrant and uniform. They are the work of someone concentrating more on the nature of mark making than on the purpose of the marks themselves. As she explained in her lecture to Evergreen College last year, “Drawing with deliberate attention given to the mark is critical to this process. Through drawing, I want to show my thinking.” She continues, “These works first appear to be photorealist colored pencil renderings, but the second read shows that they are actually interventions between daily moments and gestures, and everyday life experiences.”

Bennett works from photos and digital stills, usually from television shows, movies, or home videos. Her work asks a fundamental question of identity: how do we relate to those on the screen? How do we relate to others through time, through space, across distances?

Her body of work titled “The Killing” was inspired by stills from the television show of the same name. She saw herself reflected in the character, in the solitary exploration and investigation of the harshly beautiful Pacific Northwest landscape. Her work since then has reversed tack: “I used to take popular cultural references in order to understand the personal, and now I’ve flipped it, where now I’m taking the personal to join in a larger conversation, to understand a broader view, and since I do want it to be a conversation, that’s where I want people to resonate. I think it’s really important for me to remember that I am empathic, and I am empathic in the way that I feel experience and that’s how I place myself.” Her piece in the Vignettes collection, “Untitled (after Bruce Nauman)” is one such piece. It is a drawing from a still of a home video taken of Bennett while she was immobilized in bed after an injury. Bennett made the piece as homage to Nauman, another artist who deeply examined the body, everyday life, and physical actions in his work. And while the piece may be a nod to a conceptual artist, it is rooted in the process of drawing: the palette stretches to all colors, but the values are consistent. Each object and detail is perfectly rendered, but not so perfectly described so as to become the focus of the piece. Bennett is recording the pattern of light in the image, and not concentrating on her own image reflected back at her. She’s concentrating on relaying the information of the moment, not her own memory. She’s allowing us into her personal moment, filtered through the lens of 20th century conceptual art, the long tradition of self-portraiture, and the expectations of the female body in art.

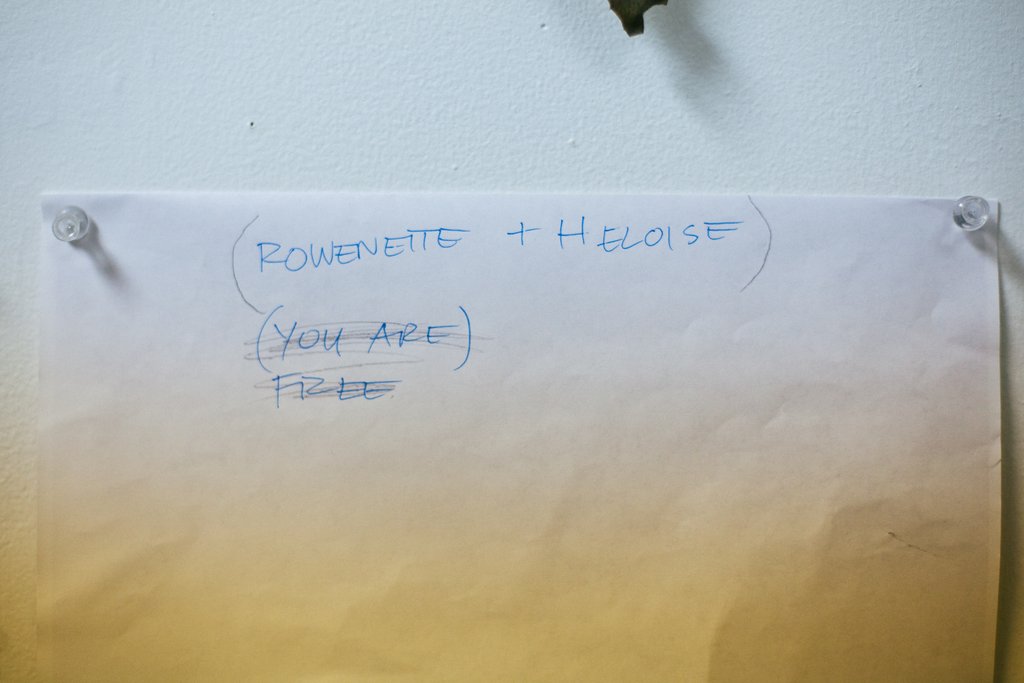

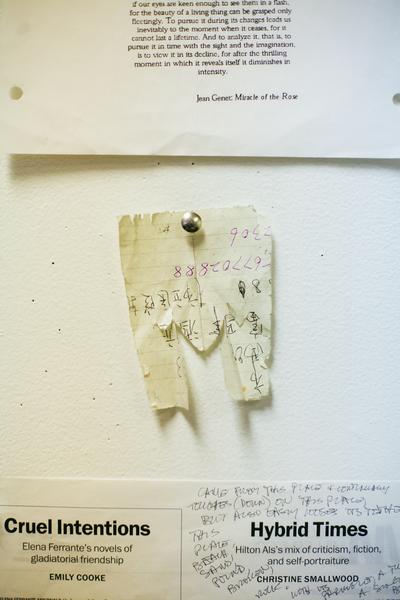

This kind of conversation with the world through art is a strong through-line in Bennett’s recent work. She has long been an artist without a defined medium, and lately she has been incorporating her writing, found objects, and sculpture into her studio practice. In one body of work, entitled “M Diary,” she enters into a conversation with herself, following the structure and tone of Roland Barthe’s Mourning Diary and Lover’s Discourse. “I treat the drawings and the writing both as textual entries, they’re both diaristic, and that said, I think they are both abstract enough that they become a space for other people to join in. I’m not pointing specifically to things and saying ‘you specifically look at this,’ but if I can abstract it enough and make it a neutral space, meaning my drawings and my writing together, then it’s abstract enough for other people to see whatever they see.”

I kept coming back to the idea of distance in Gretchen’s work. She distances herself from her own process of drawing by compartmentalizing sections of the drawing rather than approaching the drawing as a whole. “I want to catch something moving and make it still, filter that still so that it can move elsewhere, differently, giving a slow read. We make things iconic because we want to study and get caught up by something. We’re always as viewers and makers fixating and studying in order to close distance, to cross distance. This is pleasurable but futile, but it is a kind of movement, to try to bring something closer and make it iconic.”

Gretchen and I talked for over an hour, intermittently interrupted by the boisterous rattle of a work crew on the roof. Going over the interview, I began to notice new things about her words and her work. Transcription is a strange thing for me. How we take language and approximate it on the page, abstracting and distancing it from ourselves, but also laying words bare for others to interact with, magnifying certain points while glossing over others. Body language, setting, inflection, verbal tics—these are lost in the transcription process. In their place we are left with a record of thought and communication, and also concrete evidence that these ideas have been transmitted and are continuing to be transmitted (by way of someone reading over a transcription).

I mention this because as I was transcribing our interview, it dawned on me that this transcription process—the distancing of the artifact from the event it is recording—is central to Bennett’s work. She is examining pieces of her life up close, but presenting them in a drawing with a neutral tone, as objective fact, untainted by her own bias. There is no dramatic shading, no theatrical mark making. And in this way she allows us in to her life, but also encourages us to examine our own, to see our personal histories in hers. “In drawing, I think as I’m noticing something, I’m wanting to relay it. And so therefore my work is for me, but because I have the impulse to relay it, it’s for others. It’s me showing my thinking, and showing questions. It’s almost like in the moment that I receive the information, I’m transcribing. I’m recording out what I see.”

Back to In the Studio